Out of the blue, in late 2020, I received a cold call from Hans Schroeder-Rozelle, who had seen my byline on articles about art from Germany and Austria. He asked whether I knew of the Austrian artist Otto Muehl, and that two exhibitions on Muehl’s work were running in Vienna.

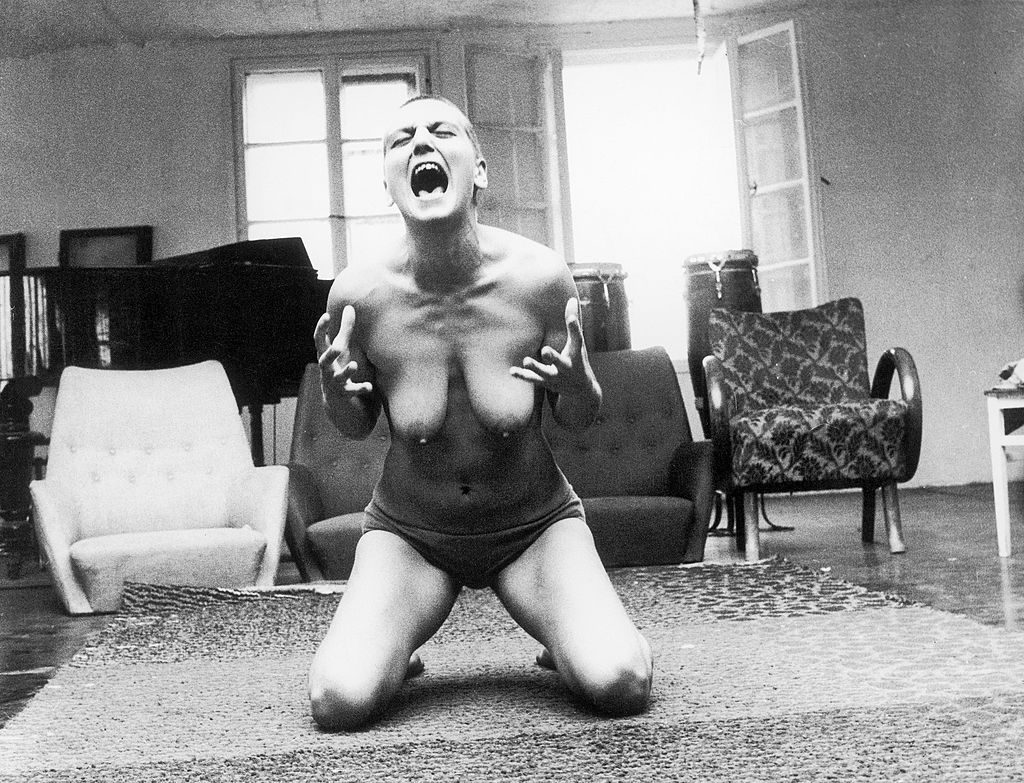

I certainly knew of Muehl, a scandal-ridden protagonist in the Viennese Actionism movement of the 1960s and ’70s, which consisted of a loose group of performance artists including Günther Brus and Hermann Nitsch. The Actionists were known for taking the broader avant-garde artistic movements of the time—like Fluxus, the Happenings of Allan Kaprow, even the work of Carolee Schneemann—and blending art and life to new extremes. Their performances involved feces, blood, and other bodily fluids in often violent acts where the human body became a site for abjection and provocation. Most art historians interpret Viennese Actionism as a reaction to postwar Austria’s conservatism and post-Nazi trauma. Actionism has always been controversial.

Yet Muehl’s legacy was wrought by a controversy that was exceptional even among his peers—about which I would soon learn more from my caller. In the early 1970s, and well known in Austria’s art avant-garde scene and beyond, Muehl founded a commune called the AAO. What began as an anti-capitalist project, liberated from societal and even artistic stricture, over time became increasingly authoritarian—the authority being Muehl. By the early 1990s, some communards tipped authorities off that Muehl was sexually abusing young girls who were living there. Details range from the uncomfortable to the truly harrowing. His denigrating and often dictatorial tone in some footage is as shocking as the alleged sexual acts, some of which were taken to court. The commune dissolved in January 1991, and the artist spent seven years in prison for sexual abuse of minors and drug-related charges.

A toxic person making notable art is not a new concept, but after delving deeper into Muehl’s dark world, I faced difficult questions. Since his death, the #metoo movement has brought renewed focus to abusers, rattling legacies of famous artists. At the same time, we are witness to culture wars, including recent calls for partial or total censorship of art. What lines divide art, an artist, and his crimes?

