Art World

A New Festival Looks at How Artists Fleeing Nazism Enriched Modern Britain

Mondrian, Schwitters, and Moholy-Nagy are among the artists who fled to the UK during the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II.

Mondrian, Schwitters, and Moholy-Nagy are among the artists who fled to the UK during the rise of Nazi Germany and World War II.

Javier Pes

As the situation worsened in Europe in the late 1930s, many artists found refuge in Britain. Among them was Piet Mondrian. His friend the sculptor Barbara Hepworth recalled his arrival after she and her then husband Ben Nicholson found Mondrian a studio next to theirs in Hampstead, north London. It was a dreary room but within a week Mondrian had turned it into his “Montparnasse studio,” she wrote. He got some cheap furniture, painted it white, and “his wonderful squares of primary colors climbed up the walls.”

The remarkable contribution made by other refugee artists to Britain, as well as the architects, filmmakers, musicians, writers, actors, art dealers, and collectors who brought with them new ideas and a determination to rebuild their lives, will be celebrated in a series of events and exhibitions across the UK next year.

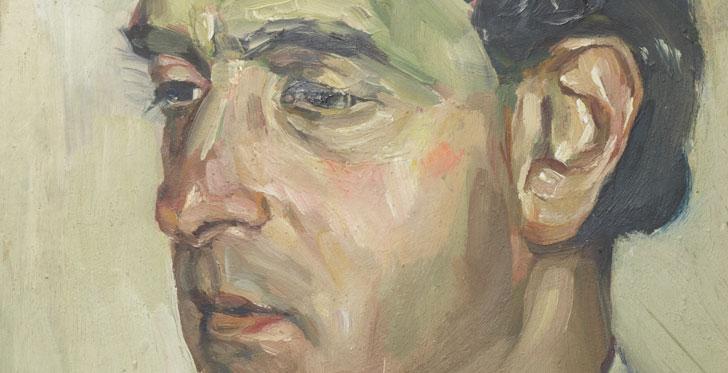

Kurt Schwitters, (detail) Portrait of Fellow Internee Georg Heller (1940). Courtesy of Abbot Hall Art Gallery.

The highlights include famous figures that were forced into exile by Adolf Hitler in the 1930s and ’40s, such as Mondrian from the Netherlands via Paris, Kurt Schwitters and John Heartfield from Germany, and the Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy. The painter Josef Herman had to leave Poland and the potter Lucie Rie escaped from Austria to Britain. But there ware also lesser known figures, in particular women, who made their homes in the UK and will be remembered on the 80th anniversary of the start of World War II.

Among them is the veteran documentary photographer Dorothy Bohm, whose daughter, Monica Bohm-Duchen, is the creative director of the festival, which is called “Insiders/Outsiders.” A historian of the émigrés profound and wider ranging impact and legacy, she tells artnet News that the event is as much about the present as the past. “At a time of increasing xenophobia and with unthinking nationalism on the rise, it is important to remember the contribution that refugees did and can make to British society,” Bohm-Duchen says.

Born into a Jewish-Lithuanian family into what was East Prussia and is now Russia, Dorothy Bohm was sent by her family to escape Nazi anti-Semitism. Now in her 90s, she arrived in England in 1939 as a teenager and went on help launch London’s Photographers’ Gallery in 1971, where she was an associate director for 15 years. She also co-founded Focus Gallery (1998-2004). Last month, an exhibition of Bohm’s photographs opened at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester in the south of England.

Dorothy Bohm, Worthing, Sussex, 1970s. © Dorothy Bohm Archive, courtesy of Pallant House Gallery.

Bohm-Duchen says that among the many institutions she is talking to are the National Portrait Gallery in London about a possible trail through its galleries, while next door she hopes the National Gallery will be involved. She also hopes the Victoria & Albert Museum will focus on émigré photographers. Meanwhile, she can confirm that Sotheby’s London will host an an exhibition about émigré art dealers and collectors.

