Reviews

Why Hito Steyerl’s Near-Mystical Denunciation of the NRA at the Park Avenue Armory Lacks Firepower

The installation exposes some hidden histories—but it may also mystify them.

The installation exposes some hidden histories—but it may also mystify them.

Ben Davis

Hito Steyerl’s giant commission at the Park Avenue Armory, a three-screen video work called Drill, has been getting decidedly mixed reviews so far. The German artist is a sharp media theorist in addition to being one of the most celebrated artists anywhere right now—a few years ago, ArtReview voted her the “Most Powerful Person in Art,” stretching the definition of “powerful” to its breaking point, but at least showing the respect she commands. So while I happen to agree that this new work falls flat, at least it’s interesting to try to figure out why.

As a writer of poetic theory (Duty Free Art) and a maker of video art that sometimes reads as a spooky illustration of said theory (Factory of the Sun), Steyerl has forged a particularly fertile formula: She tends to isolate some phenomenon in media, art, or technology, and then spin out its intersections and eerie overlaps with much bigger systems of power, showing sci-fi dystopias bubbling up all around.

In that respect, Drill marks a departure. Made specially for the gargantuan space of the Park Avenue Armory’s Drill Hall as the centerpiece of a small survey of unconnected recent works, this massive video-art triptych does not have a sci-fi flavor or a fanciful, speculative tone. It is, rather, an unusually direct bit of advocacy from Steyerl, all but stating that its premise is a call for tougher gun-control regulations in the United States.

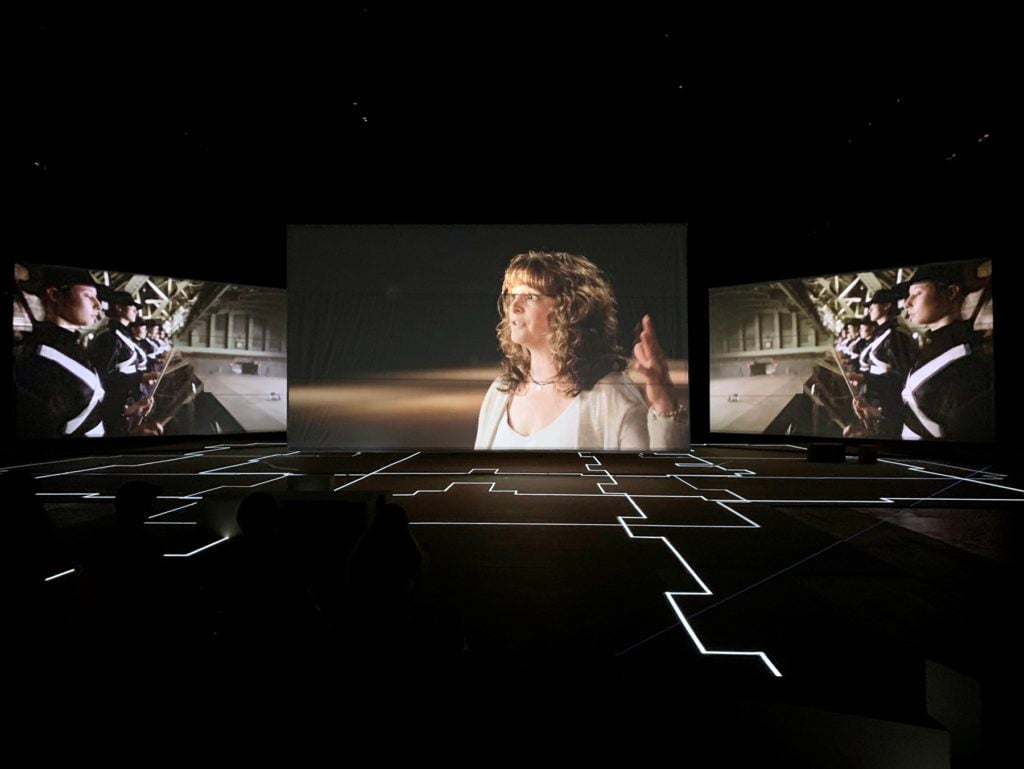

At the height of the Iraq War, critic Pamela Lee coined the term “CNN Realism” for art that imitated the look and emphasis of the news network’s spectacular battlefield coverage, but also risked importing its biases. Drill is something more like “PBS Realism,” a series of talking-head interviews with activists and survivors of gun violence, interwoven with footage of Anna Duensing, a historian and Yale PhD candidate, giving the camera a tour of the Park Avenue Armory’s spectacular building itself, offering thoughts on how this grand space, originally a training site for soldiers, connects to the larger culture of violence in the United States.

At center: Image of Abby Clements, a survivor of the Sandy Hook shooting, in Hito Steyerl, Drill (2019) at the Park Avenue Armory. Image: Ben Davis.