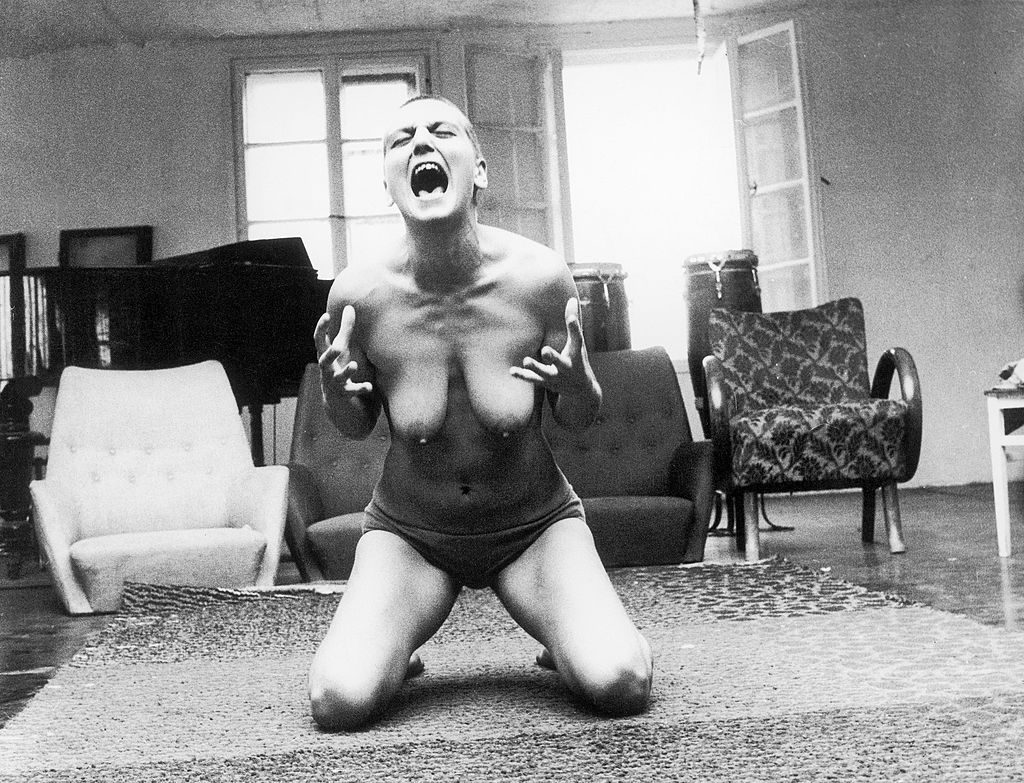

Liberation-scream of a member of the commune of Otto Muehl, Vienna. (1975) Photo: Imagno/Getty Images.

A Dark Star

Back to my caller: Schroeder-Rozelle was himself a communard from the mid-1970s until the group dissolved. He co-founded an initiative called Re-port in 2003 together with a group of former communards. Its apparent aim is to assure that Muehl’s crimes remain known to the art world—including critics like me. So, if the art world attempts to canonize and perhaps capitalize on Muehl, who died in 2013, ex-communards like Schroeder-Rozelle would like to ensure clarity and fairness.

Researching Muehl’s life means falling deep into a rabbit hole of German-language press reports. German and Austrian writers have been both forgiving and vehemently damning of his failed utopian experiment (there’s little in English on Muehl besides an intriguing piece written by Jamieson Weber and Alison Gingeras in a 2018 issue of Spike magazine). There have been heady discussions around exhibitions of his work at Viennese institutions like the Museum of Applied Art (MAK), in 2004, and the Leopold Museum, in 2010.

