People

‘I Am Mistaken as the Spokesperson of Native America’: Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds on What the World Doesn’t Get About Native Artists

The artist explains why it's important to share the fruits of success.

The artist explains why it's important to share the fruits of success.

Taylor Dafoe

Since 1981, Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds has lived on tribal land in Oklahoma, far away from the coastal headquarters of the art world. But that hasn’t stopped the art world from trying to bring him in.

Across his four-decade career, the artist, who belongs to the Cheyenne and Arapaho Nation tribes, has been the subject of numerous solo shows, surveys, and public installations, injecting an oft-ignored voice into the culture of the art world. Still, Heap of Birds has stayed true to his roots.

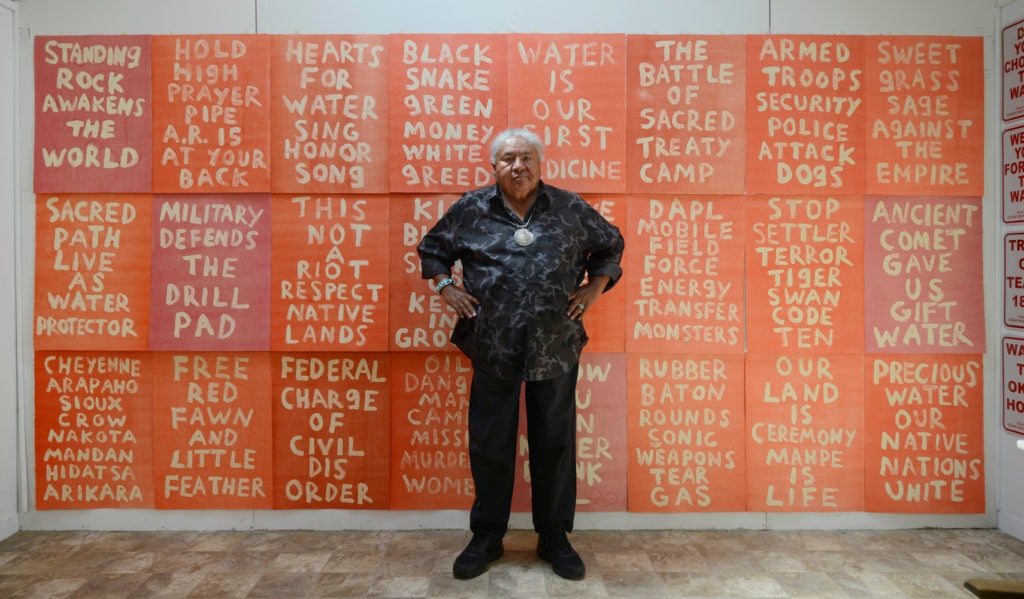

Following a mini-retrospective of sorts at MoMA PS1 last year, the artist has just opened a new exhibition at Fort Gansevoort. Titled “Standing Rock Awakens the World,” it features the debut of a new eponymous installation of blood-red monoprints, each emblazoned with a simple phrase that thrums like a haunting incantation: “OIL / DANGER / MAN / CAMPS / MISSING / MURDERED / WOMEN.”

The title references the protests at the Standing Rock reservation, where demonstrators in early 2016 began speaking out against the Dakota Access Pipeline, a shale-gas line that activists said would leak into and contaminate water sources.

In the show, 24 original prints are each matched by an accompanying “ghost print”—a faded facsimile made with the residual ink of the first. Whereas the first phrases resound like rallying cries, their partners echo like a faint whimper.

