For more than four years, the galleries at New York’s Hispanic Society of America have been closed to visitors, its historic Beaux Arts halls in the Audubon Terrace, a turn-of-the-century museum complex designed by Charles P. Huntington in Washington Heights, undergoing a complicated renovation.

“The buildings are limestone, and the roofs are steel girders with glass. The three elements are just not happy together and maintenance has not been good,” Patrick Lenaghan, the museum’s curator of prints, photographs, and sculptures, told Artnet News. “And the roof is only one problem. There’s also the question of lighting and climate control. There are chunks of the building that still have their original 1906 electrical wiring!”

While the project won’t be completed until some time in 2022, the museum is at long last welcoming back the public. This month, it opened a small but impressive exhibition of polychrome sculpture from Spain and Latin America hosted on the building’s lower level, in a space that originally housed the Museum of the American Indian, which moved downtown in 1993.

Since the Hispanic Society shut the doors of its main home for renovation in 2017, it has sent works from its collection to other institutions—staging a traveling exhibition that launched at the Prado in Madrid, and one currently on view at the Grolier Club on the Upper East Side—but this is the first time it has held an exhibition of its holdings on site. (In June, the downstairs gallery was inaugurated with a show of photographs of the Washington Heights neighborhood, in celebration of the release of the locally set movie musical In the Heights.)

Luisa Roldán, Rest on the Flight into Egypt (ca. 1692–1706). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

So how, after all this time, did the curators settle on “Gilded Figures: Wood and Clay Made Flesh” for the soft reopening?

“You had to pick something that would be representative of Spanish and Latin America art and culture, and it had to be high quality,” Lenaghan said. “And there is no other museum outside of Spain that could put on an exhibition like this.”

The Spanish tradition of polychrome sculpture is somewhat unique for Europe during the period covered in the show, from 1500 to 1800.

“In the Middle Ages they painted sculpture and the Greeks painted their statues. Then in the Renaissance, the Neoclassical aesthetic takes over, starting with Michelangelo and even before him, the idea that sculptures aren’t painted takes hold,” Lenaghan said. “They don’t get the memo in Spain.”

Instead, artists working in Spain developed their own style of brilliantly colored, often highly naturalistic sculptures featuring Roman Catholic imagery (the works were often meant to decorate churches). The style was later adapted in the New World, but has received remarkably little attention from major museums—even at the Hispanic Society, which was paying attention to the form decades ahead of the rest of the field.

When the upstairs galleries were open, and filled with massive painting series by Joaquín Sorolla and all the other treasures of Hispanic art, “you would not have noticed these pieces as much,” Lenaghan admitted.

These 17th-century polychrome statues of St. Francis and Mater dolorosa were originally thought to be from Spain. Now, the Hispanic Society believes they were made in Mexico. Photo by Patrick Lenaghan, courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Beyond simply spotlighting polychrome Hispanic sculpture, the show has also allowed the museum to learn more about some of the individual works in the collection.

A life-size 17th-century wooden statue of the Virgin Mary with a gorgeous painted floral robe with gold accents, for instance, had always puzzled Lenaghan, as it never quite fit the style of Spanish works from the period. Now, he believes the sculpture and a similar statue of St. Francis were actually done in Mexico.

“The best is when you reattribute something in your collection and you have an upgrade, and that’s what we did here—Mexican sculpture is very rare,” Lenaghan said.