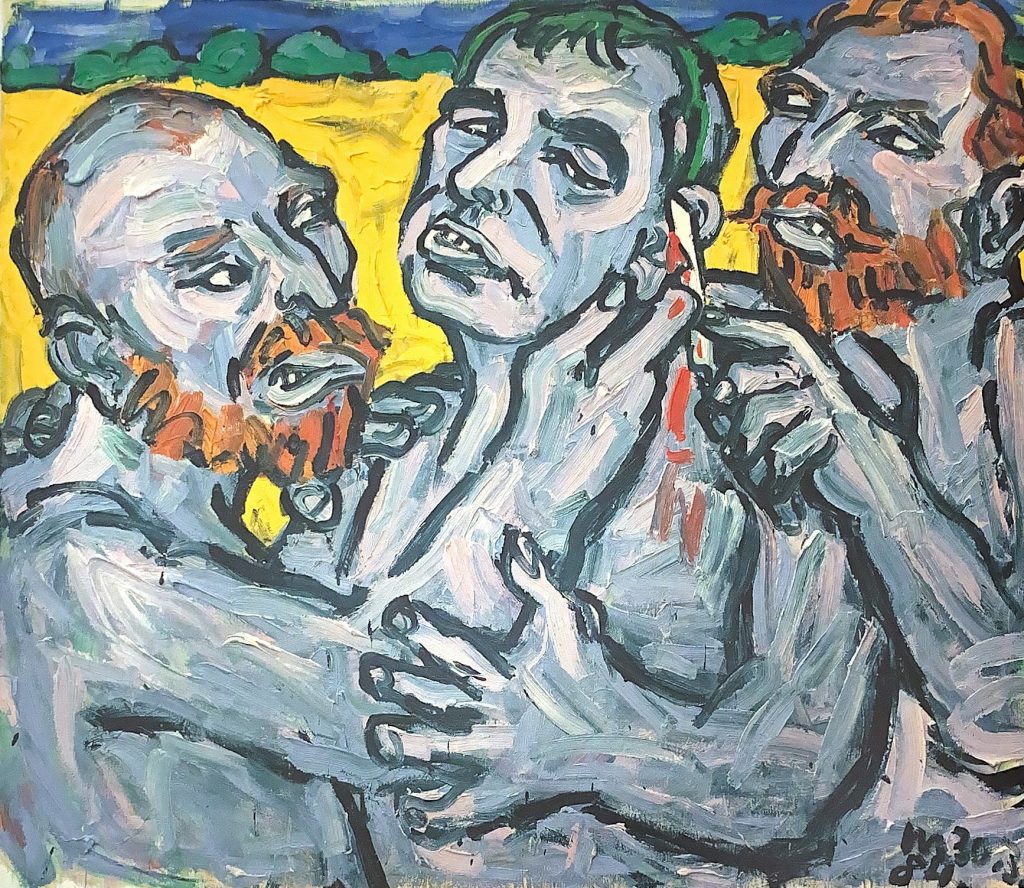

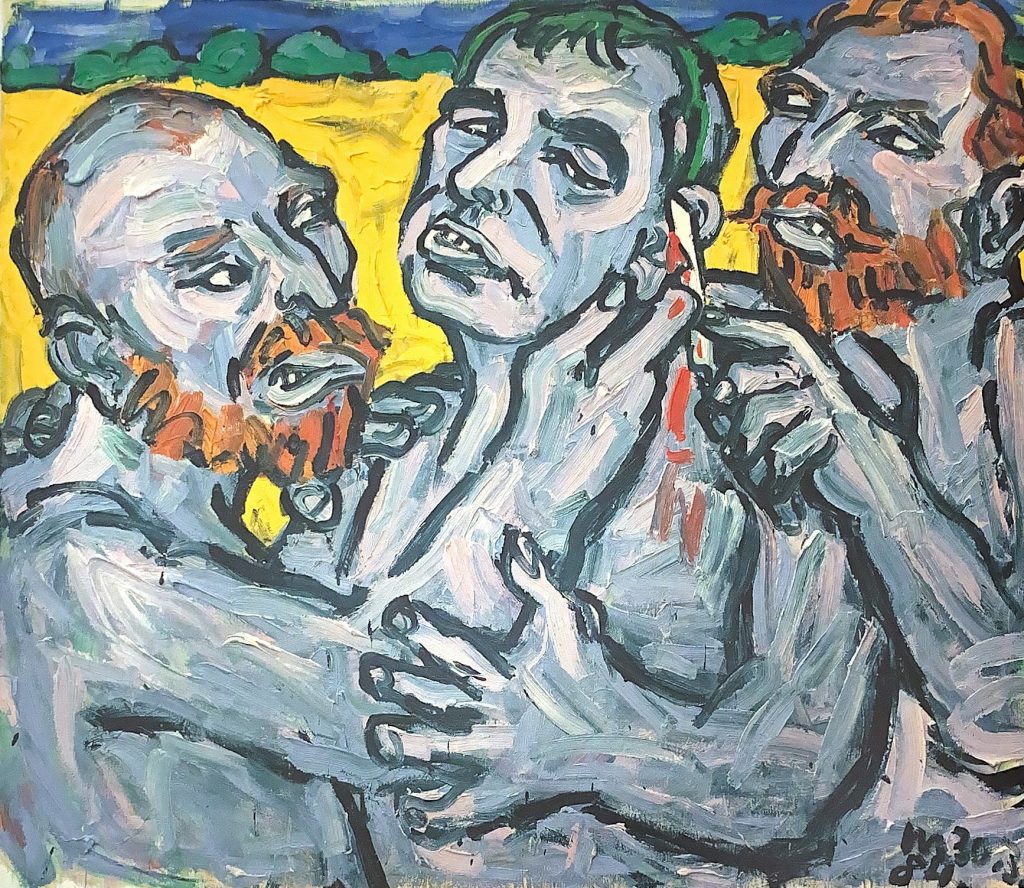

Otto Muehl The Initiation (1984). Image courtesy: W&K – Wienerroither & Kohlbacher.

