Pop Culture

We Did an Art Historical Analysis of Halsey’s Cryptic 13-Minute Metropolitan Museum of Art Video. Here’s What We Discovered

The artist released the video as a way to unveil the cover art for her new album

The artist released the video as a way to unveil the cover art for her new album

Katie White

Last week, pop singer Halsey revealed the artwork for her new album If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power in a 13-minute video set in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The video shows the 26-year-old singer, who is expecting a child with boyfriend screenwriter Alev Aydin, walking through the museum’s European art galleries clad in a silver bodysuit and ochre veil.

Throughout the video, she pauses to observe various paintings, primarily of the Virgin Mary. Aside from the singer, the galleries appear empty and the only soundtrack is the ambient noise of the singer moving through the museum.

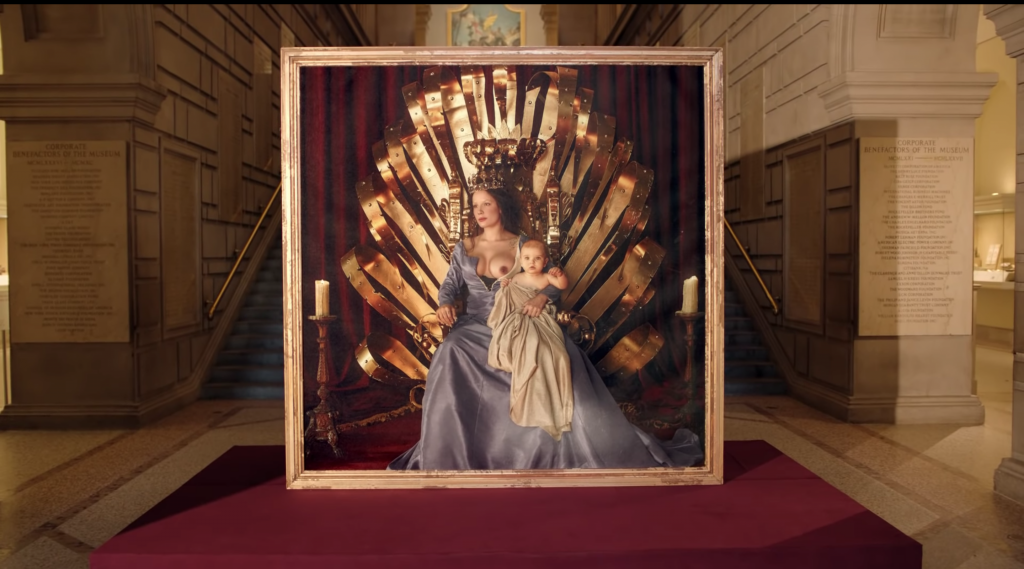

At the end, she appears at the base of the museum’s main staircase, where she pulls back red drapery to unveil a monumentally scaled photograph of the herself by photographer Lucas Garrido. The photograph captures Halsey seated on a golden throne, wearing a blue dress and elaborate crown. One of her breasts is bared, and an infant (not her own) is seated on her knee.

The image is, of course, sharply reminiscent of the depictions of the Virgin Mary we’ve just observed in the museum halls.

In an Instagram post, the singer explained that her fourth studio album, produced by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, is “a concept album about the joys and horrors of pregnancy and childbirth.”

“It was very important to me that the cover art conveyed the sentiment of my journey over the past few months. The dichotomy of the Madonna and the Whore,” she wrote. “This cover image celebrates pregnant and postpartum bodies as something beautiful, to be admired. We have a long way to go with eradicating the social stigma around bodies & breastfeeding.”

Halsey is not the first musician to feature artwork, or even a museum, in a video. In January of this year, FKA Twigs debuted “Don’t Judge Me,” which prominently featured Kara Walker’s sculptural fountain Fons Americanus, on view at Tate Modern in London. And most famously, Beyoncé and Jay-Z filmed their 2018 music video, “Apeshit,” at the Louvre in front of (among other works) the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo (the video was credited with a surge in museum attendance, too).

Still, Halsey’s video is unique in that its focus is primarily on the artworks—not as a backdrop to her own musical performance. The strangeness of the video had us wondering what it all means.

We’ve pinned down some art-historical observations that may help you better understand what Halsey is after.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna and Child (ca. 1290–1300)

Throughout Christian history, theologians have debated the dual human and divine natures of the Virgin, and artworks have often reflected these shifting understandings.

As early as the second century, the Virgin Mary was described as a so-called “second Eve” who, through the acceptance of her anointed role as Mother of God, served to balance Eve’s original sin in the Garden of Eden.

