Art & Exhibitions

A Landmark Show Puts Helen Frankenthaler’s Masterpieces in Dialogue With Pollock and Rothko

In the aptly titled "Painting Without Rules" at Palazzo Strozzi, the abstract expressionist's liberated and vivid canvases come together in the largest Italy-based retrospective to date.

On a warm Autumn evening, with the sun already setting and the moon beaming over the rusticated stone of Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, I walked through the fittingly elegant exhibition “Helen Frankenthaler: Painting Without Rules” (on view from September 27, 2024, through January 26, 2025). I couldn’t help but smile at the huddled group of exhibition invigilators engrossed in deep conversation, one gesticulating wildly, another throwing her head back with laughter. Their reciprocal joyfulness perfectly mirrored the mood of this show, which is all about friendship and the spirit of unity within these bonds.

The tour-de-force—though by no means a comprehensive retrospective—places select paintings and sculptures by Frankenthaler in dialogue with works by her close contemporaries. It is a well-versed art canon roll call that includes Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Anthony Caro, David Smith, Anne Truitt, and Robert Motherwell, who was Frankenthaler’s husband from 1958 through 1971. Curator Douglas Dreishpoon, director of the Catalogue Raisonné project at the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation in New York, envisioned this lens of friendship, saying it is “another way to see and contextualize Frankenthaler’s own innovations.” He emphasized that the artist “chose her inner circle carefully, and those fortunate enough to be included were nurtured, fêted, and sustained.”

Helen Frankenthaler: Painting Without Rules, Palazzo Strozzi, 2024. Photo OKNOstudio copyright 2024 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

While a standalone Frankenthaler show would surely have been as compelling, this is still the most extensive retrospective of the artist’s work in Italy to date. With minimal wall labels, viewers are free to become immersed in the full physicality of Frankenthaler’s works and draw their own connections between the artist and her friends—a generous curatorial strategy that stresses object over interpretation, aesthetics over discourse. And it works: you can lose yourself amid the expanses of color and form.

The Power of Color—and Pollock

Celebrated for her techniques of lightly soaking and staining canvases with solvent-diluted pigments, pouring out buckets of paint and moving it around with sponges or the edge of her hand, Frankenthaler believed that “scale and the play of space and light are largely what it’s all about.” Spilling, staining, tinting, and using color as line, the artist seemingly spread the edges of her painting, stretching the limits of the border while staying in and on the picture plane.

The exhibition, which is loosely chronological, opens with one of Frankenthaler’s most capacious works, Moveable Blue (1973). Here, her pigments feel alive, as if they are still spreading and eddying, fluid and free—a wide pool of aquamarine expands across the breadth of canvas, bleeding into mustard yellow and ochre to form rivulets of watery green. Opposite, the acrylic-on-paper drawing Fiesta (1973), minute by comparison, but no less sensual, uses brick-red paint so watery that Frankenthaler has traced it all the way around the rectangular sheet of parchment in one swoop, pigment becoming paler as it forms an amorphous shape that folds back in on itself; it consumes moments of pink and green, and is then sliced through with one line of brilliant yellow.

In an exhibition that draws strong parallels with Frankenthaler’s male contemporaries, one inescapable fault of the show is in the omission of more of her female counterparts: Frankenthaler was close with painter Grace Hartigan, for example, which is a glaring exclusion. Nevertheless, it’s hard not to feel tantalized by one of Frankenthaler’s early influences, Jackson Pollock; the artist first saw his radical black-and-white paintings the artist saw at Betty Parsons Gallery, and by which she was profoundly impacted. Pollock’s intuition for expansion and ode to drawing enabled Frankenthaler to assume an approach without limits. The rhythmic drawing and dripping of black enamel paint in Pollock’s Number 14 (1951) plays out across the surface plane: defined by an abstracted realism, his choreographed, dynamic gestures formulate lines and shapes that suggest symbols, hieroglyphics, and subliminal imagery. Placed next to this is Frankenthaler’s Open Wall (1953), in which layers of blue, pink, and yellow are punctuated with precise daubs of thick crimson. These resonate as bloodied, bodily interruptions in a painting that is ultimately about the relationship between space and form.