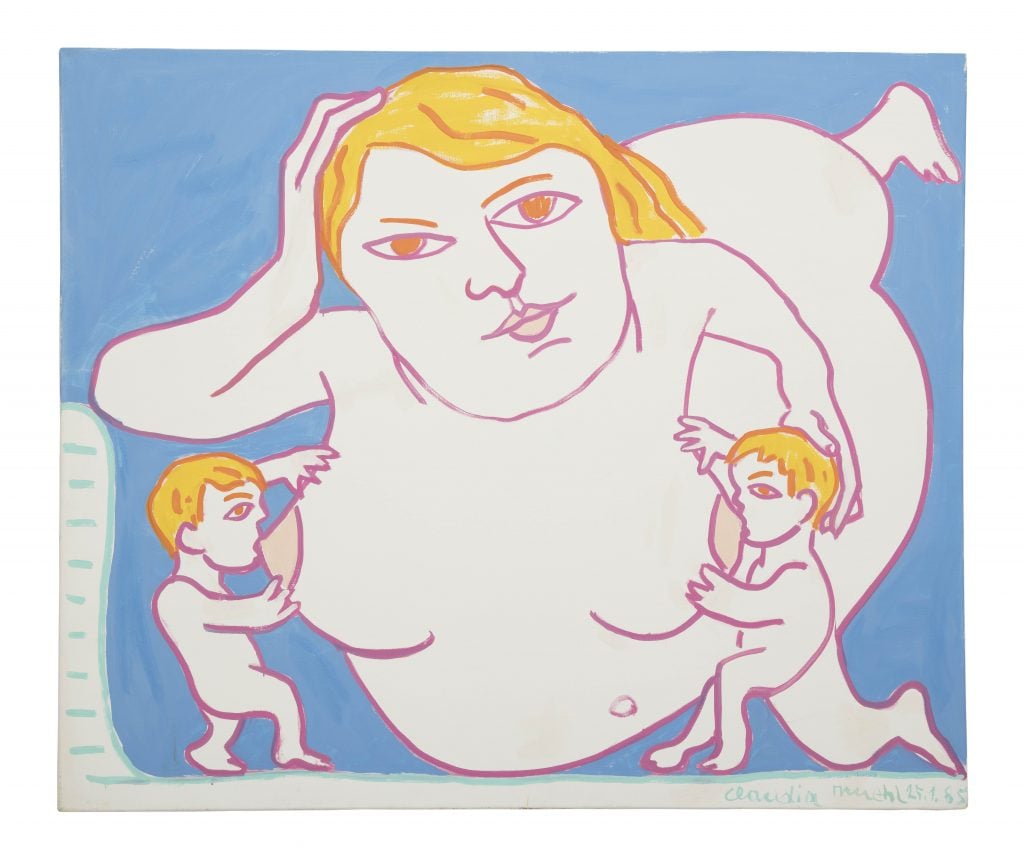

Researching his post-Actionism oeuvre means discovering cycles of work—aquarelles, paintings, texts, sculptures, videos, and of course performance—that intentionally depict base impulses manifesting in images of rape, castration, and ejaculation, but also Poppy, cartoonish depictions of nude pregnant women, nursing babies, and Hitler. There are drawings of the psychological development of an ideal human. There are roughly rendered “bad painting” self-portraits, as well as Expressionist abstractions and lots of fascinating sketchbooks in which Muehl, for example, parses the work of Joseph Beuys. There are works on canvas made from the ashes of the communards’ diaries, burned as evidence because Muehl knew the authorities were on to him.

In many of the works there’s a palpable sense of power: footage of commune life shows Muehl gleefully grunting as he slams glops of paint on large canvases as communards whoop and yell, cheering him on. It’s like Jackson Pollock in primal-scream therapy. Muehl saw no boundary separating art and life.