Sometimes this yields unexpectedly effective vignettes, as when Duensing speaks about how the basement of the Drill Hall was once used as a firing range. When it flooded in the ‘80s, the lead from all the bullets embedded in the walls infused the waters, rendering them toxic. The anecdote connects, metaphorically, with the lucid testimony Steyerl has captured from survivors of the 1999 Columbine massacre or recent gun violence in Chicago about how the effects of violence linger on to pollute lives and communities.

But the big epiphany of Drill, its dun-dun-DUN moment, is supposed to be the unveiling of the Park Avenue Armory’s historical connection to the National Rifle Association.

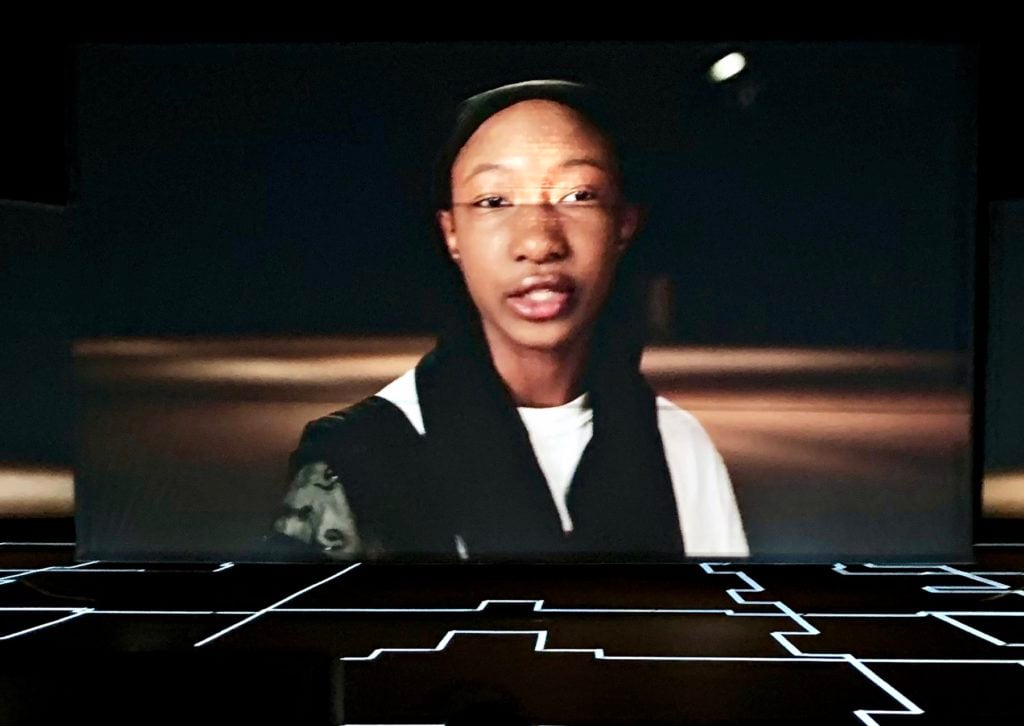

Nurah Abdulhaqq of National Die In, interviewed in Hito Steyerl, Drill (2019) at the Park Avenue Armory. Image: Ben Davis.

The film opens with an epigraph: “History is the act of highlighting whatever is in plain sight.” That mission is what we are meant to think of when Drill shows us our historian/tour guide pointing out an otherwise unremarkable portrait of one Alexander Shaler on the wall of one of the Armory’s chambers. Shaler commanded the 7th Regiment headquartered at the Armory in the Civil War, and would go on to be the first president of the NRA in 1871. At another point, Duensing points to a 1861 Thomas Nast painting titled The Departure of the 7th Regiment to War, explaining how it fired the imagination of another man, George Moore Smith, who chaired the founding meeting of the NRA.

(As you physically explore the Armory’s rooms and halls, darkened for Steyerl’s other films, you will note that the paintings cited in the film are literally “highlighted” by lights.)

Spotlit at left: Portrait of Alexander Shaler at the Park Avenue Armory. Image: Ben Davis.

It’s exactly this big centerpiece revelation that I have the biggest question about. Because what, after all, does Steyerl’s unearthed history actually mean?

The NRA’s diabolical influence on contemporary US life is such that its name is essentially a code word for all that is wrong with politics—at least for this work’s intended audience. Unearthing the gun lobby’s buried presence in this glitzy New York art venue has the effect, therefore, of making the film a kind of ghost story, conjuring a shiver of dread at the dark forces haunting the present.

Duensing mentions, briefly, that when it was founded, the NRA was actually a “social, skills-minded association.” It’s almost an aside—but that’s a key point! A century and a half of history separates the NRA’s founding from now, and that’s plenty of time for institutions to mutate fundamentally. To use an obvious example, think of the difference between Abe Lincoln’s Republican Party, which fought the Civil War, and Donald Trump’s, which makes a cause of clinging to Confederate monuments.

At center: Image of Anna Duensing, public historian, in Hito Steyerl, Drill (2019) at the Park Avenue Armory. Image: Ben Davis.

