On View

Is That a Dead Body? 8 Breathtakingly Odd Works in the Met Breuer’s Unconventional Survey of Figurative Sculpture

From a mummified philosopher to a philosophizing robot, there's a lot to see here in "Like Life."

From a mummified philosopher to a philosophizing robot, there's a lot to see here in "Like Life."

Taylor Dafoe

Get ready to be creeped out. This week marks the two-year anniversary of the Met Breuer’s opening, and to celebrate, the museum is launching what is perhaps its biggest, most ambitious exhibition since its inaugural show, “Unfinished.” Dubbed “Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300–Now),” the new show brings together 700 years worth of sculptures, from 14th-century Europe to today, that have sought not just to represent the human body through art, but to push that representation through to the uncanny.

Curated by Luke Syson and Sheena Wagstaff, the exhibition features 120 works—a selection, they say, narrowed down from over 900 objects—and appears to have ambitions to please both academics and selfie-prone tourists. While the working title was “Polychrome,” and the show, according to Syson, “began as a rather orthodox plod” looking at the history of the European tradition of colored sculpture, it evolved into something quite a bit less history-bound and quite a bit weirder. Its final vibe is that of a rather stately cabinet of curiosities, mixing dignified art historical touchstones with the macabre and the odd.

Given its scope, there’s bound to be a little something for everyone. Here’s a list of a few of the highlights that await in “Like Life”:

Donatello, Bust of Niccolò da Uzzano (1430s). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

On loan from the Museo Nationale del Bargello in Florence, the proud intensity of this posthumous likeness of a powerful Florentine justice minister conveys all the heroic naturalism that made Donatello famous—with the peachy polychrome terracotta of his flesh adding extra oomph. Some admirers have found the “life-like” coloring to distract Donatello’s masterly sculptural technique—but the uncanny effect has also always made it a crowd favorite.

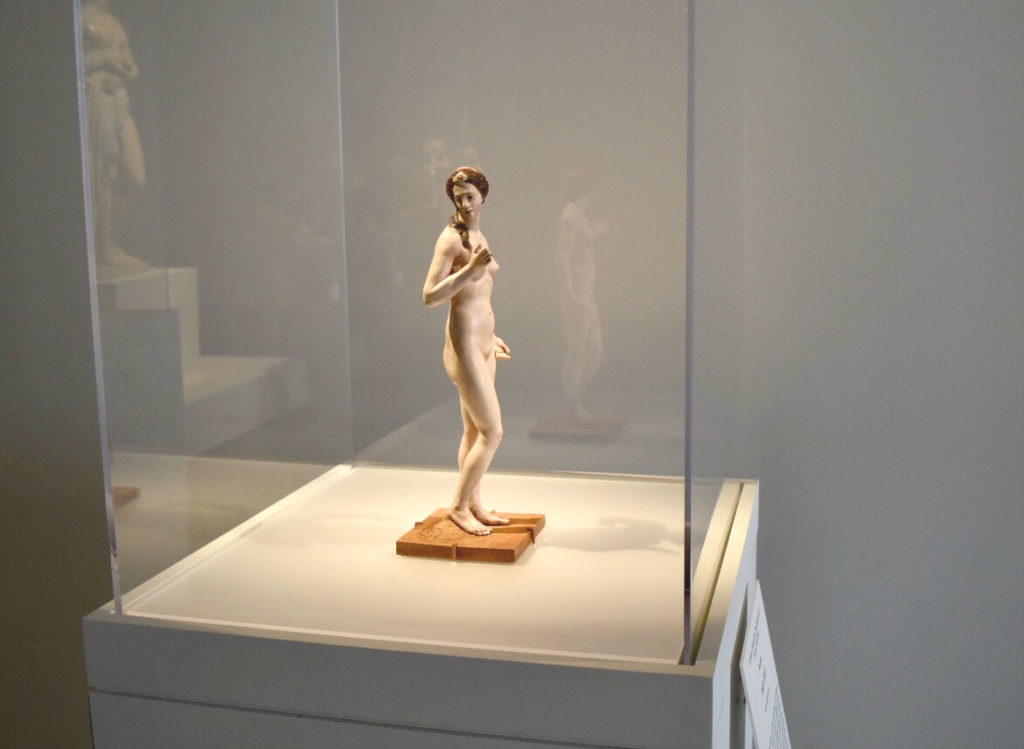

El Greco, Pandora (1600-1610). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

This is among the smaller works in “Like Life,” actually little more than a figurine. The moment it captures might almost represent mythic Pandora looking over in curiosity at her famous box (actually it was a jar), and thinking to herself, “Should I? Well, why not?” As opposed to the eerie unreality of the Mannerist master’s famous paintings, this wooden sculpture is notable for its eerie reality, from her flushed cheeks to the ripple of a vein in her arm to painted-on wisps of pubic hair. It’s meant to be a pair with another figure, Epimeteo, representing Pandora’s husband—but he has stayed behind at the Prado in Madrid.

