Hunter Biden is on the move. The lawyer, former lobbyist, and son of U.S. President Joe Biden has left his $5.4 million rental in Venice Beach, California, for a quieter Los Angeles neighborhood up the coast. He won’t say where, exactly, because right-wing guys like to show up on his doorstep with bullhorns.

He’s 15 minutes late for our interview because the house doesn’t have mobile service yet. “I’m wondering how many people are trying to get in touch with me and then failing,” Biden, 51, told me over the phone. “Which is kind of nice actually. Usually, I just don’t answer the phone.”

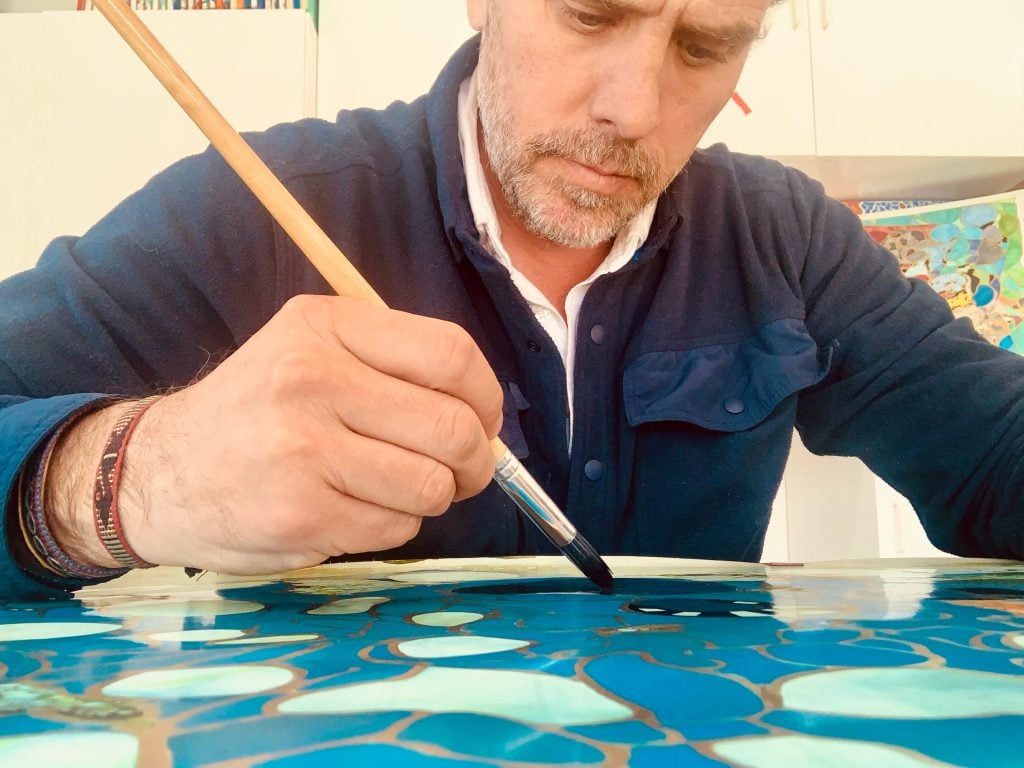

Hunter Biden, Untitled (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Georges Bergès Gallery.

The topic of our interview has nothing—and yet everything—to do with Biden’s well-documented struggle with addiction, his new memoir, his famous dad, his made-for-the-tabloids romantic life, or his ties to President Trump’s impeachment and to Ukraine. Nothing, because he wants to talk about the art he’s been making and his upcoming show in New York this fall. Everything, because, well, it’s art, and for Biden, everything is connected.

While he has no formal training, Biden has been making art since he was a child. In recent years, the practice has taken on a more formal, serious turn and he now works as an artist full-time. He has a dealer, Georges Bergès; a studio; and a collector base. A solo show is on the horizon. Bergès plans to host a private viewing for Biden in Los Angeles this fall, followed by an exhibition in New York. Prices range from $75,000 for works on paper to $500,000 for large-scale paintings, Bergès said.

In the new house, the studio occupies a converted three-car garage, with a brick floor and a skylight. Biden usually gets up at 5 a.m.—before his 14-month-old son Beau, named after his late brother, is awake—makes a cup of coffee, heads over to the studio, and stares at a blank canvas.