Even Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, author of a hard-hitting book, Loaded, that places the long history of Second Amendment militia mania in the context of frontier extermination of Native Americans—and which describes the modern-day NRA as essentially a white power organization—stresses the very recent nature of the present-day organization’s activism. Until the ‘70s, the NRA was actually for gun control.

It was in the post-Civil Rights era of backlash and dogwhistles to the “silent majority” that the “right to bear arms” became a kind of shibboleth for reactionary politics. (After all, in the late ’60s the phrase was most associated with the Black Panther Party.) It was then that the NRA morphed into the extremist form that it takes today.

So what history is being unearthed here, besides a name?

Thomas Nast, The Departure of the 7th Regiment to War (1961), spotlit as part of Hito Steyerl, Drill (2019) at the Park Avenue Armory. Image: Ben Davis.

Maybe I’m being pedantic. But I do think that, when you unpack the critical responses to Drill so far, the reason the film ends up feeling slightly off target, consciously or unconsciously, is that it makes a strong claim to being an exposé digging into unspoken political history, but then ends up depending for its impact less on some chillingly trenchant epiphany, and more on a vague shared sense of evil, as if you’d put a flashlight under your face and said the name “NRA.”

This deflection, in turn, can be traced to the fact that Drill‘s site-specific flourishes seem more a genre convention than anything else, an attempt to transcend “PBS”-ness and relate the video to a recognizable genre of institutional critique—that is, to earn its keep as a work of art at the Park Avenue Armory in the first place.

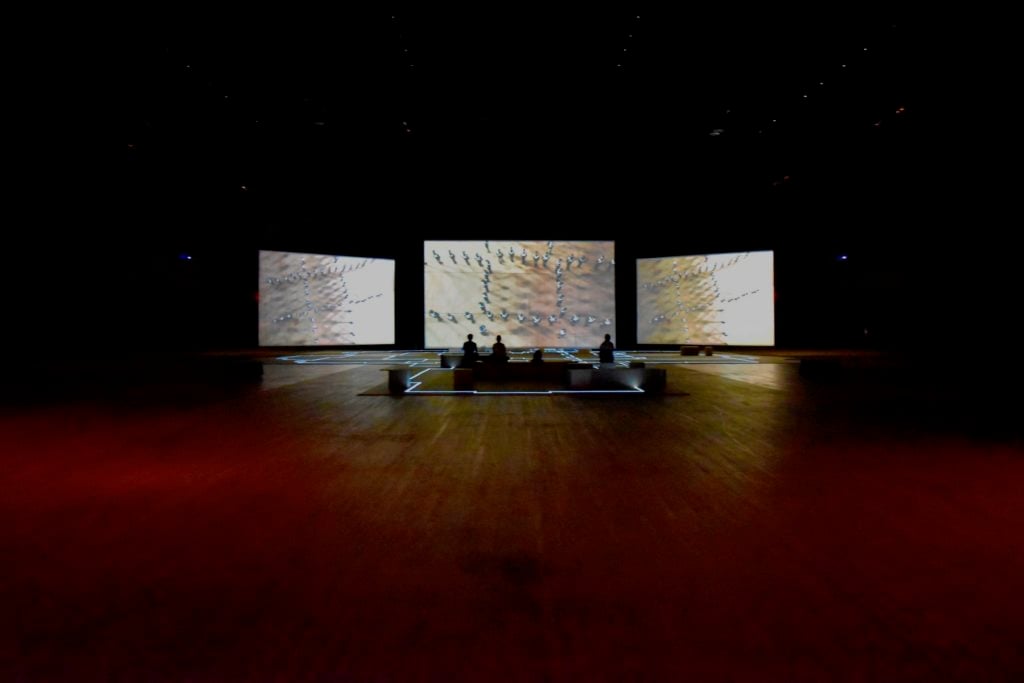

There remains a final, curious aspect of Drill that I haven’t mentioned yet. Sandwiched between the impassioned, righteous testimony of anti-gun activists and Armory trivia, there is footage of the uniformed Yale Precision Marching Band performing in the Drill Hall. The spectacle adds a nicely surreal note, and the churning score gives the film a kind of ominous momentum. It turns out that the music is composed by taking data about gun violence in the United States and processing it into a musical composition.

Installation view of Hito Steyerl’s Drill at the Park Avenue Armory. Image: Ben Davis.

This is a classic Hito Steyerl flourish, offbeat and bracing. But here the gesture cuts both ways.

On one hand, it literally performs the underlying message of the whole piece: That a history of violence lurks beneath martial splendor.

But on the other, Steyerl’s data-driven soundtrack actually symbolizes the exact opposite pull in her art: She has literally taken hard facts about US violence, then rendered them in a form that is aesthetically compelling precisely because it abstracts them into something else.

This seems as good a symbol as any for the potential for a kind of mystification that’s in play here, a tendency for affect to diffuse fact. In that sense, I think you should really see Drill as containing the germs of a self criticism about art culture as well as a criticism of gun culture.

“Hito Steyerl: Drill” is on view at the Park Avenue Armory, 643 Park Avenue, New York, June 20–July 21, 2019.