This mechanized wax sculpture, on loan from Madame Tussauds in London, features a sleeping beauty figure—a popular depiction of cataleptic women at fairground entertainments in the 18th century—whose diaphragm rises and falls slowly, as if she were truly animated by breath. This particular sculpture is a recreation of a work first made in 1765 by Swiss wax modeler, Philippe Curtius (1737–1794)—the uncle of Marie Tussaud who taught her the art of making wax figures. The pale, blonde woman was based off the likeness of Madame du Barry, Louis XV’s infamous mistress who was eventually jailed and beheaded for treason during the French Revolution.

Thomas Southwood Smith and Jacques Talrich, Auto-Icon of Jeremy Bentham (1832). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The ghoulish highlight of “Like Life” is also a testament to the delirium of reason: Jeremy Bentham’s preserved corpse. The Utilitarian philosopher was so rational-minded that he believed that ethics could be reduced to a mathematical problem, the “felicific calculus”; his mummification as an “auto-icon” was a statement for the ages that he neither believed in nor respected superstition, and the figure has presided as a reminder of Bentham’s influence at University College, London since, the institution which sent it to New York for the show. Is it symbolic that the creepy “auto-icon” later literally lost its head? Bentham’s head had to be replaced, so what you have here is a clothed skeleton topped by a wax face as a symbol of hard-nosed Anglo-Enlightenment rationalism, a manifesto piece for this show about the so-real-it’s-surreal.

Marc Quinn, Self (1991). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Aside from Damien Hirst’s shark and Tracey Emin’s bed, this is one of the more famous statements of Young British Art, if only for the freak factor: It’s a life-sized cast of Quinn’s own face, made of some eight pints of his own blood, frozen. The version in “Life Like” is cradled in a refrigerated glass case that occasionally hums to life to preserve the perfect temperature for the blood-ice sculpture. As Elizabeth Fullerton noted recently in ARTnews, Quinn has made a new version of Self every five years—but this, the original, from 1991, actually looks the most elderly. So maybe the bleeding process is working to keep the guy young.

Janine Antoni, Saddle (2000). Courtesy of the Met Breuer.

Janine Antoni’s evocative sculpture Saddle doesn’t actually feature a figurative body; instead, it merely implies the presence of one. Antoni cast hardened rawhide over her own frame while she crouched on hands and knees. The freestanding sculpture depicts the outline of her body, but the interior of the work is hollow. The name of the piece and the use of animal hide suggests a dehumanizing act, as if she had been mounted like a horse. But the rumpled surface and hollowness underneath invites other possibilities, a person in hiding, perhaps, or enshrouded before burial.

Paul McCarthy, Paul Dreaming, Vertical, Horizontal (2005-12). Courtesy of the Met Breuer.

In an exhibition of works pushing the uncanny, Paul McCarthy’s silicone cast of his own person feels most realistic—so much so, in fact, that one is almost wary in getting close to it, afraid that the figure could open its eyes at any moment. McCarthy first created the self-portrait in 2005, intending for it to serve as a prop for a film. However, he ultimately decided to present the sculpture as a work unto itself, posing the pants-less figure prostrate on a cheap lawn chair. Many of McCarthy’s works tap into the absurd, the gross, or the just plain weird, but Paul Dreaming, in its exacting replication of the 60-year-old artist’s body, reads as a portrait of a man reconciling himself with the decay of his body, and confronting his own mortality.

Goshka Macuga, To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll (2016). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

A showstopper and part of a growing contemporary fascination with spooky robots, Macuga’s bearded android-philosopher holds court in the agora of the gallery, engaging its audience in a series of ruminations about the meaning of life, its jerky movement moving in and out of being convincingly human. The figure’s sonorous lecture is convincingly profound, though it is strung together from a tissue of quotes, from Walter Benjamin to Ayn Rand. Like life, it’s super strange.