People

‘She’s Kind of Our David Hockney’: How Hilary Pecis Set the Art World Aflutter With Charming Paintings of Life in Los Angeles

With a sold-out show in London and works on view in New York and L.A., Pecis is the it post-lockdown painter.

With a sold-out show in London and works on view in New York and L.A., Pecis is the it post-lockdown painter.

Taylor Dafoe

When I look at the bright, busy paintings of 41-year-old American artist Hilary Pecis, I think: if Matisse had an Instagram account, his feed would probably look a lot like this.

With an influencer’s eye for framing and a fauvist’s love of color, Pecis memorializes the beauty in the banal—a yawning bouquet of flowers in a mason jar, a cup of coffee atop a freshly completed crossword puzzle. Many artists make work about quotidian pleasures, but few revel in them like she does.

It is fitting, then, that after a year in which we were all stuck at home, Pecis’s portraits of domestic life have found a hungry new audience. Her solo show, on view now at Timothy Taylor in London, sold out shortly after the opening. (Prices for the work range from $20,000 to $60,000.)

Her work is also on view in a group exhibition at David Kordansky in L.A. (where she worked as a registrar for half a decade) and in a show curated by Helen Molesworth at Jack Shainman’s The School in Kinderhook, New York.

Meditating on Pecis’s appeal, Molesworth told me recently: “There are mornings when shit is really rough, when the fascists are here and the earth is dying. But even then I can still walk into my living room, see the light hitting something in a certain way and I can think, ‘That is so beautiful.’ There’s something like that in Pecis’s work and it’s very powerful.”

The market is certainly taking notice. On May 25, a 2016 painting of two cats in a garden sold at Christie’s Hong Kong for $225,437 (HK$1.75 million), more than double its presale high estimate of HK$500,000. It marked only the second time Pecis’s work has hit the auction block.

Her profile was on the ascent just before lockdown, too. Last year, Rachel Uffner opened a solo show of the artist’s work in New York. Even though it was only up for two weeks before the world shut down, it sold out, too, for prices ranging from $6,000 and $30,000.

“At that point… the demand for her work was the most I had ever seen for any artist,” Uffner said.

The show marked a considerable price hike from her debut with Uffner back in April 2018—the first time the dealer staged a solo show without meeting the artist in person—when paintings ranged from $3,000 to $6,000. Notably, the late artist Matthew Wong was among Pecis’s buyers at the time; the two went on to become friends.

“She’s a lovely person and others were so excited to see that she was making great work,” Uffner said. “They wanted to see her succeed.”

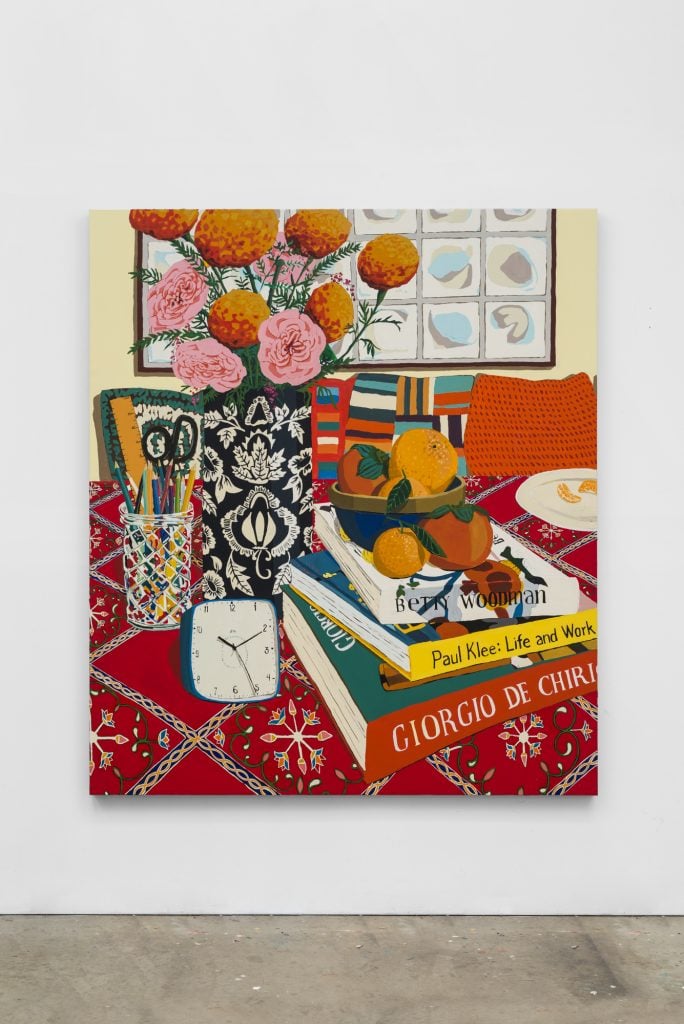

Hilary Pecis, Pink Room (2021). © Hilary Pecis. Courtesy Timothy Taylor, London/New York.