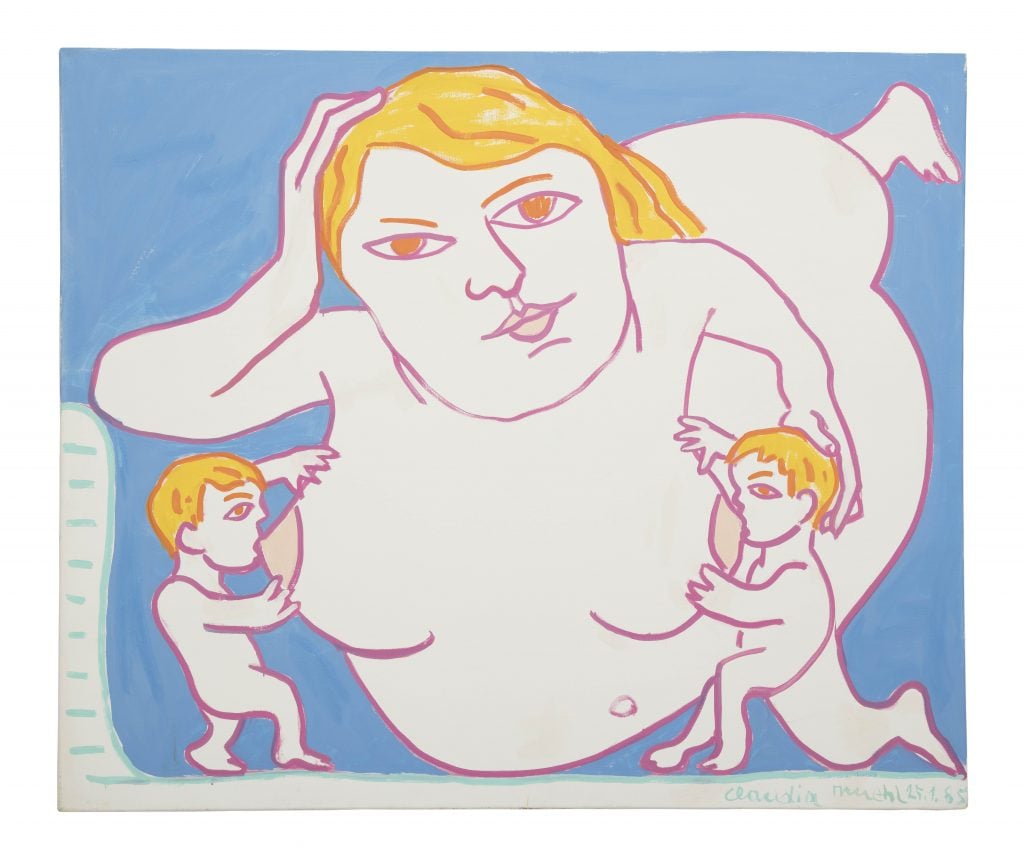

Otto Muehl, Claudia, (1985). W&K-Wienerroither & Kohlbacher, Vienna.

Born in 1925 in a small town in Austria, Muehl fought on the front for the German Wehrmacht, the Nazi armed forces. After the failure of his marriage in 1970, Muehl, disdainful of the bourgeoisie and its trappings, wanted to create a new kind of community (Actionism’s heyday was winding down by the end of the 1960s).

The commune began in Vienna in his apartment before moving to Friedrichshof, south of the city. The communards led experimental lives on the estate, to say the least. AAO (short for Aktionsanalyse Organisation or Action Analysis Organization”) referred to an informal psychological methodology in which neuroses could be overcome through group performative therapy. AAO actively recruited throughout Europe’s alternative scenes, preaching its anti-capitalist, common-property, free-love philosophies. Hundreds of inspired young people joined. When they did, their heads were shaved, many wore overalls, some even wore baby pacifiers. Art was always part of the program.

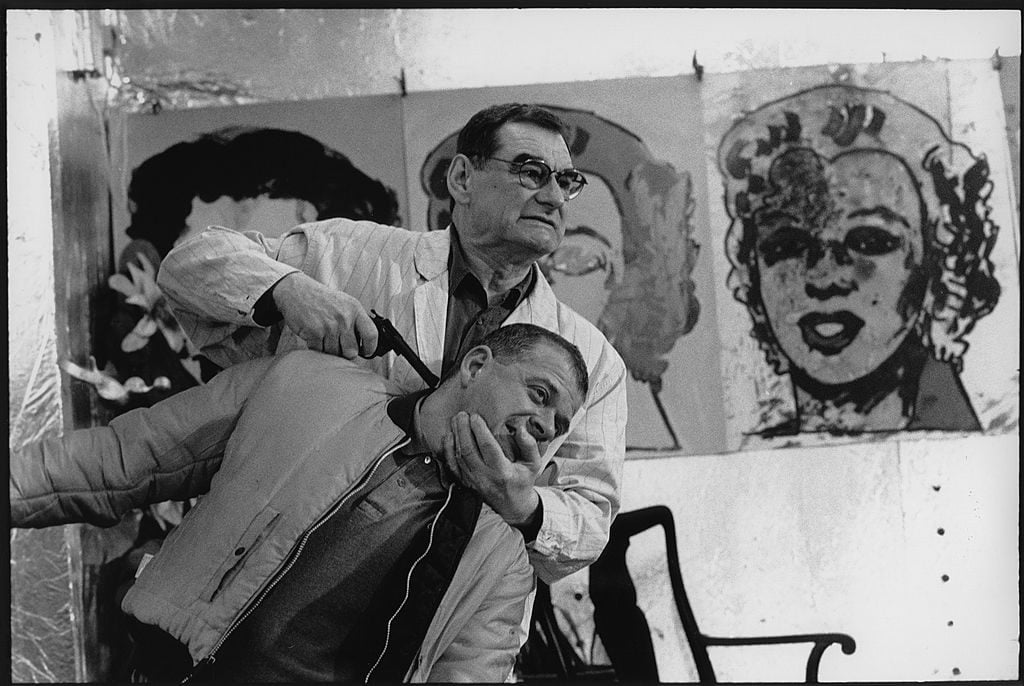

A Happening by Otto Muehl and Guenter Brus at Porrhaus in Vienna in 1967. Photo: Imagno/Getty Images.