Helen Frankenthaler: Painting Without Rules, Palazzo Strozzi, 2024. Photo OKNOstudio copyright 2024 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Friendships and Influences

The pairing with Pollock sets the tone for an exhibition that delivers gallery after gallery of exquisite associations: from the layered clouds of color in Frankenthaler’s Tutti-Frutti (1966) installed behind the stacked beams of David Smith’s Untitled (Zig VI), steel girders hand-painted yellow and cut at varying widths that seemingly defy gravity, to the adjacent monolith of Anne Truitt’s Seed (1969), a sculpture of creamy acrylic on wood which seems to hover off the ground, playing with solidity vs. malleability, and perhaps even magic.

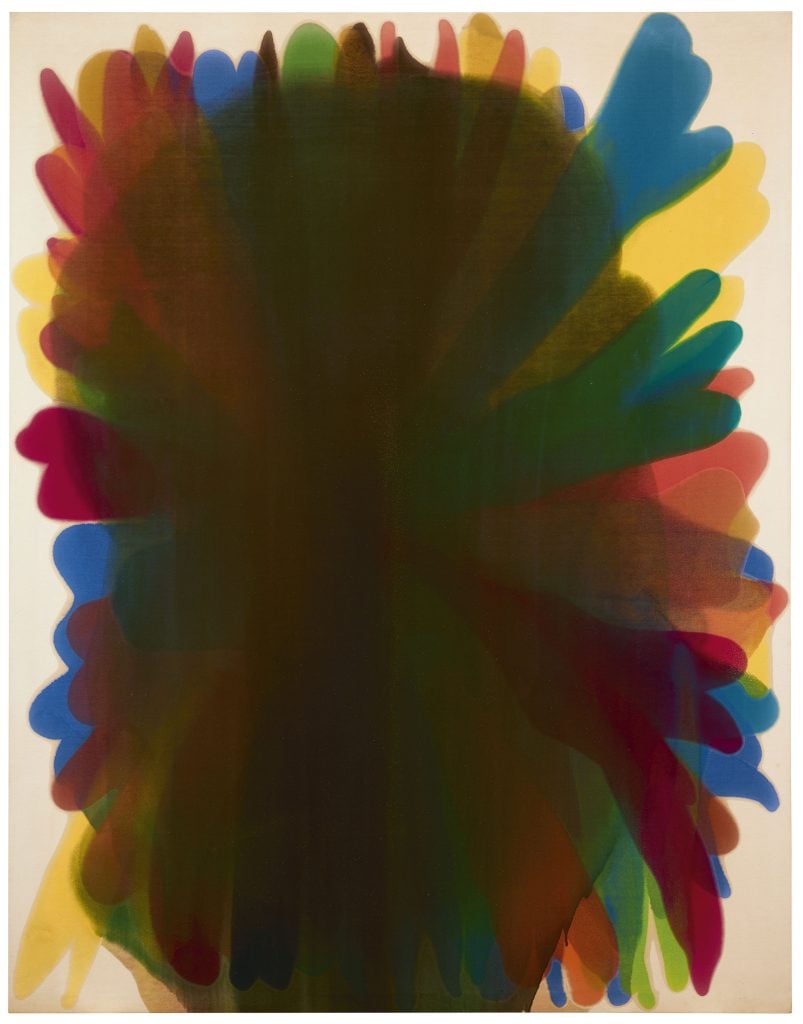

Frankenthaler influenced the likes of Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, who also feature in the exhibition. Both began experimenting with the soak-stain technique after the art critic Clement Greenberg (with whom Frankenthaler had a five-year long relationship) took them to her studio in 1953 while she wasn’t there. Louis, for one, always acknowledged his debt to and admiration for Frankenthaler. Here, his Aleph Series V (1960), which is part of the ‘Florals’ series, sees thinned acrylic resin paint poured in petal-like patterns that gush from the middle of the canvas out to the edges. Louis was admired for liberating color from the limits of drawn boundaries, and in this work, the bright tones of red, blue, yellow, green, and orange are so copious as to have mixed on the surface into a brownish area that spreads over the radiant ribbons of color as a strangely enticing muddied veil that you long to peer behind.