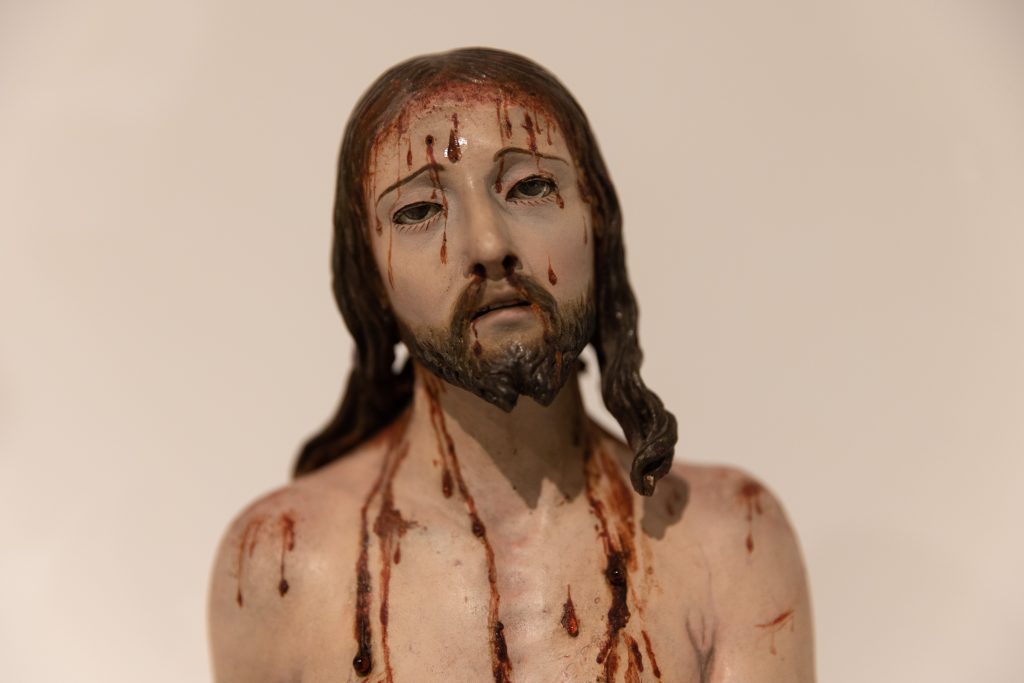

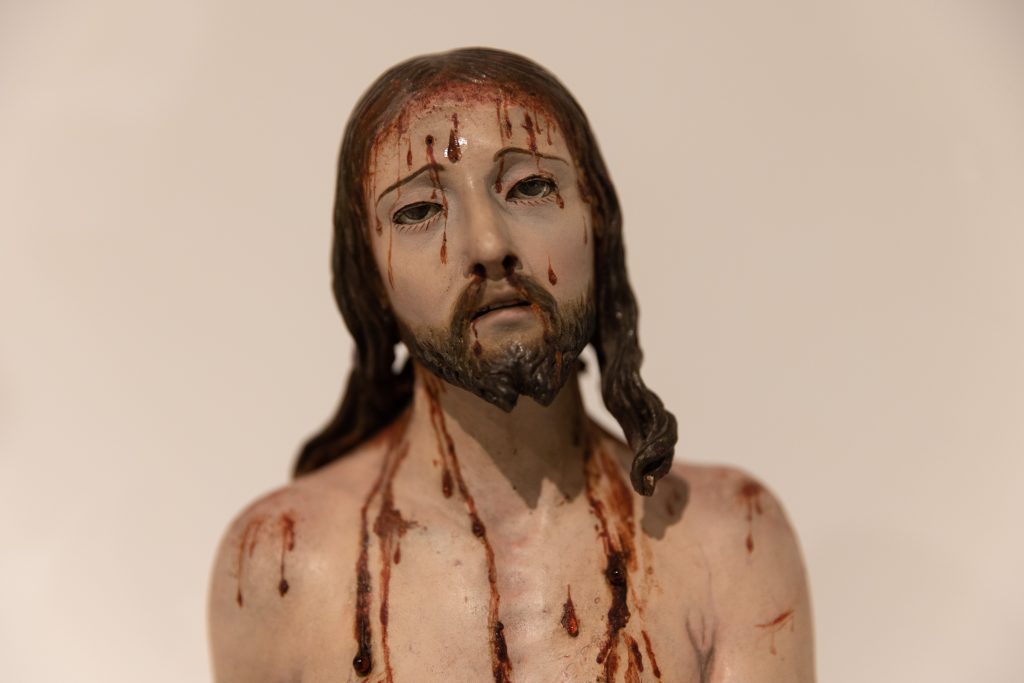

Andrea de Mena, Ecce homo (1675). Photo by Alfonso Lozano, courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Even more rare are the only two confirmed works by Andrea de Mena, the daughter of the artist Pedro de Mena. The busts of Christ during the Passion and a sorrowful Virgin Mary are exquisitely detailed, with tiny glass tears and fine eyelashes. The artist took vows as a nun, but continued working across the street from the convent at her father’s workshop—which means that some of the work attributed to him may have actually been by her hand.

“Andrea de Mena was an extremely talented and sensitive sculptor,” Lenaghan said. “She is probably more prevalent than we realize. She’s a very shadowy figure.”