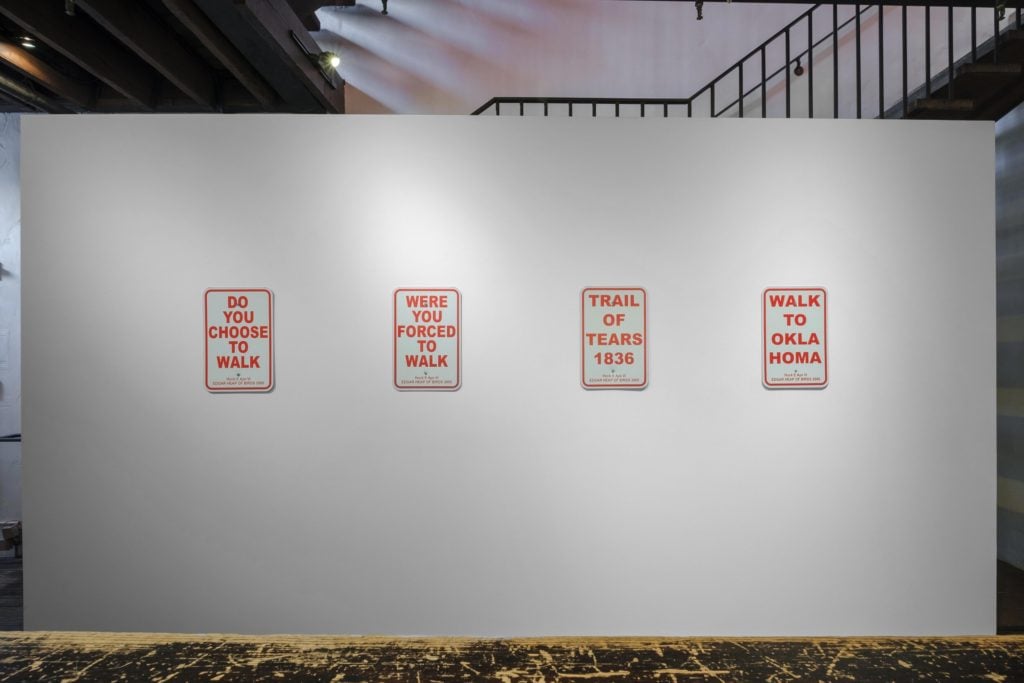

Also included in the show are new versions of his “Native Hosts” series of signs, listing the names of tribes that once occupied New York. Heap of Birds first introduced the series at New York’s City Hall Park in 1988, but the project was censored, and only six of the 12 tribes that lived in the region were represented. The artist has reprised the full work for his Fort Gansevoort show.

On the occasion of the exhibition, Artnet News spoke with Heap of Birds about the censorship episode and his battle with the New York mayor’s office, why success should be shared with others, and why Native peoples live “in the realm of ghost spirits.”

A view of “Standing Rock Awakens the World,” Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds’s exhibition, at Fort Gansevoort. Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

The Standing Rock and Dakota Access Pipeline protests brought a number of issues facing Native peoples to the consciousness of the wider public. What did that movement mean to you?

There’s one print in the new installation that has a list of tribes: Arikara, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Nakota. Those are the original signers of the Fort Laramie treaty [which established territorial claims for Native peoples in 1851]. The activists who came to protest at Standing Rock cited that treaty as their right to come to that land. The tribes had made that agreement and they came to that property on the basis of the treaty, even though America reneged on it.

Today, Native tribes are very separated in a sense. They’re informed and enriched by their separate doctrines and practices, and as a result, they’re not very unified when it’s time to come together to battle something. What meant the most to me at Standing Rock was the unification of tribes. That’s so necessary.

An installation view of the show. Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

Why do you think Standing Rock resonated with non-tribal people?

I think it was the environmental component. It wasn’t strictly a Native issue; it was about water. It was about the pollution of the water. And then, of course, the pipe did leak, just like everyone thought it would.

Can you tell me about the ghost prints? This is a technique you’ve used before, such as in the Surviving Active Shooter Custer installation at MoMA PS1 last year.

It’s a conventional method that printmakers use. When you’re making monoprints, there’s still a residual amount of ink on the plate after the first pull, so you can make a second, fainter print. I use it as a metaphor for the marginalized life of Native people in this republic. We’re so faint. We hardly exist in contemporary society and history is so biased. Couple that with all the massacres where I’m from—there are so many ghosts out there. That’s primarily where the Native people reside, in the realm of ghost spirits. So I vow to always make a ghost.

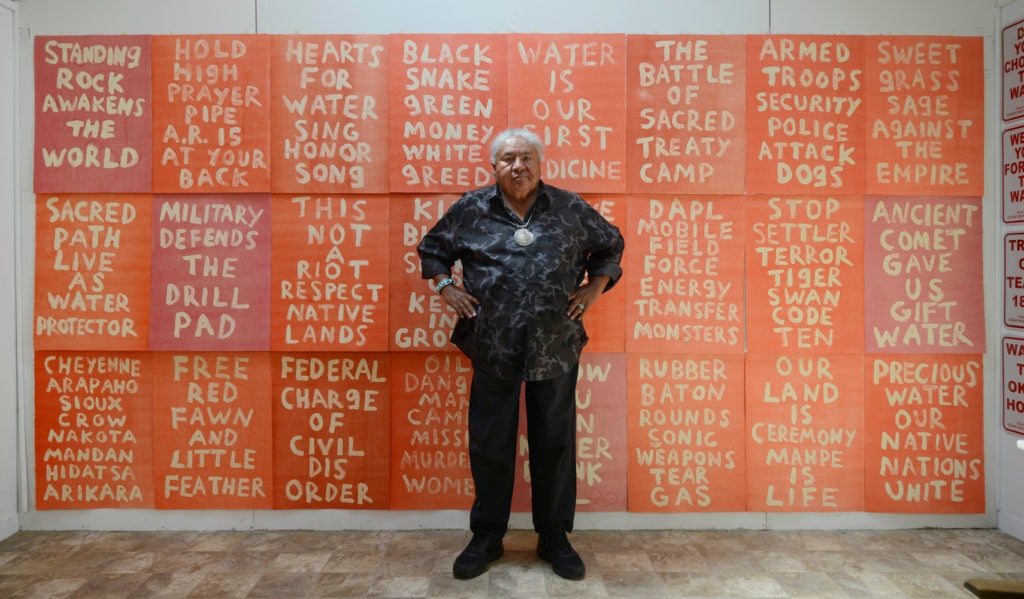

Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Boost West (1990). Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