He typically paints on a tabletop, horizontally, and doesn’t “fully envision what it will become,” he said. “At least, it never turns out to be what I started off in my mind’s eye at the outset.”

Hunter Biden, Untitled (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Georges Bergès Gallery.

Working on canvas, metal, and Japanese Yupo paper, Biden’s artworks are often layered, with elements of photography, painting, collage, and poetry. Some are geometric abstractions, filled with patterns and somewhat hallucinogenic. Others depict trees, leaves, and body parts like outstretched arms.

“I don’t paint from emotion or feeling, which I think are both very ephemeral,” Biden said. “For me, painting is much more about kind of trying to bring forth what is, I think, the universal truth.”

It’s tempting to brush off a statement like this as a bunch of malarkey. But for Biden—a controversial figure who has been vilified by the right and uncomfortably ignored by the left—what is that universal truth, exactly?

Hunter Biden, 019 (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Georges Bergès Gallery.

“The universal truth is that everything is connected and that there’s something that goes far beyond what is our five senses and that connects us all,” he said. “The thing that really fascinates me is the connection between the macro and the micro, and how these patterns repeat themselves over and over.”

And indeed, patterns—some tragic and uncanny—are very much part of Biden’s life. The move to the new house has been complicated by the fact that Biden’s wife, Melissa Cohen, had to return to her native South Africa after her mother, who, at 72, succumbed to the same form of brain cancer as Biden’s late brother, Joseph Robinette “Beau” Biden III—six years and one day apart.

For Biden, who has been making art throughout his dad’s presidential campaign and the relentless scrutiny that accompanied it, creative expression is neither an escape nor a form of therapy. Although he told the New York Times last February that painting was what was “keeping him sane,” his motivations have become grander.

Hunter Biden, St. Thomas (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Georges Bergès Gallery.

Today, “it’s not a tool that I use to be able to, in any way, cope,” Biden said. “It comes from a much deeper place. If you stand in front of a Rothko, the things that he evokes go far beyond the pain that Rothko was experiencing in his personal life at that moment.”

Biden, who is drawn to abstracted figurative forms, is influenced by the pattern-based work of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung. He also loves artists Yayoi Kusama, Sean Scully, Mark Bradford, and David Hockney.

Bergès, Biden’s dealer, who operates galleries in New York and Berlin, was drawn to the honesty of Biden’s work. “It has that authenticity that I see in a lot of artists that I personally love, be it [Lucien] Freud or [Francis] Bacon,” he said. “A lot of the issues that are thrown at Hunter is what makes him produce really great work.”

Georges Bergès, who represents Biden.

Bergès—who represents a roster of international artists but is not a regular at art fairs or a typical stop on the blue-chip gallery circuit—said he has been a constant presence in Biden’s life over the past year. The two speak by phone as many as five times a day. “I’ve encouraged him to incorporate his written work in his photo-based mixed media,” Bergès said.

One such work is Biden’s self-portrait, which took two years to complete. He’s depicted as a silhouette, filled with colorful patterns that evoke sea organisms seen through a microscope. Behind him is the arc of a hill and a red disk in the sky. Looking closer, you see a few cursive lines of poetry, scribbled in gold on red:

All around him

beautiful things

tangled colors

cradled mercy

made real

rose up

and he began again

to write

a new story.

The poem is related to Biden’s book, Beautiful Things: A Memoir, published in April by an imprint of Simon and Schuster, but, of course, there’s a deeper meaning.

Hunter Biden, Untitled (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Georges Bergès Gallery.

During the last six months of his brother’s life, Beau started to lose the capacity to speak, Biden recalled.

“One shorthand that he would use with me was he would say, ‘beautiful things, beautiful things.’ And it was a way for us to each tell each other to stay focused on the beautiful things in front of us. And the first beautiful thing in front of me was my brother.”

In turn, he said, for his brother, the phrase was also a testament “to the beautiful things that he thought my art was.”

It’s time to wrap up our call, but one final question must be asked: What does his dad think about his art?

“My dad loves everything that I do, and so,” Biden said, “I’ll leave it at that.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.