People

Behind Artist Allison Zuckerman’s Rapid Rise From Gallery Assistant to the Rubell Family’s Newest Obsession

The 27-year-old artist may be the brightest—and fastest—rising star at this year's Art Basel Miami Beach.

The 27-year-old artist may be the brightest—and fastest—rising star at this year's Art Basel Miami Beach.

Taylor Dafoe

A year ago, artist Allison Zuckerman was 26, fresh out of grad school, and frustrated. She was working for a gallery in SoHo and painting in her free time, but she wasn’t showing anywhere. So she began posting her work to Instagram instead.

“I would recycle old work—things that I had done in grad school or college—and then Photoshop it, turn it into new compositions,” Zuckerman recalls. “I felt like, ‘What am I going to do, carry my work through the galleries in Chelsea and say please look?’ The only way that people are going to see my work is through Instagram.”

Her strategy paid off. Tomorrow, Zuckerman opens her first solo museum show at the influential Rubell Family Collection in Miami, dedicated to the holdings of mega-collectors Don and Mera Rubell. It is a gig any young artist would kill for: The museum attracts hundreds of high-profile visitors from all over the world during this week’s Art Basel in Miami Beach. Her exhibition, “Stranger in Paradise” (December 6–August 28), includes 10 massive paintings she created for the space during a residency at the museum earlier this year.

Just a few months before that, however, she had absolutely no idea who the Rubells were.

Allison Zuckerman at the Rubell Family Collection in the summer of 2017. Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery and the Rubell Family Collection.

Born in 1990 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Zuckerman began painting when she was four or five. She signed up for art lessons to follow in the footsteps of her older sister and credits after-school classes with turning her into the art history junkie she is today.

Shortly after getting her MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2015, Zuckerman moved to New York—but a life as a professional artist seemed out of reach, and her family was getting impatient.

“As I was getting ready to graduate, my mom just started calling galleries in Chicago and saying, ‘Look at my daughter’s work.’ I was like, ‘Mom, you have to stop. You’re going to get me blacklisted,’” Zuckerman told artnet News on a recent November afternoon in her Bushwick studio, surrounded by new paintings about to be shipped to Miami for her solo booth with Kravets Wehby Gallery at the Untitled art fair.

Zuckerman, 27, radiates a Midwestern sensibility—warm, unassuming, and approachable. She wraps her mouth around drawn-out vowels. Her studio, meanwhile, resembles the artwork in it: frenetic and busy, with no wall unused.

A couple of months after Zuckerman began regularly posting her work to Instagram—when she was still working in SoHo and painting on an easel in the corner of her one-bedroom apartment in Williamsburg—the dealer Marc Wehby sent her a direct message to arrange a studio visit.