The show features a new version of your “Native Hosts” series of signs dedicated to the tribes that once lived in New York. It’s the first time you’ve mounted them in the city since you debuted the series at City Hall Park in 1988.

The original was actually censored. Only half of the series was allowed to be installed. Mayor Koch’s office said there could only be six signs, even though there were 12 tribes. We were forced to settle for that. The Public Art Fund didn’t do a very good job supporting it.

Did the mayor’s office give you justification for limiting the number?

I don’t know. It could have been the amount of signage. Maybe it was too many tribal identities around the building. They were scattered all over the park, so it would have been somewhat innocuous, and there were other huge public sculptures installed in the area and they were all allowed to stand. Not the signs. It was too much to have a noticeable presence of Native lives, I guess. The Public Art Fund also said that people were graffitiing on the signs.

I’ve done these installations all over the world. I feel very strongly that whenever you step out the door with art, it’s a dialogue. You have to allow people to respond to your work. If they graffiti it, well, that’s part of their response. But the Public Art Fund said, “Well, if we let them graffiti on your stuff, then we’ll have to let them do it to everybody’s work. We have to clean it.” So I said, “Okay, clean them.” And then when I went to get my final payment, they billed me for the cleaning.

I was a young artist; I didn’t know how to fight back. So I just took the smaller check, even though it wasn’t a very big check to begin with. The whole affair was handled badly.

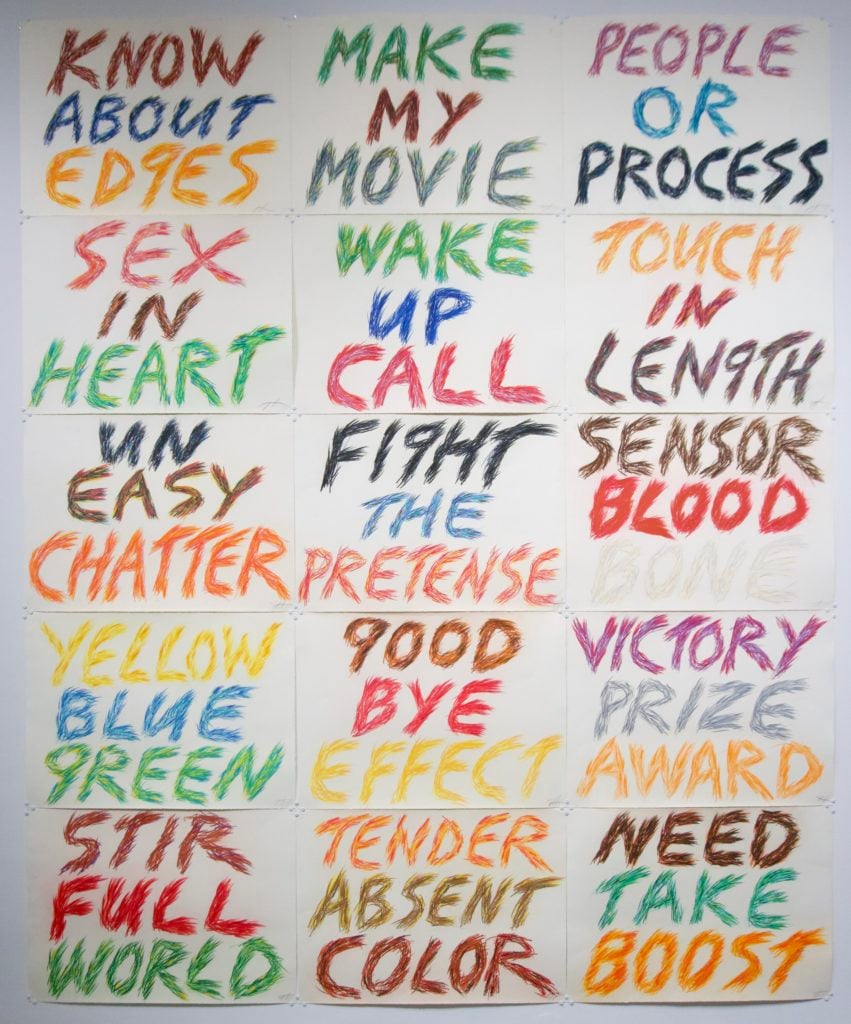

Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Standing Rock Awakens the World (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

The series features the names of tribes that aren’t your own. Is there any tension for you in evoking those other tribes, even though you’re doing it out of a sense of recognition? Have you ever faced any pushback?