Morris Louis Aleph Series V 1960. New York, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation © Maryland College Institute of Art (MICA) / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

A standout moment is the chapel-like staging of Smith’s steel-and-bronze sculpture Portrait of the Eagle’s Keeper (1948–49)—one of Frankenthaler’s first acquisitions from Smith, her dearest friend. The androgynous alien-like creature, with breasts and antennae and holes and protrusions, is presented against a giant facsimile of Frankenthaler and Motherwell’s East 94th Street townhouse living room, where this sculpture once lived. It’s an interior that dreams are made of: to the left of the fireplace is Frankenthaler’s Mountains and Sea (1952), her breakthrough work with the soak-stain technique; to the right is Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 70 (1961), his emotionally-charged, rough black ovals acting as a lamentation after the Spanish Civil War; and above is Rothko’s Untitled (1949), a gift from the artist in which a pale grey mass drifts in-between heaven-and-earth like bands of lemon yellow, all humming within an atmosphere of mahogany.

In the early 1960s, Rothko was to Frankenthaler what Pollock was to her in the 1950s; his approach to shapes as performative portals of hovering light influenced her own sense of drama. A frontrunner in the show is another of his Untitled paintings from 1949, in which hazy planes of red, yellow, green, and brown float atop one another in a universe all of their own. This effect can still be felt in Frankenthaler’s dazzling canvases from the 1980s, like Easter Light (1982), its aqueous washes of purple bleeding into hazy pillared planes of black, interspersed with thick smears of shocking white.

Helen Frankenthaler Ocean Drive West #1 (1974). New York, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation. © 2024 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Explorations of Form

“Painting Without Rules” could have benefitted from one room dedicated to the steel sculptures that Frankenthaler made in her friend Anthony Caro’s London-based studio in 1972; three of these (Matisse Table, Yard, and Heart of London Map) are spread throughout the show, yet their direct grouping would have emphasized not only Frankenthaler’s skillful exploration of line and form in three-dimensional space, but also the evocative interplay of mass, volume, and weight between these works.

Frankenthaler’s later and lesser-known paintings are also decidedly sculptural and comprise lively reliefs of paint that are sometimes layered thickly and vigorously handled. Maelstrom (1992), for example, is characterized by its frenzied and worked surfaces of white, yellow, and green, which use gel medium mixed with acrylic to create texture. At this time, the artist used tools like rakes and mason trowels to create choreographed compositions, and yet these canvases lack the graceful elusiveness and subtlety of her soak-stain technique. Nonetheless, it is perhaps the sense of the artist’s own touch, of her physicality embedded within these works that instills a dynamic energy and vitality that repeatedly pulls your eye around the canvases and into the depth of their details.

Helen Frankenthaler Heart of London Map (1972). The Levett Collection, inv. CL 1026 © 2024 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The acrylic-on-canvas painting Driving East (2002) ends the exhibition on more-or-less a perfect note: an atmospheric abstract in which the deepest of greens and the moodiest of greys meet at a horizon line. The paint is thinned out, washy but somehow dense and rich. A sliver of pale blue sparks a moment of light. Either the day is darkening, or night is giving way to sunlight at dawn. It is indeterminate and indefinite; a seemingly endless plane through with your eyes keep on drifting; a landscape that you could drive along forever, with Frankenthaler beside you at the wheel.