But the commune became increasingly authoritarian at Muehl’s behest. According to reports from former communards, articles, and documentaries, monogamous relationships were forbidden and men were not given rooms but had to find different women to sleep with each night. The AAO rituals included symbolically “murdering” one’s parents and homosexuality was considered depraved. Muehl also ranked all communards based on his preferences, and his favorites could order underlings around. At its largest, about 600 communards lived in Friedrichshof; a generation of children was born. Outposts operated in various European cities and on one of the Canary Islands, on a prime piece of seaside real estate.

According to reports from former communards, sexual initiation for girls began at age 14 with Muehl, who by this time was an old man. Fourteen-year-old boys initiated with Claudia, his wife or “first woman.” In prison, Muehl painted hundreds of works before founding another, much smaller commune in Portugal, mostly made up of loyal remaining members, after his release. It operated until his death, at age 87. On YouTube, there are a few interviews with Muehl from his post-prison years. He disturbingly shows little remorse; in one he brags about his sexual prowess and how much he enjoyed being toweled off by teenagers after his showers.

Installation view of “Change: Paintings from the 1980s” on view at W&K – Wienerroither & Kohlbacher. Image courtesy: W&K – Wienerroither & Kohlbacher.

The Reckoning

The reverberations around Muehl and his work are entering a new stage of reckoning. There are divergent views on how to handle Muehl’s posthumous legacy, and little agreement between the parties. The problem of Muehl might also include financial ethics: Dead artists with intriguing stories tend to sell well over time. The artist’s auction record was set at $123,000 for a painting sold in 2014, the year after his death, and prices for his works went on to spike by 38 percent. But then, at the height of the #metoo movement, works by Muehl flooded the secondary market. In 2018, $789,613 worth of works by Muehl sold at auction; the following year, another $781,585 sold, according to the Artnet Price Database—a 162 percent increase from the total in 2017.

Despite the twists and turns of his legacy, the value of Muehl’s art has stayed relatively stable, averaging around $15,000 at auction, and with sales regularly reaching above $50,000.

The plot has recently thickened. In 2019, the two bodies handling Muehl’s thousands of remaining works, the Sammlung Friedrichshof (the commune’s collection, which houses about one-third of Muehl’s work and which still operates as a cooperative) and the Archive Otto Muehl (which has the other two-thirds in Portugal) were united into Estate Otto Muehl.

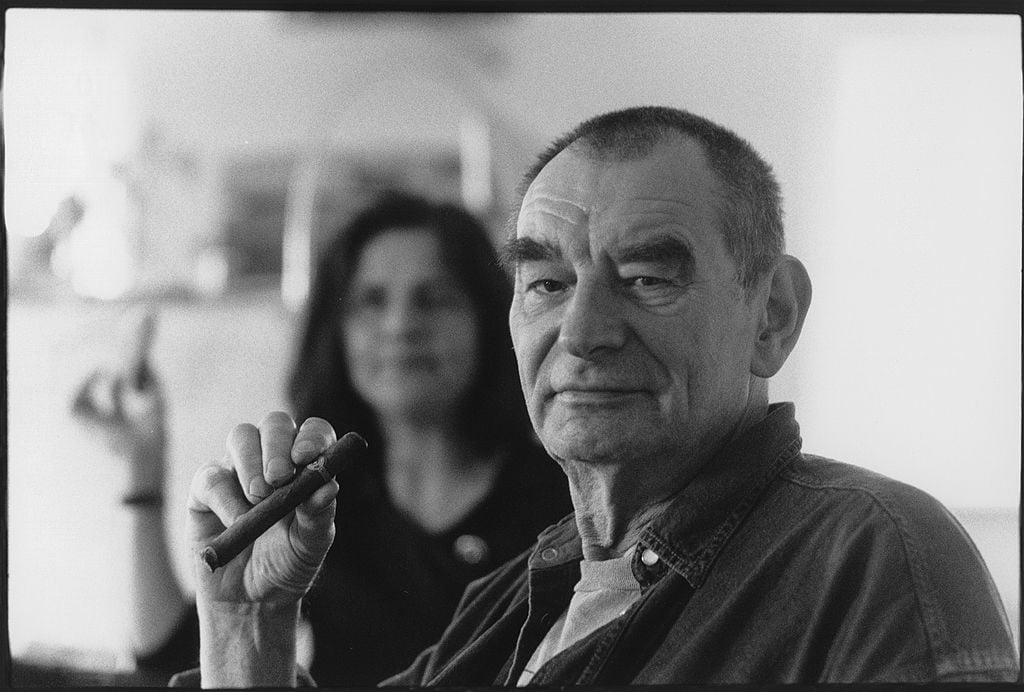

Hubert Klocker, director and chief curator of the Sammlung Friederichshof and the Estate of Otto Muehl. Photo: Philipp Schulz.