The project is about me being a foreigner, really. I’m not from New York, I’m from Oklahoma. I feel strongly that you have to honor your hosts. Everyone that comes here needs to make that acknowledgment. I do, too. I’m a guest in New York for the Native tribes. I do the same thing when I go to Vancouver, when I go to Ohio, when I go to California. There’s no Native America. It’s all individual tribal nations.

I feel like I am mistaken as the spokesperson of Native America when I visit the art world. That’s wrong, but I take that interest and I spin it back into the community. I bring forward Native leaders that are local. I do my work as well, but the first thing I do is to acknowledge the original people of the place. In some rare cases, people from the tribe say, ‘Well, we don’t want to have a sign. We want to make our own sign, or we want to do this, or do that.” If they say that, then I don’t make them. I’ll only do it with their support.

An installation view of the show. Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

Is there a balance to be struck between being a voice for marginalized communities, and being mislabeled or tokenized?

You’ve got to share with the local artists and community members. You can’t be a superstar. That’s what the white man thinks artists are—solo geniuses. And then they want to make me the solo Indian genius. If you’re weak and don’t understand your own life, then there’s a temptation to adopt that premise. That’s a big mistake. They tell you to do that, but that’s wrong. What are you doing to share that with all the young artists? What are you doing to help a community of people? If you claim a tribe, you better know the damn tribe. Otherwise, don’t tell me about it; I don’t want to hear about it. There are enough imposters out there; we need people that are actually investing in a place.

You may make art, but that’s not your whole job. That’s just a tiny little part of your life. It’s not something you believe in or worship. You don’t believe in Chelsea, do you? If you worship Chelsea, you’re in trouble. If Chelsea’s your God, well I’m sorry [laughs].

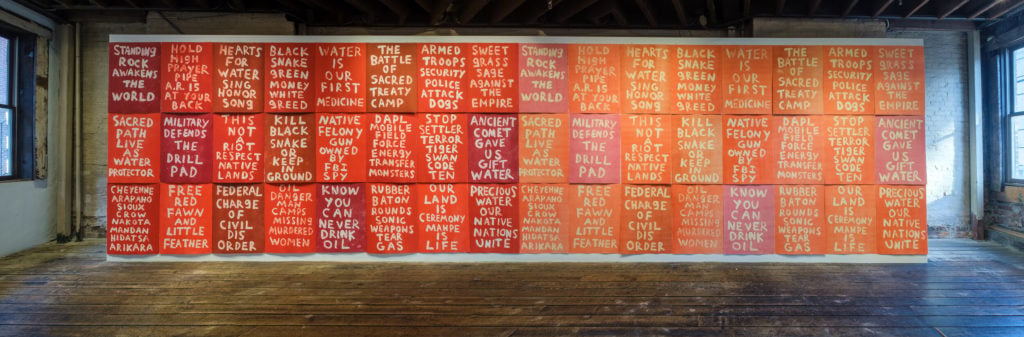

Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Neuf for Autumn I (2014). Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

You’ve made a point of living outside of the art world, both geographically and ideologically. You’ve also enjoyed success, with solo shows at MoMA PS1 and the Honolulu Museum of Art. You’re now an insider in the art world. Does that change your relationship to it?

I’ll back up a tiny bit. There’s a big painting upstairs on the third floor of Fort Gansevoort, from the Neuf series. For me, that painting is about sovereignty. That’s a sovereign painting. I was living in a small canyon when I made the first painting in that series. I had to deal with the cold and the heat, I had to cut firewood and walk to the outhouse in the middle of the night. I was living with a tribe, learning the ceremonies and becoming a contributor, a mentor. All of that informed those paintings. I’ve since painted them in South Africa and Hawaii and Japan and Mexico, but the visual language—the shapes and the atmosphere—that came from here, where I’m sitting right now in Oklahoma.

Success, to me, is spending time with a place and a community of people, giving them credence. You can’t just use them as subject matter. Someone asked me the other day, in an art-world context: “Who are your peers?” I said grandma [laughs]. My brother, he moved into a new apartment and I’m about to go help him move his junk. Those are my peers. I’ve been living in this place for over 30 years. People know me as the guy that helps their son go through ceremonies. They also know me as the art guy who’s written up in the paper or teaching at Yale University. But I’m more useful to them as the man that takes care of their sons.

“Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds: Standing Rock Awakens the World” is on view through February 22, 2020, at Fort Gansevoort.