Books

The Profound Lesson Helen Frankenthaler Learned About Painting From Visiting the Old Masters at the Prado

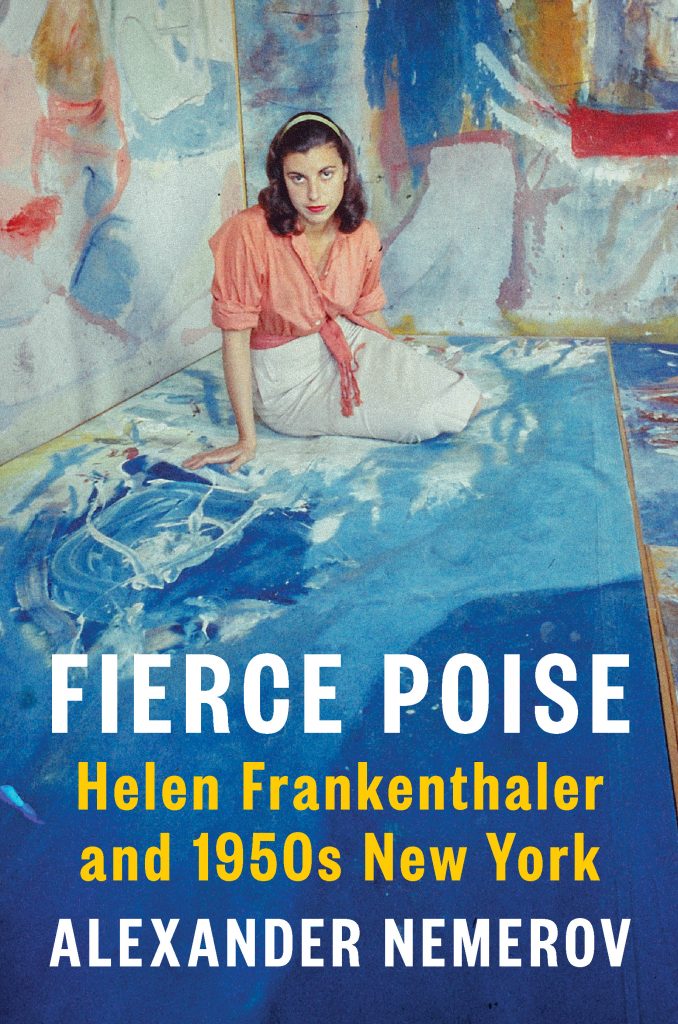

Read an excerpt from the new book "Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York."

Read an excerpt from the new book "Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York."

Alexander Nemerov

Helen sat on the steps of the Prado, smoking a cigarette in the blazing heat of midafternoon while the museum was closed for siesta. By then she had been in the darkened galleries for five hours, having arrived when the doors opened at nine, and she would go back in when the doors reopened and stay until closing time at 7:30. This was Helen’s routine every day during her time in Madrid, part of a two-month tour she took alone that summer through Spain and southern France.

That spring, Helen had been thinking of escaping Manhattan for part of the summer. The city was too grimy and noisy. Her analyst was taking the month of July off. Her sister Gloria was in Europe with her husband, ticking off boxes on the list of popular sites—“everything was wonderful, beautiful, divine, delicious”—and the banality of her sibling’s tourism was an inspiration: Helen knew she would never waste a European trip like that. Meanwhile her mother’s condition was worsening—“She is really a very sick, helpless, hopeless woman in so many ways, and the whole situation is depressing and difficult to manage”—and the relationship with Greenberg was never easy. On July 8, she was one of a thousand passengers on board the S.S. Constitution, an air-conditioned luxury ocean liner more than two football fields long, departing New York for the six-day voyage to Gibraltar.

[…]

Her visits to the Prado were a pilgrimage to stand before actual works, to bask in their aura. She did not care for a “museum without walls,” a phrase coined by French writer André Malraux in his book The Voices of Silence, published later in 1953, which extolled the fact that “an art student can examine color reproductions of most of the world’s great paintings” without ever leaving home. Helen was no longer an art student. Her Bennington days critiquing postcards on bulletin boards were over. She was a real painter now, with far more blood and toil and ego invested in the pursuit. She would look at the Old Masters to double down on her own art, to draw direct inspiration from the greatest artists who ever lived, to fashion an imaginary alliance with these men from the past who would inspire—by some internal standard of her own—the measure and seriousness of her art.