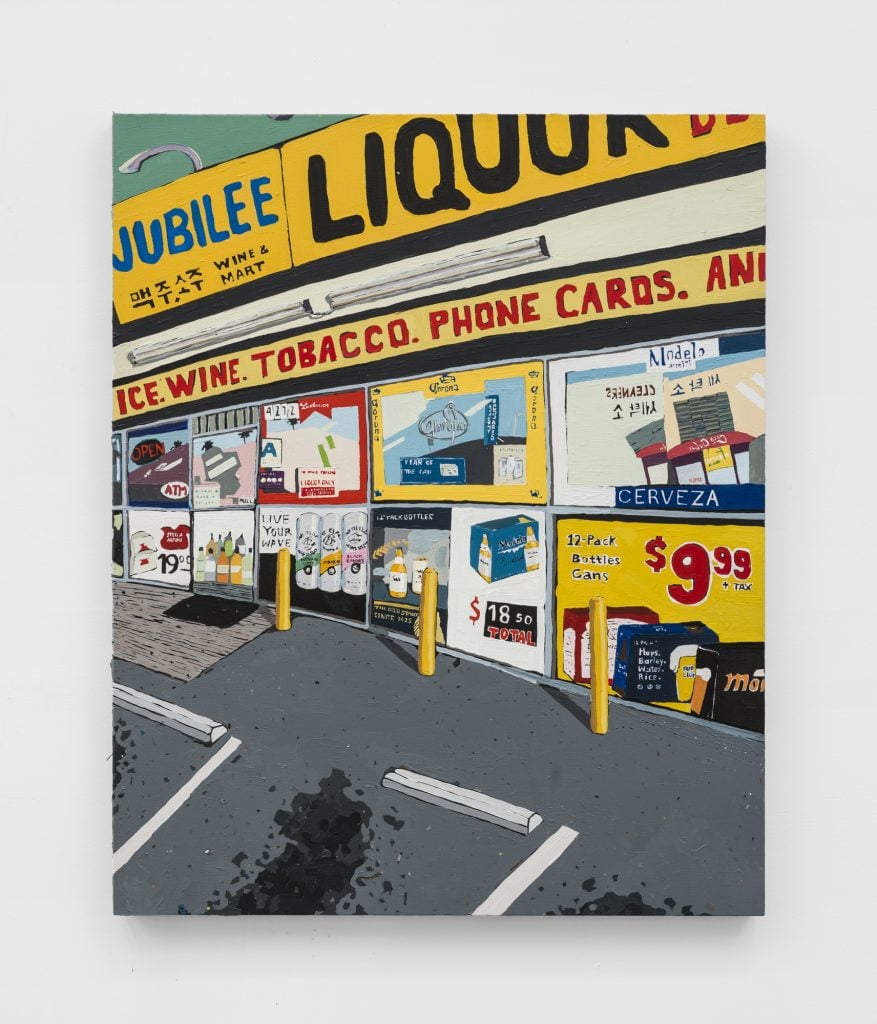

Any piece of writing about Pecis will surely make reference to L.A.—and not just because that’s where she lives. There’s a distinct southern California vibe to her paintings. It’s in the turbid, acid-washed skies of her landscapes and the bungalow-chic designs of her interiors. And it was her move there, in 2014, that transformed her work and ignited her career.

Born in the Bay Area to two civil servants, Pecis went to art school at the California College of the Arts in Berkeley. At the time, she was making fantastical digital collages that resembled Photoshop fever dreams. That work looks nothing like what she makes now. And Pecis is the first to admit that it was not as sophisticated as what she’d go on to do.

“I was trying to defend that work with all these theoretical ideas, but it was all just jargon,” the artist told me over the phone in May. She was calling from her studio, painting while we spoke—a juggle that seemed routine for her. “I like to forget they exist, but my mom has some to remind me that I went through that phase.”

On the advice of an old art teacher, she eventually turned to painting—a hobby she had honed in the background but never fully committed to. It was slow going at first. By 2012, when she had a child, she said, “I really felt like any art career I had to that point was over. And I thought, well that’s okay. If I’m just a Sunday painter for the rest of my life that’s really going to be fine.”

Hilary Pecis, “Breakfast Nook” (2021). © Hilary Pecis. Courtesy Timothy Taylor, London/New York.

But everything changed when she moved to Los Angeles. Escaping the rising rents in San Francisco, she got a gig as a registrar at David Kordansky—her first and only full-time job. Without the hustle of trying actively to build her career as an artist, she finally had time to focus on looking.

“One thing that really stuck out to me is just the way things slowed down,” Pecis said. “I was staying in my house and then making paintings from it. It was really liberating to not feel like I needed to defend anything. When you don’t have all these expectations—it’s very freeing.”

While roughly 50 percent of the artist’s output is still-life painting (the other half is landscape), there’s an abiding stillness to all of her work, regardless of subject matter. If there’s a preeminent L.A. quality to her work, it’s this.

“She’s kind of like our David Hockney,” said Molesworth, before drawing a couple of distinctions. “There’s that free, Laurel-Canyon-pool, everyone-sleeps-with-everyone version of L.A.—the David Hockney version of L.A. Then there’s the domestic L.A., where there’s a bowl of oranges in the corner and you’re looking at a book about Bob Thompson, having your matcha tea—and you are slower than your friends in New York.”

“It’s like the dream of L.A.,” the curator went on. “I think that she embodies that.”

Hilary Pecis, Jubilee (2021). © Hilary Pecis. Courtesy Timothy Taylor, London/New York.

There’s another notable difference between Hockney and Pecis. You won’t find any people in her still lifes and landscapes. “I feel the same way about photographs of myself that I do about painting a person,” the artist explained. “When I see a photo of myself, I just don’t think it sums up who I am. It’s just a flattening out of a person.”

And yet the omission may not be obvious at first. Whether painting her own neighborhood or a friend’s living room, she has a knack for pinpointing the coded aspirational markers of the life we want people to think we live—a poster from a museum, say, or a stack of erudite art books. In other words, you may not get a person’s face, but you get a sense of who they are.

That might be the biggest accomplishment of Pecis’s canvases: their ability to reclaim the charm of these everyday objects in a way that will make you feel seen. “The things we surround ourselves with are signifiers of who we are and who we want to be,” she said.

Now, in their own way, Pecis’s paintings have become an aspirational marker of their own.