Her work, purchased as a set by the museum for the equivalent of just $11,454 at a Spanish auction back in 2000, is on view alongside that of another female artist who learned at the hand of her father. Luisa Roldán, daughter of Pedro Roldán, is the better known of the two, having recently received her first English-language monograph, by Catherine Hall-van den Elsen.

Luisa Roldán, Head of St. John the Baptist. Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

There are a selection of Luisa Roldán’s delicate scenes from the bible and the lives of the saints, carved in terracotta and gorgeously painted by her brother-in-law, Tomás de los Arcos. (In something of a reversal, some works attributed to Luisa may actually be by her husband, Luis Antonio de los Arcos.) But there are also a pair of rather gruesome portraits of St. John the Baptist and St. Paul, their heads presented on platters, that have only recently been identified as Luisa’s work, despite being part of the museum’s collection since its opening in 1904.

“Everyone knows her beautiful lyrical tranquil quality and not this absolutely intense gory naturalism,” Lenaghan said. “She is a more sensitive and sophisticated artist than we realized, capable of many different modes. To typecast her based on these pretty nativity scenes is to miss out on the skill and the talent that’s here.”

Most of the works in the show came from churches or monasteries, but other pieces may have come from private homes, as personal devotional objects.

Attributed to Manuel Chili, known as Caspicara Ecuador, The Four Fates of Man: Soul in Hell (ca. 1775). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Among the more mysterious are a quartet of tiny figures attributed to Manuel Chili, an Ecuadorian artist known as Caspicara, titled The Four Fates of Man: Death; Soul in Heaven; Soul in Purgatory; Soul in Hell. A maggot-infested skeleton and a bright red figure in chains, writhing in agony as it tears open his chest, stand in sharp contrast to the man pleading to be released from the comparatively gentle flames of purgatory and the prayerful woman floating in the clouds.

“They’re so unlike anything else. This creation is so unique that’s it very hard to imagine how they would have been used,” Lenaghan said.

The exhibition also shows off recent conservation of many of these pieces—Hélène Fontoira Marzin, the department’s head, is the co-curator—and that work has been made possible in part due to the extended closure. In fact, the staff has been perhaps busier than ever over the last five years, organizing the off-site exhibitions and working to take advantage of time when the collection doesn’t have to be on view.

“I’ve never worked as hard as I have since the museum closed,” Lenaghan admitted.

See more photos from the exhibition below.

Attributed to Manuel Chili, known as Caspicara Ecuador, The Four Fates of Man: Death; Soul in Hell; Soul in Purgatory; Soul in Heaven (ca. 1775). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Andrea de Mena, Mater dolorosa and Ecce homo (1675). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Anonymous Mexican sculptor, Santiago Matamoros (ca. 1600). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Juan de Juni, Saint Mary Magdalene (ca. 1545). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Anonymous Hispano-Flemish Sculptor, St. Martin (ca. 1450–75). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Anonymous sculptor, Imagen de Vestir (ca. 1800). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Pedro de Mena, Saint Acisclus (ca. 1680). Photo courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Luisa Roldán, Head of St. Paul. Photo by Alfonso Lozano, courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