While it might be simplistic to proffer Mary as “Madonna” in opposition to Eve as “whore,” these tensions have been battled out by theologians for centuries, with debates over her sinlessness, her virginity, and her regeneration as a form of idolatry shifting over time.

During the 12th and 13th centuries (and inspired largely by the writings of theologians such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux), the Virgin Mary began to be perceived as an approachable intercessor between sinful humanity and a just God, resulting in a glut of Marian imagery that endured into the Renaissance (the proliferation of “Notre Dames” is a testament to this period known as the Cult of the Virgin).

Halsey stops to observe several Medieval and Renaissance works that capture this dichotomy of the Virgin’s motherly and also ethereal qualities. Most notable is Duccio di Buoninsegna’s Madonna and Child (ca. 1290–1300), a masterpiece of early Renaissance art that transitions the Virgin from a static, untouchable icon into an emotive figure—what Met curator Keith Christiansen has described as her new “human dimension.”

Duccio imbues the work with her newfound humanity by emphasizing the dimensionality of her figure and the sorrow of her face, tying her body to the corporeal realm.

Giovanni di Paolo, Madonna and Child with Saints (1454). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The image captures what Halsey aims to depict in herself. “Me as a sexual being and my body as a vessel and gift to my child are two concepts that can co-exist peacefully and powerfully,” she wrote in her Instagram post.

Other artworks in the video similarly evoke these tensions between the divine and human. In Luca Della Robbia’s Madonna and Child with Scroll (ca. 1455), the artist tenderly depicts the Virgin and Child but uses terracotta glazed in white to hearken back to classical antiquity and an otherworldly “out of reach” realm.

Similarly, Giovanni Bellini’s Madonna and Child (late 1480s) draws back the “cloth of honor”—the material often draped behind the Virgin and Child in paintings—to reveal a landscape caught between winter and spring, an earthly metaphor for death and resurrection.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Esther before Ahasuerus (1628-30). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gallery 621.

Two of the images Halsey pauses before are not depictions of the Virgin Mary, and both are worth noting.

One is Guido Reni’s Charity, which shows a woman breastfeeding with three children in an ancient symbol of the virtue. The other is Artemisia Gentileschi’s Esther before Ahasuerus, one of the 17th-century artist’s most ambitious paintings.

Here, Gentileschi shows the Jewish heroine Esther having fainted after entreating her husband, King Ahasuerus of Persia, to stave off the massacre of the Jewish people, a gesture that would put her at risk of death. Esther’s petitioning on the part of the Jewish people has sometimes been interpreted as an Old Testament precursor to Mary’s intercession on behalf of humankind before God.

What’s interesting here is that rather than depict a historical event, Gentileschi has transformed the biblical narrative into one of contemporary theater, with a dramatic light cast on Esther, who wears an elegant 17th-century dress. In this way, Halsey interjects herself in Gentileschi’s lineage of bringing historical heroines into the contemporary moment through a process of artistic creation.

The album art for “If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power” showing the 26-year-old singer as an enthroned Madonna and Child.

At end of the video, Halsey appears at the base of the Met’s main staircase and pulls down a red velvet mantle to reveal her new album cover.

The Lucas Garrido photograph makes strong reference to one of art history’s most memorable images: The Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels from the Melun Diptych by the French court painter Jean Fouquet.

In this strange image, the Madonna is depicted on an elaborate gold throne, wearing an intricate crown and a blue dress. One breast is bared and the Christ-child is shown on her knee.

This image, which isn’t in the collection of the Met but rather the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, is a particular conflation of the “Madonna and whore” dynamic Halsey mentions in her Instagram post.

The Virgin in this image is believed to be a disguised portrait of Agnès Sorel, the mistress of King Charles VII, who was considered one of the most beautiful women of her age.

Jean Fouquet, Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels (right wing of the diptych) also known as the Melun Diptych. Courtesy of Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

The iconography of the image is important to understanding Halsey’s album cover as well.

This image is known as a virgo lactans—a breastfeeding depiction of the Madonna. In the 12th century, virgo lactans became popular amid the surge in Marian imagery; the milk of the Virgin was often interpreted as the life-giving precursor to Christ’s blood, which grants eternal life.

Such images, painted at a time when most wealthy women hired wet nurses, aligned the Virgin to more common women. Such imagery fell out of favor, however, in the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and the Council of Trent on the grounds of propriety—a shift whose repercussions still exist to this day.

In this way, Halsey’s own bare-breasted image recalls earlier exaltations of “pregnant and postpartum bodies as something beautiful, to be admired” in her attempt at, as she put it, “eradicating the social stigma around bodies & breastfeeding.”