The estate is administered by Hubert Klocker, an art historian who has been engaging with Viennese Actionism for decades, curating shows on the topic including one at Hauser and Wirth, and facilitating acquisitions by the Getty Research Institute. In late 2019, the estate reopened as an exhibition space on Schleifmühlgasse, on one of Vienna’s main gallery streets, in part to show the collection.

Yet a recent article by critic Matthias Dusini in the left-wing Viennese newspaper Falter reveals that the image on the cover of the most recent exhibition catalogue, an abstract painting by Muehl showing two oval abstract forms, has a dubious back story. Dusini cites Ida Clay, a former communard, explaining that the ovals were made from the cheeks of a then 13-year-old girl’s bottom, forcibly held against the canvas.

While there is nothing inherently wrong with notion of uniting art and life, in the case of Muehl, his was far from the only life involved. According to the article in Falter, former communard Paul-Julien Robert has requested that a portion of the profits from sold artworks go to those who in part took part in their making (Muehl considered the commune an artwork, arguably making the people there his material)—not only those still affiliated with the estate.

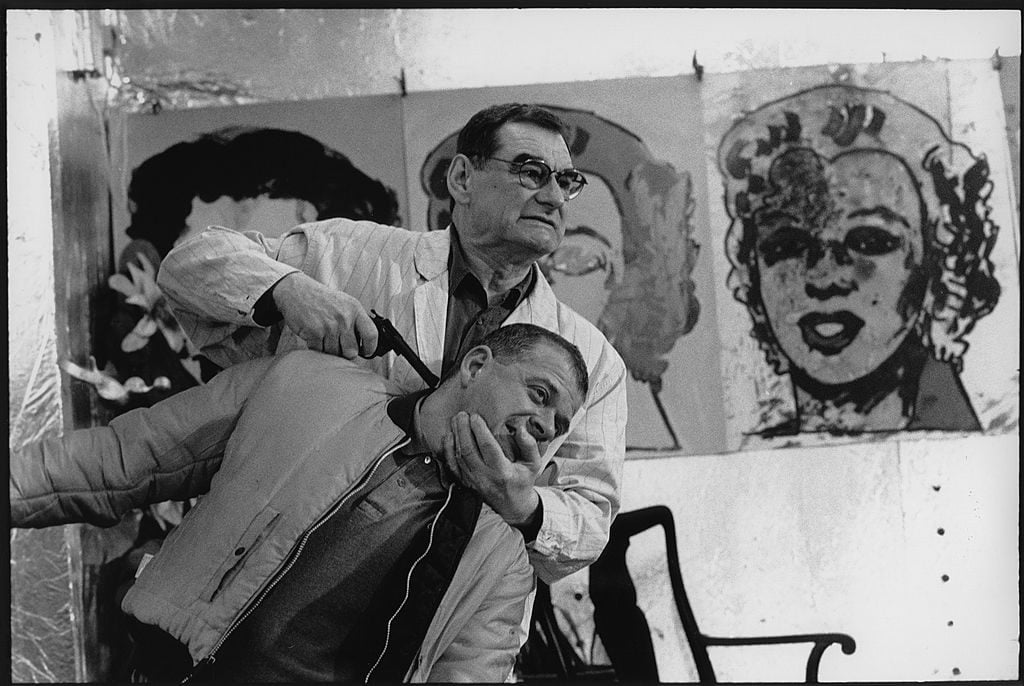

Artist Otto Muehl and art collector Erich Joham in the studio of the artist, circa 1991. Friedrichshof. Zurndorf. Burgenland. Photo by Imagno/Getty Images.

Before I read about what had happened to the 13-year-old girl, I’d spoken to Klocker, who is of course well aware of the issues at stake. “There are two arguments in favor of Muehl,” he said. “One is that an open, liberal democratic society should have the strength and maturity to not censor this work, but also to discuss it. And in my opinion Muehl is one of the most interesting and complex artists of the Second Austrian Republic in terms of both Actionism and his painting oeuvre in general. So many artists—Martin Kippenberger, Mike Kelley, Albert Oehlen—oriented themselves on him.”