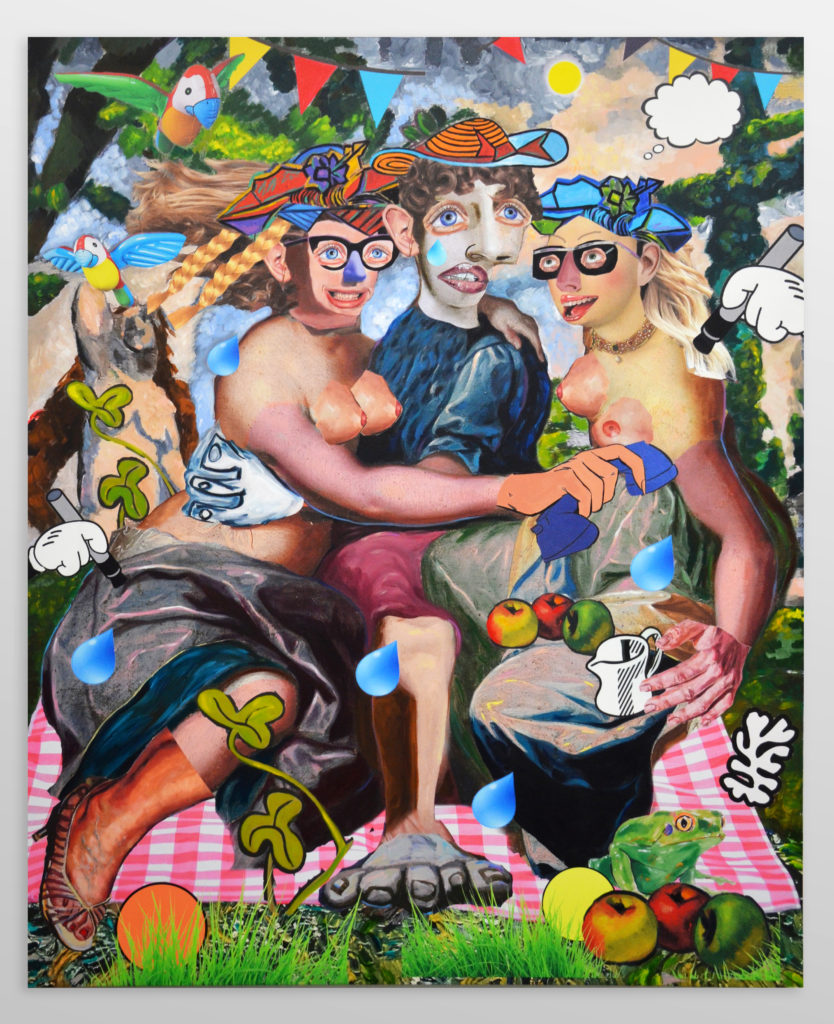

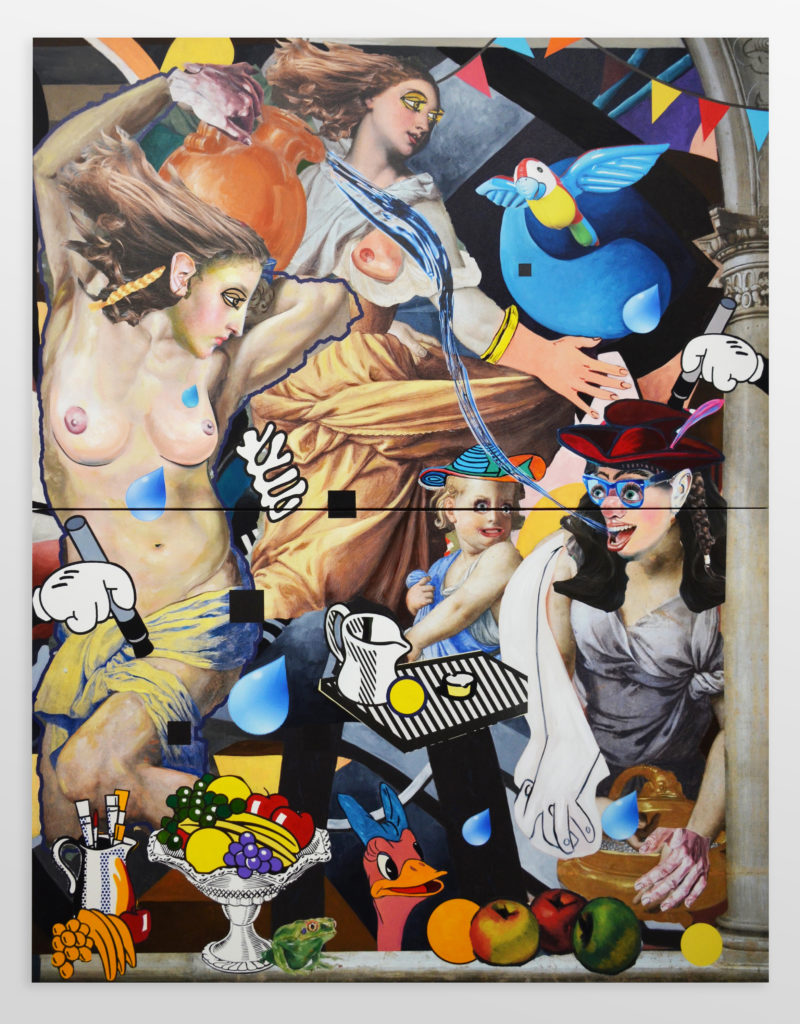

It’s not hard to see what piqued his interest. Her paintings are, in a way, destined to look good online; they begin as digital collages. She cuts out pieces of images, many of which are pictures of famous paintings, and then arranges the pieces in Photoshop, prints them on canvas, and paints atop them. Sometimes, she chops up images of her own works and uses them in later compositions. The results are part collage and part painting, perfect for our Internet-addled, distraction-filled age.

After the studio visit, Wehby offered to put three of her works—standalone collages printed on aluminum as thick as an iPhone—in an upcoming group show. That’s when things really started to take off.

Allison Zuckerman, Lunch in the Park (2017). Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery.

On a freezing day in January, a couple of weeks after the Kravets Wehby show opened, Marc and his wife Susan, who co-runs the gallery, invited Zuckerman over for lunch. She took the day off from her gallery day job to go. “I was really nervous, hoping they weren’t regretting showing my work,” she recalls. “I just wanted to make a good impression.”

As she was getting ready to leave, a couple she didn’t recognize walked in. “I didn’t want to get in the way, so I kind of took my cue and left,” she says. Five minutes later, Susan called and asked her to come back. The collectors wanted to talk to her.

Over the course of the next hour, she showed them her paintings and walked them through her Instagram account. “And then the woman says, ‘Alright, let’s go to the studio.’”

The studio, of course, was her apartment. And she wasn’t expecting guests. “I had been in a rush to get to lunch and left stuff all over the apartment,” says Zuckerman. “I had dirty dishes out.” She convinced them to give her a 20-minute head start and zipped around the room hanging paintings on the wall and taking sculptures out from behind her couch. She stashed the dishes under the bed.