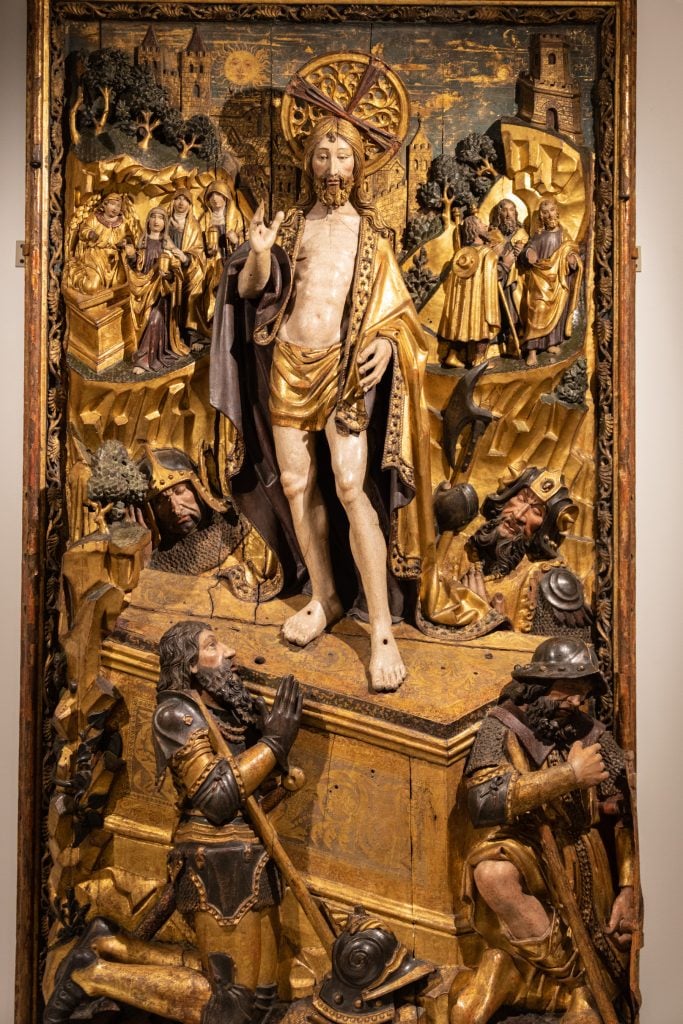

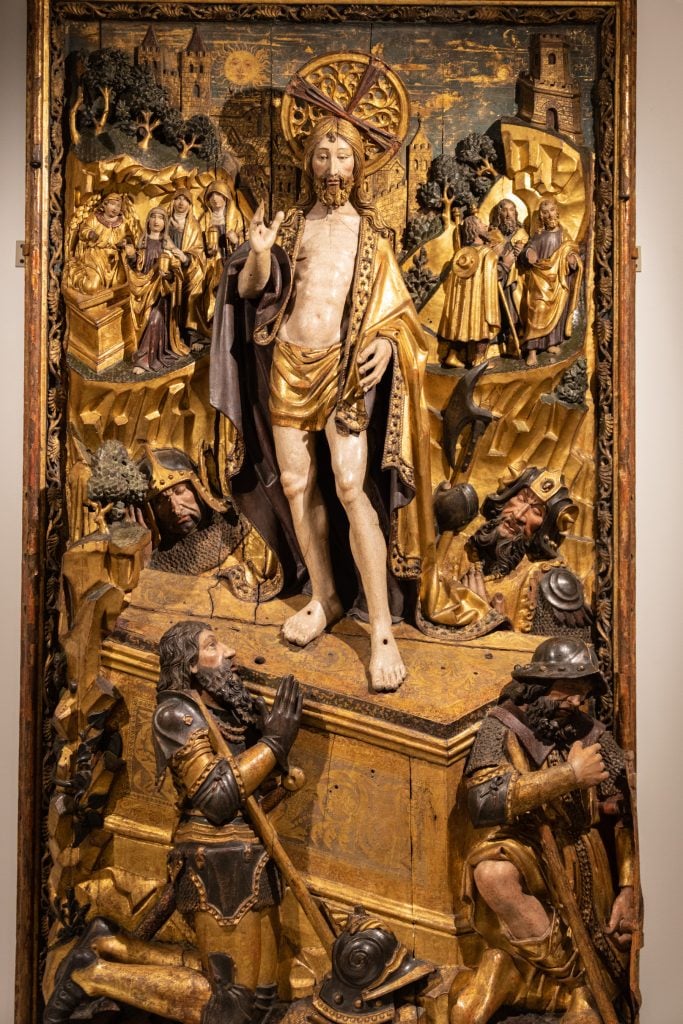

Attributed to Gil de Siloe, The Resurrection (ca. 1480–1500). Photo by Alfonso Lozano, courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

Juan de Mesa, St. Louis of France iin “Gilded Figures: Wood and Clay Made Flesh” at the Hispanic Society of America. Photo by Alfonso Lozano, courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America, collection of Gallery of Nicolás Cortés.

A 17h-century Mexican Mater dolorosa statue in “Gilded Figures: Wood and Clay Made Flesh” at the Hispanic Society of America. Photo by Alfonso Lozano, courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

“Gilded Figures: Wood and Clay Made Flesh” at the Hispanic Society of America. Photo by Alfonso Lozano, courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America.

“Gilded Figures: Wood and Clay Made Flesh” at the Hispanic Society of America, 613 West 155th Street, New York, October 15, 2021 – January 9, 2022.