Archaeology & History

Does This Ancient Rock Art Depict an Extinct Animal?

The painting by indigenous San people suggests they had knowledge about local fossils, says a new study.

There’s a vibrant scene painted on the overhang of a sandstone cliff in the Koesberg mountains, central South Africa, that’s challenging local traditions of paleontology.

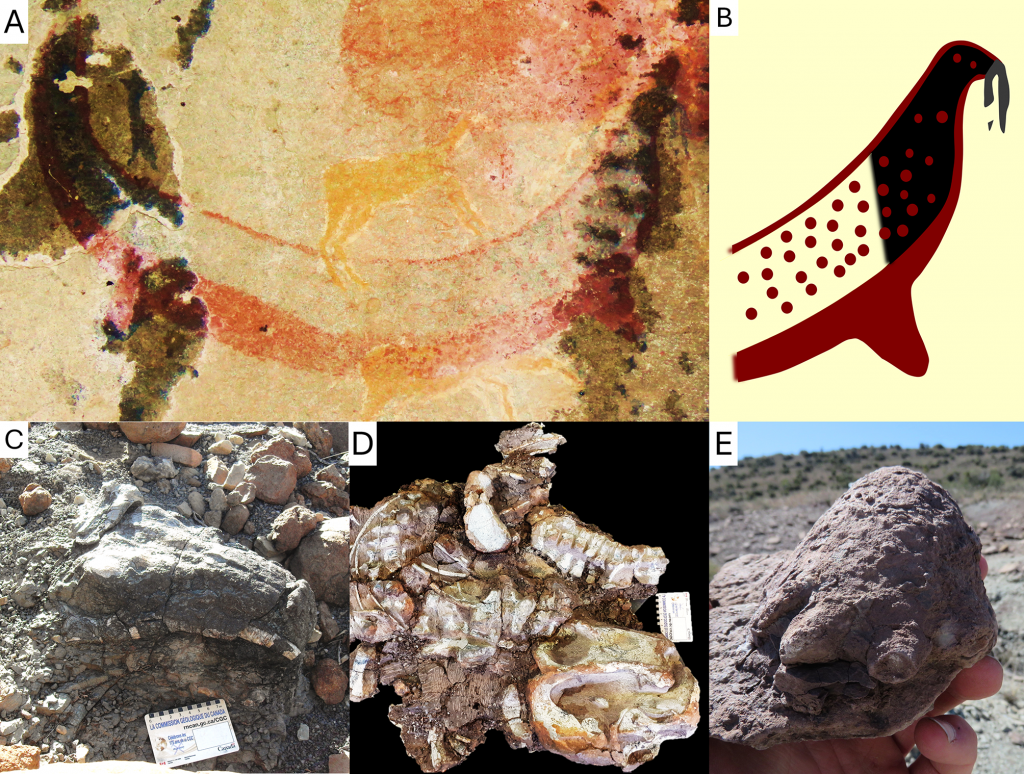

Spanning 30-feet in all, it depicts warriors battling amid flying arrows, hunters on the prowl, and an array of animals including antelopes, an aardvark, and a cat. These details are largely consistent with the countless rock art scenes made by San peoples over the course of hundreds of years.