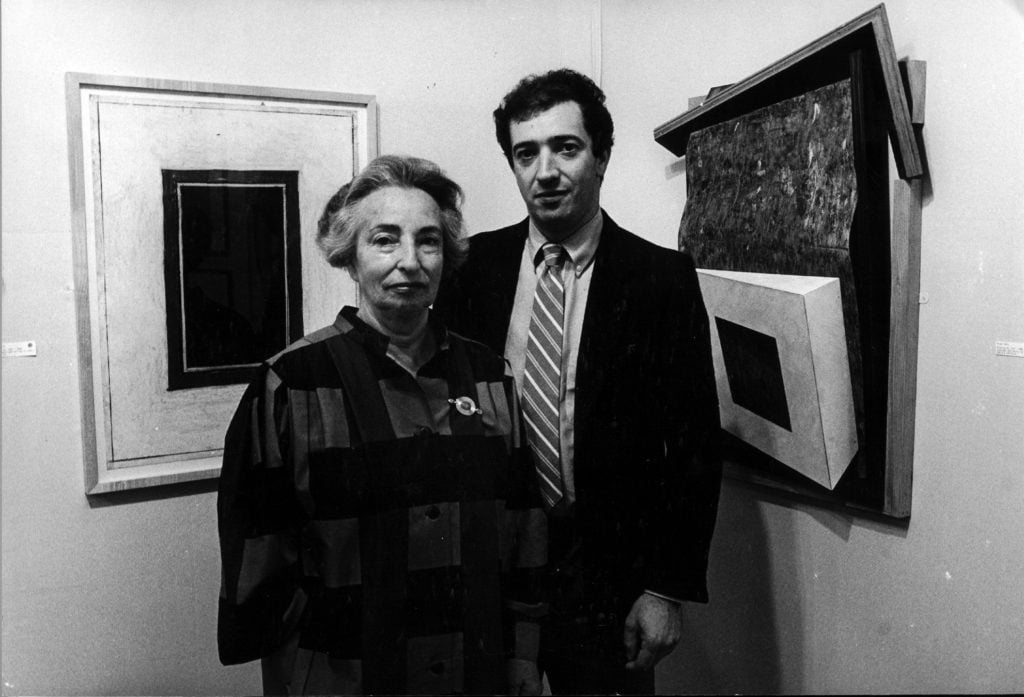

Annely and David Juda, 1985. Courtesy of Annely Juda Fine Art.

The late gallerist Annely Juda was another émigré. Her son, David Juda, the director of Annely Juda Fine Art, says that “many people, particularly those with a German Jewish background, never felt totally accepted as being British. She was basically German. Her father, whose first name was Adolf, fought in the First World War. They were told they were not German but they were all very German.”

Annely Juda’s mother had been a student of the Austrian-born modernist pioneer Oskar Kokoschka. “They were very educated, alive people who were were doing new things,” David says. She was a secretary at a gallery that sold French post-Impressionism and she organized a Jean Tinguely show there, he adds, before opening her first gallery in the 1960s.

Among the predominantly Jewish children rescued on the Kindertransport (children’s transport) from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland were the artists Frank Auerbach and Gustav Metzger. The veteran politician and campaigner for the rights of refugees Lord Alfred Dubs is a patron of the “Insider/Outsider” festival. The curator Norman Rosenthal, whose parents were Jewish refugees, is another patron.

Having “got the ball rolling,” Monica Bohm-Duchen has now embarked on fundraising for the festival. She is also editing a book, which is due to be published by Lund Humphries in early 2019, on the contribution made by refugees from Nazi Europe and their contribution to British visual culture. The project coordinator is Sue Grayson-Ford, who is organizing the show at Sotheby’s. She launched the Campaign for Drawing, which organizes the annual, nationwide “Big Draw” event.

Bohm-Duchen says that it’s important to remember those who were interned, including Schwitters and Heartfield, along with thousands of German-speaking refugees. Regardless of their opposition to Nazism, they were classed as “enemy aliens,” when a German invasion looked imminent in the spring of 1940. Winston Churchill is said to have declared: “Collar the lot.”

Upon his release, Schwitters and fellow refugee artist Hilde Goldschmidt lived in the Lake District in the north of England, where he created his celebrated Merz Barn. They are the subject of a display at the Abbot Hall Art Gallery in Kendal.

After Paris fell to the Germans, Mondrian left London for New York. “I shall always remember his eyes and elegant figure in the street,” Barbara Hepworth wrote, recalling the moment she and her young family left London for St. Ives in Cornwall. “What he created was the beginning of something—and opening of the door to us all.”

“Sussex Days: Photographs by Dorothy Bohm,” through September 30, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester.

“Hilde Goldschmidt and Kurt Schwitters,” display (not dates), Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal.