Art & Exhibitions

Once Toiling Behind the Iron Curtain, Hungary’s Radical Women Artists Are Finally Getting the Recognition They Deserve

Artists who refused to conform during the Communist era are emerging now in their 80s and 90s.

Artists who refused to conform during the Communist era are emerging now in their 80s and 90s.

Javier Pes

Gaps had appeared in the Iron Curtain separating Hungary’s avant-garde artists from the West by the late 1960s, and the artists were quick to exploit them. When the Berlin Wall fell, however, artists who refused to conform to whatever style was in official favor during the 1960s and ’70s did not get the international recognition they deserve—until now.

Today, museums and collectors are beginning to take note of a number of the women from this period, several of whom are still going strong in their 80s and 90s. “It’s been a long time coming,” says New York-based writer and researcher András Szántó, who curated an exhibition of work by artists who refused to toe the official Communist Party line at Elizabeth Dee Gallery in New York this past spring and an ambitious non-selling show in London during Frieze week.

Most of the artists, female and male, were tolerated rather than banned by the authorities, Szántó says, often playing a “game of cat-and-mouse” with the state. While this was not the “gulag-era of Soviet times” after the failed Hungarian uprising of 1956, he says their independent spirit and nonconformity was risky. “A few spent unpleasant evenings with the secret police,” he says.

Among those now emerging on the international stage is the 84-year-old artist Ilona Keserű. She had her first solo show in London this spring at Stephen Friedman Gallery, following her inclusion at Frieze Masters in 2017. In December, her work will hang alongside that of Jackson Pollock and Carmen Herrera, among others, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Epic Abstraction” show.

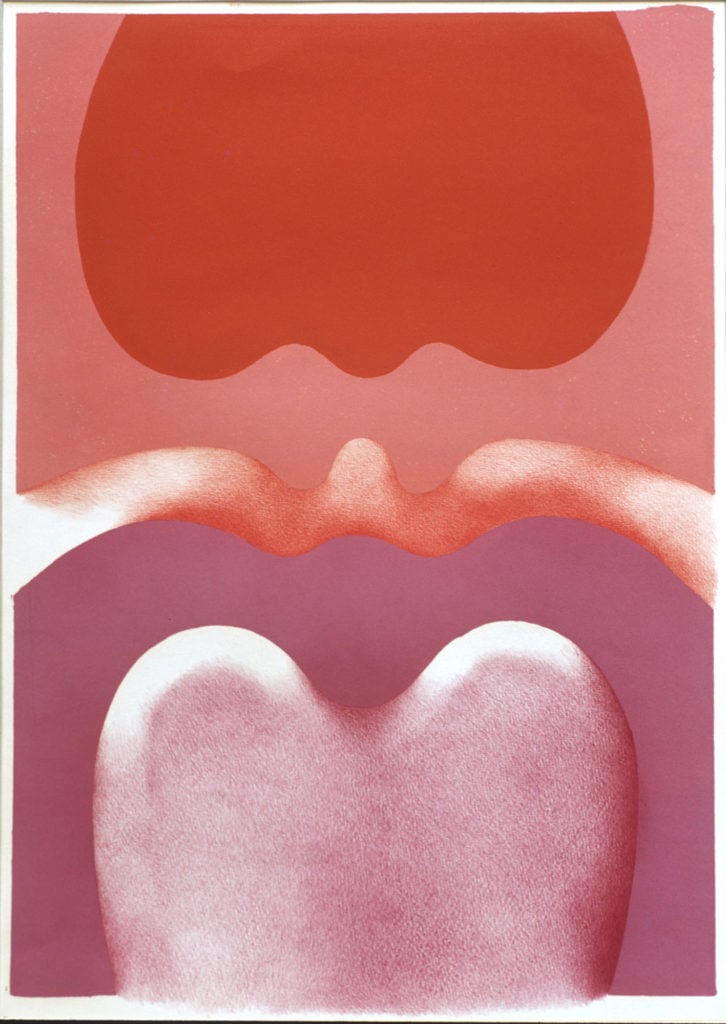

Last year, the Met purchased Keserű’s vibrant 1969 textile piece Wall-Hanging with Tombstone Forms (Tapestry). It was inspired by the heart-shaped tombstones she saw in a cemetery, a motif that would often recur in her textile works and paintings.

Keserű was able to see the work of other abstract artists when she traveled within the Eastern Bloc. In 1962 she got a visa to go to Italy, which was a turning point. There she saw work by Western artists, including Cy Twombly’s canvases and Albert Burri’s sack paintings.

Szántó says audiences in the West are often surprised at how well informed Hungarian artists were about developments in international art on the other side of the Iron Curtain. “They were paying attention,” he says, and some could visit exhibitions such as documenta. With no state support or opportunity to make a living by their art, they made work that has a “lot of credibility,” he says. Much of their art also resonates today as authoritarianism rises around the world, he adds.

