Next year, Ubisoft will celebrate the 15th anniversary of the first installment of its beloved Assassin’s Creed video games with the release of Assassin’s Creed Mirage, the 13th main title in the long-running series. But archaeologists are already concerned about the historical accuracy of its 9th-century Baghdad setting, which aims to recreate the Islamic Golden Age through its open-world gameplay.

The problem, however, isn’t necessarily that the video game company may get things wrong—it’s that experts simply don’t know enough about this overlooked period of history, according to archaeologist Justin Reeve, a news editor at the Gamer.

“Archaeological sites in the region tend to be multiphase, which means that occupation stretched across multiple periods, occasionally thousands of years. This means that in order to keep going down, you have to destroy whatever you find on top,” Reeve wrote. “The trick here is that for most of the last couple of centuries, people have been trying to excavate the bottom levels, blowing through everything above in order to get at the stuff below.”

It is only in recent years that archaeologists have begun taking a closer look at the layers that correspond to the period covered by Mirage, and most of them are publishing their work in Arabic—a language not widely spoken in academic circles and so limits the reach of their findings.

“Whether a lack of sources or just a plain old lack of interest, regions and time periods have received next to no archaeological attention, the Early Islamic Period in the Near and Middle East being chief among them,” Reeve said.

There are also few written records from the period, mainly by only one historian, al-Mas’udi, who was born roughly 100 years after the events he was writing about, according to Reeve. Giving this lack of resources, it remains to be seen how the Ubisoft team will be able to recreate the daily life of the Islamic Golden Age.

Previous entries in the series transport players across time and space to destinations including Victorian-era London, Renaissance Italy, the 18th century’s Golden Age of Piracy in the West Indies, and the U.S. Northeast during the period surrounding the American Revolution.

The Pyramid of Djoser in Assassin’s Creed Origins. Image courtesy of Ubisoft.

The most recent installments have brought viewers to ancient Egypt in 2017’s Assassin’s Creed Origins; Ancient Greece in 2018’s Assassin’s Creed Odyssey; and Norway and the British Isles during the Viking Age in 2020’s Assassin’s Creed Valhalla.

The forthcoming Mirage represents something of a return to the series’ roots as centered on the real-life Order of Hashshāshīn (Arabic for assassins), a sect of Ismaili Shia Islam.

The stories incorporate historical figures such as Julius Caesar and Cleopatra into the action, as well as famous real-world landmarks like the Pyramids of Giza. The game makers work closely with experts—such as Jean-Claude Golvin, a French archaeologist, Egyptologist, and illustrator—to develop a credible (if sometimes-fantastical) plot, as well as an authentic portrayal of the time and place in which the adventure is set.

The careful attention to historical detail in Assassin’s Creed—and nitpicking any perceived shortcomings—has become somewhat legendary.