[…]

It all required a deep breath, taking in paintings of this kind, none more so than those of Peter Paul Rubens, an artist Helen loved whose work anticipates her own protean creative energy. Master of bombast and vulgarity, Rubens was probably the wettest painter who ever lived, the artist who most reveled in oil paint’s shimmer and viscosity, the one who put a person in mind not of a palette but of a bubbling cauldron as the source into which he dipped his brush. In picture after picture he set about his subjects—martyrs, mythologies, coronations—with a zeal that portrayed skin, water, sky, robes, fishes’ gills, decapitated heads, marble statues of maenads squirting fountain water from their breasts, muscles flexing on broad backs, the foliage of trees, anything at all, as if these lustrous facsimiles were nothing more than the products of a regular day at work, just another morning in the studio. Helen thought Rubens was “the greatest painter of all.”

Two years before her trip to Spain, she explained to [critic Sonya] Rudikoff the charge she got from looking at such paintings. The word was notably anti-intellectual; the more bookish Rudikoff did not like it. “Do you really get a ‘charge’ out of a painting?” she wrote back. Helen’s response was, “Of course I do! I believe that’s the only way to really look at a painting.” Sure, works of art offered more: “I do think that the first second of seeing a great painting is only a charge; and then you can look at the whys of it; its history or tradition, technique, etc.” But for Helen that first moment was paramount; a picture succeeded or failed exactly then, not by some academic scrutiny that came afterward. She was adamant that “no painting is good ‘intellectually.’” And she credited one person with helping her make that realization. Paul Feeley had taught her how to paint, Meyer Schapiro had taught her what paintings mean, but [Clement] Greenberg had “really helped me to see or feel paintings; to develop a finer eye and detect the truth and magic in paintings.” She had gone with him to Philadelphia in late March 1952 to see a touring show of Old Master paintings from Vienna and had come away with a “thrilling feeling.” Now, at the Prado, without Clem, Helen was finding this magic for herself, and she was thinking that she, too, must make knock-out paintings—works that would stun the viewer with an unforgettable first impression, a sensation that endured, a “charge.”

At stake was the greatest thing a painter could do—convey the sense of being alive at a certain time, just as the Old Masters had done in their eras. In New York Helen looked around and felt that few painters were doing that. “I feel that contemporary painting simply isn’t great painting,” she lamented in 1951. The art crowding the walls of modern art galleries “isn’t good enough for us, now.” It missed the feeling of life that Helen found at Ed Winston’s Tropical Bar and other such places: the texture of experience, the life on the street, the elusive and intoxicating sensations that Ralph Waldo Emerson back in the 19th century had extolled as the greatest subject for American poets and painters: “the meal in the firkin; the milk in the pan; the ballad in the street; the news of the boat; the glance of the eye; the form and gait of the body.” The Old Masters had found these sensations in their respective eras, portraying biblical and mythological events with a lustrous presentism: a peasant couple in their coarse rags welcoming disguised Jupiter and Mercury to their hut; callous soldiers in their leather jerkins and silvery black armor, rolling dice and swilling ale, one of them fitting Jesus with his crown of thorns. As she thought of painting in her own time in comparison, Helen went into a “real depression.” She had gone first to a contemporary art show at the Kootz Gallery in New York, then to a masterpieces show at a Manhattan Old Master gallery, then back to Kootz, where the new paintings that had looked fresh and exciting before now looked meager, unimportant, trivial. She made an analogy: “Shakespeare is greater than most (all) things going on now poetry-wise, but this is not his era.”

Who would be the Shakespeare of the 1950s? Who would be the Rubens? Pollock was on their level. So was Arshile Gorky, the morose Armenian hedonist whose surrealist-inspired paintings of lush Venus flytrap pleasure gardens, aglow in spike edges and orifices, had grown in fame since his suicide in 1948 at the age of 44. But Helen felt that they were “the only ones of a particular school that give me a real charge that might compare— somewhat—to the excitement I get from seeing a really great Old Master.”