“We won’t be able to solve the problem of Muehl,” dealer Ebi Kohlbacher told me. Until the end of February, his Vienna gallery, W+K, is hosting a show of Muehl’s work produced in the 1980s at the commune, a wild mix of styles in which Muehl quotes historical artists like Vincent van Gogh and Pablo Picasso (works there range between €5,000 and €250,000).

Another show, at Konzett gallery, titled “The Sins of the Fathers,” shows late works that Muehl made in prison and in Portugal. Austrians generally know of Muehl’s past (and some collectors boycott his works for this reason, according to Kohlbacher), but documentation of a 2015 show of Muehl’s work in Oslo, curated by Bjarne Melgaard, makes no mention of the artist’s crimes. Rather, it compares him to Francis Picabia and simply labels him a “bad boy.”

“The Sins of the Fathers“ at Konzett focuses on works that Otto Muehl created during his imprisonment in Austria from 1991 to 1998 and his time in Portugal from 1998 until his death in 2013. Courtesy Galerie Konzett.

The Fraught Present

In late 2020, Vienna’s Belvedere Museum director Stella Rollig made a public statement that the museum would not exhibit Muehl’s work for the time being, preferring to use its platform to give voice to others. It’s an interesting position that I read not as censorship, but as putting the Muehl question on the back-burner. Rollig rightly claims that any exhibition of the artist demands a deep ethical discourse (in the statement it’s clear that she also does not see the genius in his largely collaborative oeuvre).

Schroeder-Rozelle, the former communard, rather wants the abuses and crimes to remain known. “I’m not opposed to showing Muehl’s work: landscapes, politicians—whatever. That is important in a democratic and free society. But I am absolutely and categorically against exhibiting the works showing nude minors whom Muehl sexually abused,” he told me. “These works should never be bought or sold or shown in exhibits.” He has been successful in changing the title of a 2004 Muehl exhibition at the MAK, and wall texts in museums like the Centre Pompidou have been lengthened to include context.

Kettenraucher Mao (1968). Courtesy Estate Otto Muehl.

Another group, called Mathilda, has emerged from the second generation of children born into or taken to the commune, most of whom are now between 35 and 45. For many of them, including Ida Clay, Muehl’s abuse should not be neutralized or normalized as time passes. Understandable and necessary, but how does this play out in art-world practice?

In 2019, Klocker organized “Otto Muehl, Works 1955–2013,” a retrospective in Friedrichshof and Vienna. For the finissage, members of the Mathilda group added interventions and explanations to some works. Such an interaction is certainly a positive and appropriate step. Only those who were present, naturally, might be able to identify the conditions behind the production of the works in question—whether abuse was involved, or whether a victim is depicted.

But such measures don’t always work. In late 2019, the Dorotheum auction house in Vienna issued an apology for reselling a Muehl painting for €90,000 that depicted a young communard. Images of this and another sales have been removed from the house’s website. This is precisely where Schroeder-Rozelle takes issue: “These women are demeaned and feel continually abused through the public auctioning and exhibition of their abuse. It’s important for everyone involved to be aware of what went on.”

Some members of the younger generation are grappling with the trauma in different ways. There is Paul-Julien Robert, born at Friedrichshof in 1979 and who now lives in Vienna. His 2012 film My Fathers, My Mother, and Me is a heart-wrenching documentary in which he, on camera, dives into his childhood on the commune and confronts his mother, who joined Friedrichshof in her 20s. Robert visits former communards of his generation and all his living “fathers,” including Theo Altenberg, a Berlin artist who long lived in Friedrichshof and has since written reviews on Muehl’s exhibitions for publications like Frieze.

Installation view from “Otto Muehl: Works (1955-2013)” curated by Hubert Klocker. © Archives Otto Muehl, Sammlung Friedrichshof und Estate Otto Muehl.

There’s also Jeanne Tremsal, a Berlin restaurateur who lived in Friedrichshof as a child. She and the artist and film director Christopher Roth have made a feature film called Servus Papa, See You in Hell, based on her experiences, which is set to be released this summer. The film is the first feature to take on the Friedrichshof subject from a child’s point of view. (The 2009 documentary The Children Of The Commune also covers this generation, but from an adult perspective.)

“We all process having grown up on the commune in different ways,” Tremsal told me while she was installing a group exhibition in Berlin featuring her former communard father Benoit Tremsal’s sculptures alongside works by other artists including Roth, Isa Melsheimer, and Albert Oehlen. “It wasn’t only bad there. In fact, as a young child it was paradise: art, music, horses, the outdoors. But it became authoritarian and hell. The film is fiction, but it is my story, and there were moments writing it and shooting it when so much came up.”

Tremsal’s diary, too, was burned and made into Muehl’s art.