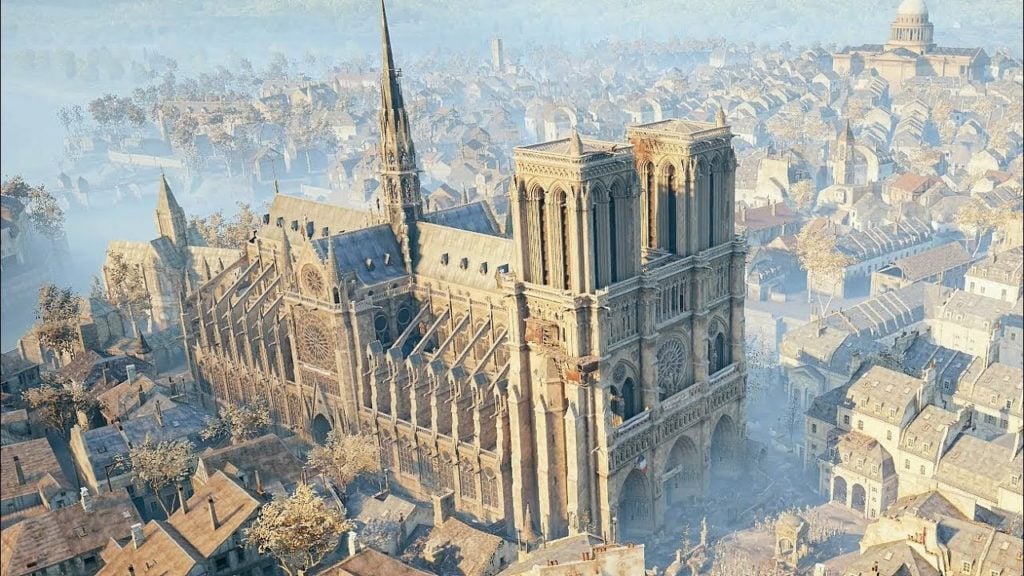

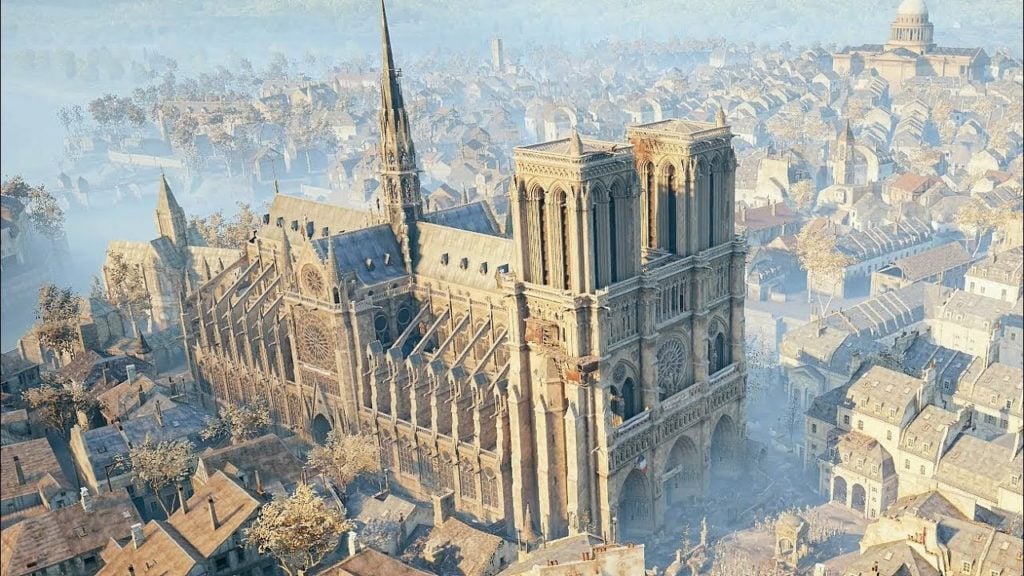

Notre Dame Cathedral, as seen in the video game Assassin’s Creed Unity. Image courtesy Ubisoft.

Video game aficionados were even hopeful that the detailed rendering of Paris’s Notre Dame Cathedral designed by artist Caroline Miousse in 2014 for Assassin’s Creed Unity, which is set in Revolutionary France, might be useful in rebuilding the landmark after a devastating 2019 fire. (It turns out the game doesn’t feature the millimetric precision needed for real-world conservation work.)

But historians and archaeologists have certainly acknowledged the educational potential of the series over the years, with articles on the subject dating back to at least 2009.

Origins even became a university-funded teaching tool thanks to the Twitch streaming channel “Playing in the Past” that ran in 2020 and 2021 during the lockdowns and featured expert walk-throughs of the game using the new “Discovery Tour” mode. It allows you to explore the virtual world without combat gameplay, turning your time-traveling murderer into a less-threatening tourist, as pointed out by a 2019 paper in the journal Advances in Archaeological Practice.

The city of Thebes in Assassin’s Creed Origins. Image courtesy of Ubisoft.

“We were huge fans of the game and utterly inspired by the obvious lengths to which Ubisoft had gone to ensure the world inside the game was as accurate as it could be,” Chris Naunton, who hosted the series with fellow Egyptologists Gemma Renshaw and Kate Sheppard, wrote of the experience. “The virtual Alexandria had clearly been designed according to the textual and archaeological evidence, with all the gaps in the evidence filled in with what seemed like very reasonable conjecture.”

The game is “an excellent tool for studying teaching and popularizing Egyptian archaeology,” archaeology professor Caroline Arbuckle agreed in a presentation at a conference held at the University of British Columbia. “We should be more willing to consider video games as a serious resource rather than just frivolous entertainment.”

Artnet News received a review copy of Valhalla, and was stunned by not only the realism of its gorgeous graphics, but also the chance to “visit” historic sites like Stonehenge (and the less-famous Seahenge) and the famed ship burial at Sutton Hoo, here only partially covered in earth. There were also stunning Roman ruins scattered across the map, and even a small history museum that enlisted players to collect Roman artifacts to earn an “archaeologist” achievement.

Stonehenge in Assassin’s Creed Valhalla. Image courtesy of Ubisoft.

(The blog Archaeogaming, on the other hand, was “met with disappointment” with the game, which reused mosaics and other architectural designs multiple times in different areas of the world.)

Given the series’ track record, video game fans, historians, and archaeologists alike will almost certainly hold Mirage to a high standard. But given the game’s setting, there may be only so much they can do.

“We all need to look past the subject of historical accuracy in games like Assassin’s Creed Mirage in order to ask ourselves why it is that we have such poor knowledge,” Reeve said. “Before developers can ‘do their research,’ the research has to exist in the first place.”

More Trending Stories:

A French Auction House Fired the Employee Responsible for Pricing a $7.5 Million Qianlong Vase at Just $1,900

Archaeologists Have Found the Fabled Temple to Poseidon Recorded in the Greek Historian Strabo’s Ancient Encyclopedia

Has the Figuration Bubble Burst? Abstract Painting Dominates the Booths at Frieze London

For Its 30th Anniversary Gala, Robert Wilson’s Fabled Watermill Center Borrowed a Theme from H.G. Wells and Took a ‘Stand’

Jameson Green Won’t Apologize for His Confrontational Paintings. Collectors Love Him for It

Auctions Live Now:

21st Century Photographs

Buy Now: Robert Lazzarini

40 Under 10