After she left the gallery, Marc Wehby texted her.

“He asked me, ‘Do you know who that was?’” said Zuckerman. “I didn’t know. ‘Really nice art collectors?’ I said.”

“No, that was the Rubells.”

Allison Zuckerman, Manna (2017). Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery.

Don and Mera Rubell are two of most influential art patrons in the world. They founded the Rubell Family Collection (RFC) in 1964, and in 1993 created a 45,000-square-foot museum for their holdings in Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood. They have a reputation for spotting artists bound for major market success early on in their careers and acquiring a large portion of their output before they make it big.

They’ve visited their fair share of young artists’ studios in their time, but Zuckerman’s space stuck out.

“We barely fit,” Mera Rubell tells artnet News. “The place was packed. It was like walking into the 20-year career of someone who was working all the time and never selling anything. There were several hundred works of art.”

That day, the Rubells bought 22 pieces, as well as two of the sculptures in the Kravets Wehby show. For a while, they kept the purchases quiet. “Usually, we’re very happy to share our discoveries with everybody,” Rubell says. “But this time, we thought people were going to say, ‘What, are you crazy?’ These paintings are like candy. We were almost embarrassed to love them because they’re so easy to like. But then when you dig into the work, and you spend time with Allison, you understand that it’s extremely sophisticated.”

Allison Zuckerman, Bucolic Morning (2017). Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery.

A few months after her encounter with the Rubells, Zuckerman quit her job and had her first solo show with Kravets Wehby. (She also rented a studio in Bushwick.)

The Rubells offered her the residency in June. She stayed in their home for all of July and August and turned the main room of the museum into her personal studio, making 10 large paintings (some up to 16 feet tall) and a sculpture. The Rubell Collection acquired all of them before they were even complete; they now form the foundation for her show.

Zuckerman follows in the footsteps of previous residents Lucy Dodd, Cy Gavin, Sônia Gomes, and—most notably—Oscar Murillo, whose own turn at the RFC launched his rapid rise to art-world fame. However, Zuckerman—who is the same age that Murillo was then—shakes off the comparison, noting the difference in their work and her close relationship with her gallery, which she doesn’t think will end anytime soon.

Indeed, Zuckerman’s trajectory was slightly more common just a few years ago, when work by Murillo and other so-called “Zombie Formalists” was being traded back and forth for six-figure sums. In today’s slightly less frothy period, her ascent—which would be extraordinary at any time—stands out even more.

“In the 21 years that I’ve owned this gallery, I don’t think that I’ve ever had such diverse interest in a young artist,” Wehby says. “It’s come from all over the globe—British collectors and museums in Ohio and foundations in Mexico City, and on and on.”

Allison Zuckerman at the Rubell Family Collection in the summer of 2017. Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery and the Rubell Family Collection.

The title of Zuckerman’s exhibition, “Stranger in Paradise,” is a fitting description of her whirlwind rise to art-world prominence. It’s also a useful point of entry into her work. The phrase is sourced from a song of the same name, which originally appeared in the musical Kismet and has since been covered by Johnny Mathis, Tony Bennett, and Lady Gaga—a suitable metaphor for the appropriation and transliteration at the core of her practice.

And the cheap commodification of paradise is a theme that appears in many of her works. Consider the inflatable parrot that pops up in multiple paintings—partly a reference to Jeff Koons, it looks like it was culled from a Jimmy Buffett concert.

Allison Zuckerman at the Rubell Family Collection. Courtesy of Kravets Wehby Gallery and the Rubell Family Collection.

Her juxtaposition of colorful pop imagery with art historical references recalls other young artists working today, such as Jamian Juliano-Villani, Marc Horowitz, and photographer Daniel Gordon. But her approach feels more musical in nature: a mash-up or hip-hop track that samples and layers multiple songs, often without the permission of their creator.

“For me it evokes the idea that we are living in an age where everything is out there and you can post and repost someone’s photo,” Zuckerman says. “It’s like the Wild West.”

Her source material ranges from Old Master portraits to emojis. But the fragments cribbed from art history—notably, all work by men—tend to dominate the compositions. It is difficult to tell whether the citations are homages or critiques.

Zuckerman says the answer lies somewhere in the middle. “It’s like I’m inviting them to the party, but then roasting them at the same time,” she says. “There’s no denying the contributions and significance of these artists; it’s about pointing out the inequalities that they have benefited from—unintentionally or intentionally. There’s a level of admiration that I definitely feel, but it’s also about saying, ‘Well, you’re not going to get away with it anymore.’”

“Allison Zuckerman: Stranger in Paradise” is on view at the Rubell Family Collection through August 25, 2018. Her work will also be featured at Kravets Wehby’s booth at Untitled Miami Beach, which runs from December 6–10 at the intersection of Ocean Drive and 12th Street in South Beach.