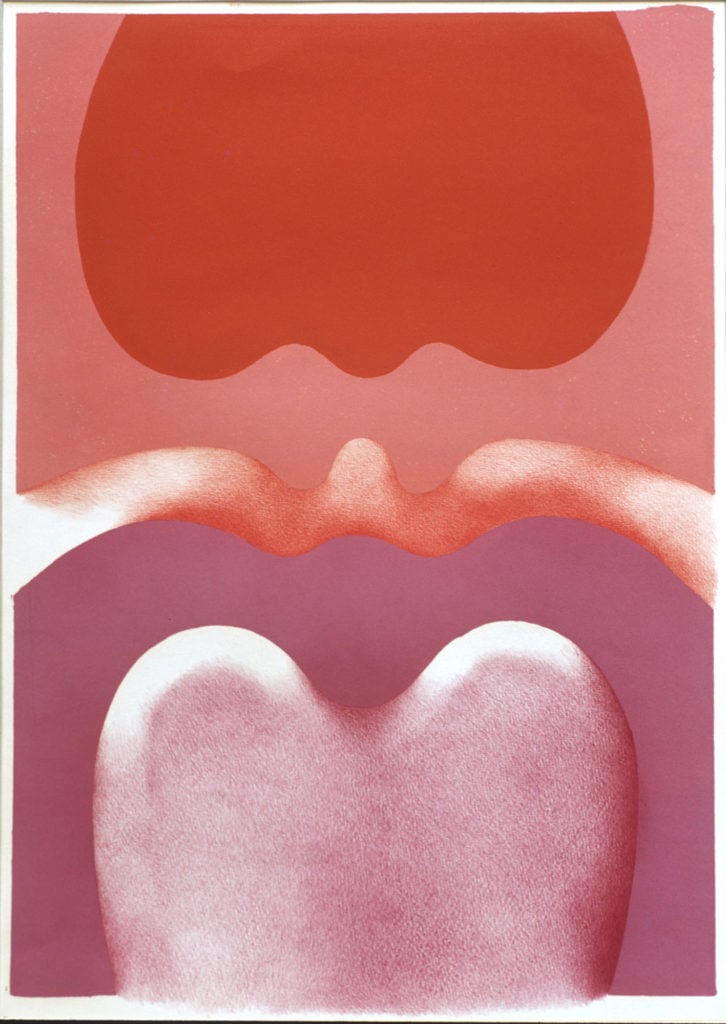

Katalin Ladik, Blackshave Poem (1979). Photo by György Galántai, courtesy of the artist and acb Gallery.

Katalin Ladik (born in 1942) is another veteran artist from Hungary who is belatedly being recognized internationally. Szántó compares Keserű and Ladik’s emergence later in life to the “Carmen Herrera narrative,” referring to the Cuban-American artist who created work for decades before she was rediscovered in her late 80s. Last year, Ladik took part in documenta 14.

Ladik’s five-decade multidisciplinary practice is closer in spirit, however, to an artist like the American feminist Hannah Wilke. Born in an area of the former Yugoslavia inhabited by many Hungarians, Ladik began her career at the same time as Marina Abramović did in Belgrade. A poet and musician, Ladik first created happenings, body art, and performative pieces in the late 1960s.

This was a time in Hungary when simply being an abstract artist challenged the status quo. Ladik’s radical, gender-bending performances could not have been further from the uniformity demanded by the Hungarian state. “I was bi-gender and androgynous,” she told the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in a recent interview for the new book “Bookmarks: Revisiting Hungarian Artists of the 1960s and 1970s,” which Szántó co-edited with Katalin Székely. Ladik staged a performance at the book’s launch in October at the Vinyl Factory.