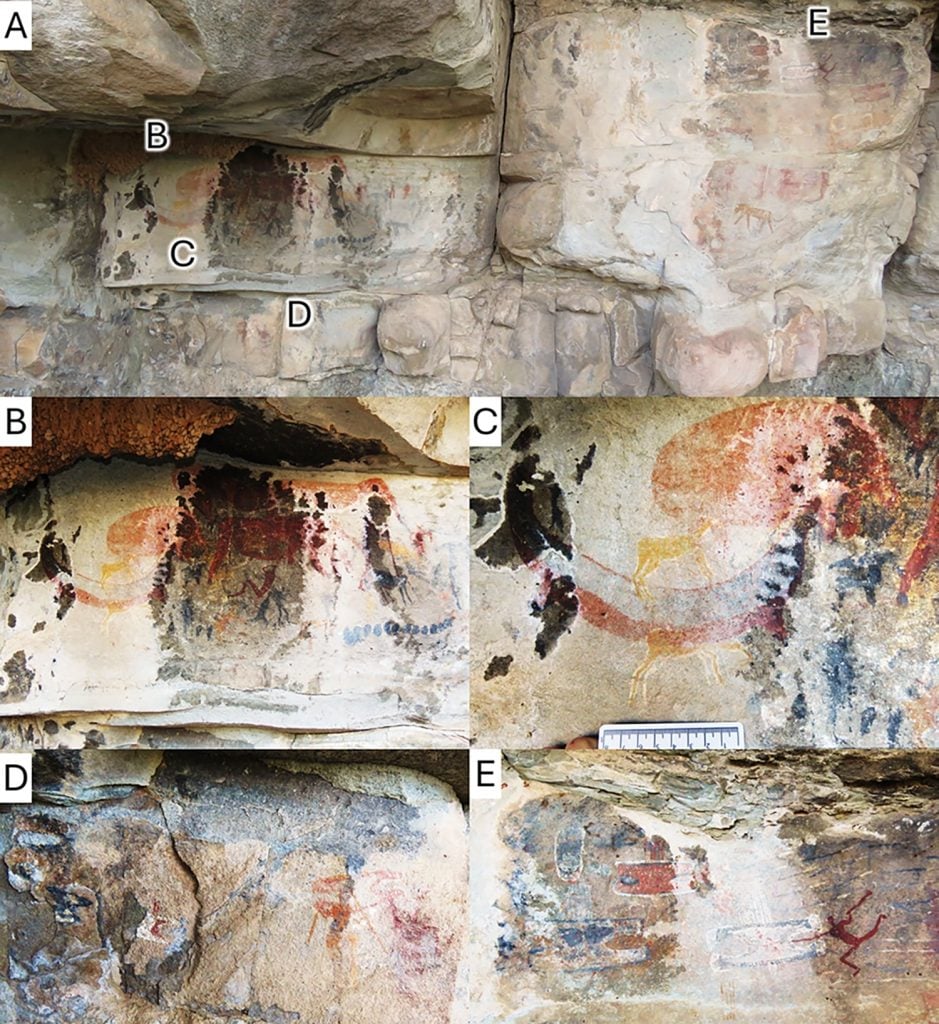

The outlier is a crescent-shaped lizard that has tusks and is marked with red and black polka dots. It’s unlike any beast known to have inhabited the region for millions of years and has granted the rock art its name: Horned Serpent panel.

A paper published in the Public Library of Science (PLOS) on September 18 suggests the mysterious beast is a dicynodont, a mammal-like reptile that went extinct roughly 200 million years ago.

The Horned Serpent panel. Photo courtesy Julien Benoit, doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309908.

It’s believed the Horned Serpent panel was painted by San people between 1821 and 1835 at a South African site known as La Belle France. If correct, it predates the first descriptions of a dicynodont from western scientists by a decade. This timeline has led the paper’s author, Julien Benoit, to suggest a long-running and independent indigenous practice of paleontology by San peoples.

“The ethnographic, archaeological, and paleontological evidence are consistent with the hypothesis that the Horned Serpent panel could possibly depict a dicynodont,” Benoit, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, wrote. “The painting of a dicynodont by the San would also suggest that they integrated fossils into their belief system.”

Benoit first encountered the Horned Serpent panel in a 1930s work by George Stow and Dorothea Bleek that documented rock paintings from across what was then known as South Africa’s Eastern Province and Orange Free State. The way in which the tusks are drawn differ from those of elephants and hippos and sensing that the curious lizard-like rock might be a prehistoric animal, Benoit traveled to La Belle France to assess the painting and its surroundings.

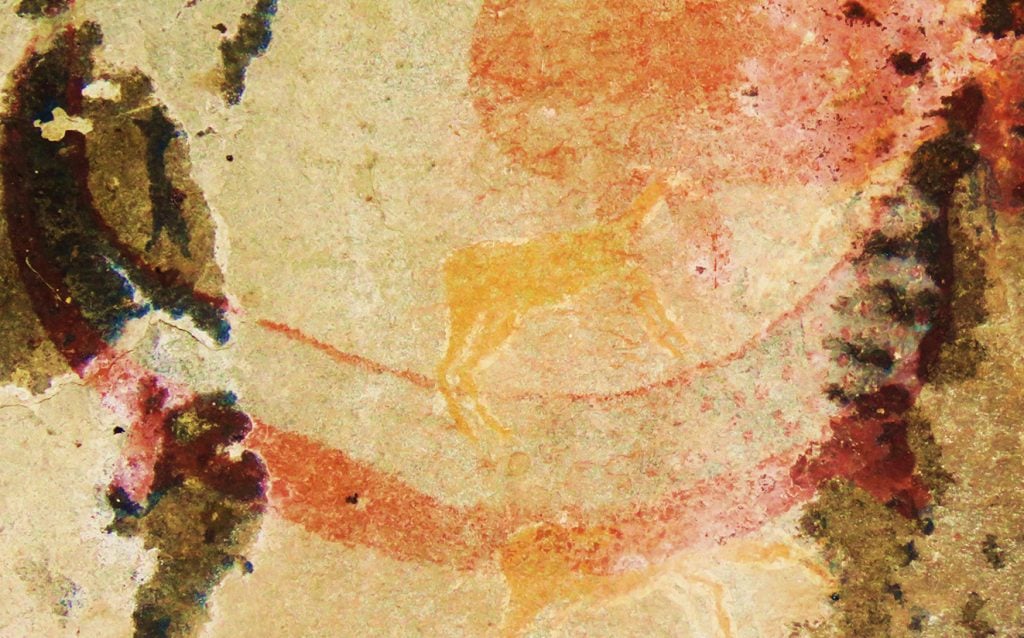

The tusked animal of the Horned Serpent panel. Photo courtesy Julien Benoit

What Benoit encountered was a landscape packed with fossils from the Permian period, including dicynodont specimens, that were widely exposed and easily accessible. Some of the fossils pointed to the creature depicted in the Horned Serpent panel. A mummified foot covered in lump-textured skin was suggestive of the painting’s polka dots and the crescent shape follows the position in which many of the fossilized dicynodont skeletons take.

Given the wealth of fossils in the area, Benoit believes it’s very likely the San people discovered dicynodont fossils, interpreted them as long-extinct species, painted them at La Belle France, and integrated them into their worldview.

“The strangest animals in the San rock art may be interpreted as depictions of Permian reptiles,” Benoit wrote. “Perhaps there may be more dicynodont depictions to be found among some of the paintings and petroglyphs preserved in the Karoo.”