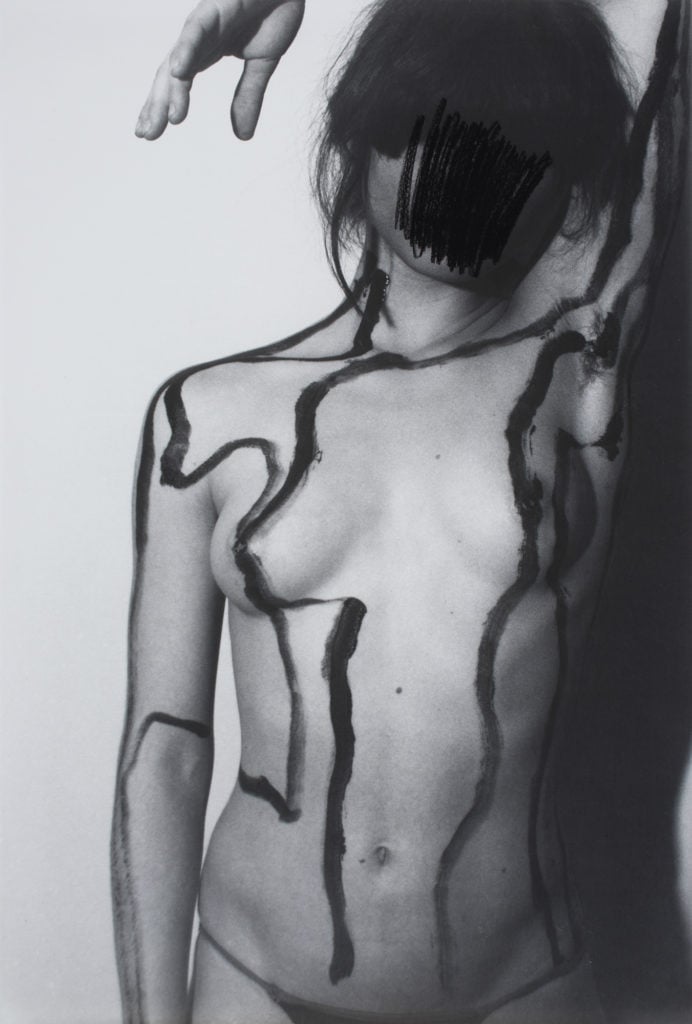

Dóra Maurer, who was born in 1937, also refused to produce official art that would have brought state support and all manner of “goodies,” Szántó says. She escaped the dead hand of totalitarianism by being largely based in Vienna. “Maurer is an influential figure and role model,” he says, adding that she was also one of the most experimental, creating abstract works as well as avant-garde films, photographs, and environmental actions. She has also organized influential shows on her return to Budapest.

Dóra Maurer, Objectified Outline 1-7 (1981). Photo by András Bozsó, courtesy of the artist and Vintage Galéria.

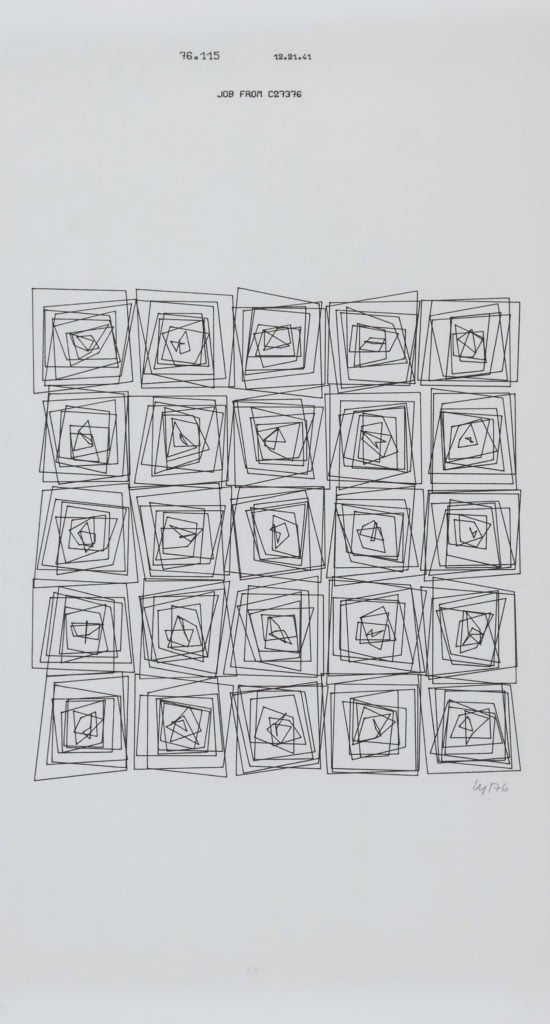

Vera Molnar, who is in her 90s, is still creating new works and completing previously unfinished projects. She is part of the Hungarian diaspora, having moved to Paris in 1947, where she met another Hungarian émigré, László Moholy-Nagy. A pioneer of computer art, Molnar told Ulrich Obrist that in 1968 in Paris, she thought “everything was possible.” So, she knocked on the door of the computing center at a Paris university.

Initially she thought the man in charge was going to call someone to get her locked up, she recalled. Bemused to find a foreign female artist on his doorstep, he invited her in. (He later told her he remembered Voltaire’s famous quote about the need to defend someone’s right to do or say something even though you disagree with everything they say.) Molnar was able to use one of the few computers in France at the time. “It was very expensive, we had to rent [them] by the minute,” she recalled.

She went on to create her first computer drawings based on a series of geometric grids there. The Paris riots in May 1968 were a blessing. The students abandoned the mainframe computers to flock to the barricades. “I was alone at Orsay with a technician, a cleaning lady, and a coffee machine,” she said. “I got a lot done.”

Vera Molnar, from the series “Transformations of 10×10 Squares” (1976). Photo by András Bozsó, courtesy of the artist and Vintage Galéria.

“Bookmarks: Revisiting Hungarian Artists of the 1960s and 1970s,” edited by András Szántó and Katalin Székely, is published by Koenig Books.