Bernie Chase is an unorthodox, unconventional art-world inhabitant. To put it mildly. At 65, he dresses as age-inappropriately as I do, but wears it better. He operates a few contemporary art galleries on West Broadway in New York City, mostly in the street art vein (but not entirely), dealing in the work of such artists as Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, Richard Hambleton, R. Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, and Robert Williams. You won’t see Bernie exhibiting at the Frieze, Basel, or Armory Show art fairs, or even trying to. But that’s a good thing—he’s among the least pretentious, most honest art dealers who ever dealt art, transparent to a fault. And in today’s social-climbing, too-cool-for-school, duplicitous art world, those are very endearing traits indeed.

Having started out in the classic car trade, with a stint in federal prison for institutionally scaled marijuana dealing in the 1970s, Chase cut his dealing teeth on objects from chopped cars to rugs covered in precious stones brokered to and from Prince Jefri Bolkiah ibni Omar Ali Saifuddien III, a member of the Brunei Royal Family. You couldn’t make it up and I didn’t: I interviewed the man himself a few weeks ago about his rollicking life story. Buckle up and enjoy.

Kenny Schachter: You almost were run over by a car the other night when we were speaking outside my kid Adrian’s opening at Gratin Gallery.

Bernie Chase: Yeah. They’ve almost killed me 100 times. I’ve been hit a couple of times by cars at art fairs or openings, because everybody’s always in the street. A cab hit me at Art Basel.

KS: Remind me not to stand near you. Alright. Tell me about R. Crumb.

BC: There was a guy named Jimmy Brucker and he had a hangar at the San Palo airport up in Northern California. He was a patron of Robert Crumb. He also had a lot of Rick Griffin; he had the whole body of works by Von Dutch, and Robert Williams; he had S. Clay Wilson, hundreds to thousands of pieces of art. He was just a guy in the art world, and a big car collector in the ’80s and ’90s.

At the time, I was still a partner with RM auctions—it was before Sotheby’s bought it. The Bruckers wanted to sell a bunch of their car collection, and at that time, all the art they had was quite in vogue. We decided to do a street art-type auction, to be held at the Petersen Automotive Museum. This was in the ’90s, or the early 2000s, one of the two. I went up there to make the deal with the Bruckers, and I made a deal with them for a good-sized catalog, but Robert Crumb really didn’t fit into the program. I think there were, like, 600 pieces of R. Crumb work.

I kept going back and forth and back and forth to San Paulo, out to the airport to go through the inventory, and figure out what was going to go into the auction, and to go through the cars that they had that were going to go on the auction. The R. Crumb work wasn’t actually owned by them; they were just the caretaker of it. It was owned by kind of a funny guy in Orange County. Around the same time as this, I had acquired this giant body of work from Ed “Big Daddy” Roth. The person that was the owner of the Robert Crumb took my big body of Big Daddy Roth, and I gave them money and bought the R. Crumb collection. I just had a good feeling about it. I liked it. I liked the art. I knew a couple people on the market that were buying Robert Crumb. They were always following the market, they were paying a lot, and outbidding me on certain pieces.

After I bought it, I made a deal with Mark Parker, who was at the time, I think, the CEO of Nike. I think he’s now the CEO of some part of Disney [he’s chairman of the Walt Disney Company]. I sold some of the body work to Mark Parker after I got it. Then for years, I filtered a bunch of the work to Heritage Auctions, and consigned it to different galleries and slowly but surely worked my way out of the project. I kept the pieces that I really liked, and eventually sold some of them—a couple to you. I personally didn’t ever meet R. Crumb, but I paid for him to come to California and look at the whole collection to verify everything was by his hand, and to see if he saw any things that didn’t register, or to say “I’m uncomfortable with this piece.” So he came, looked at everything, and gave us his blessing. Then after that, we sold it.

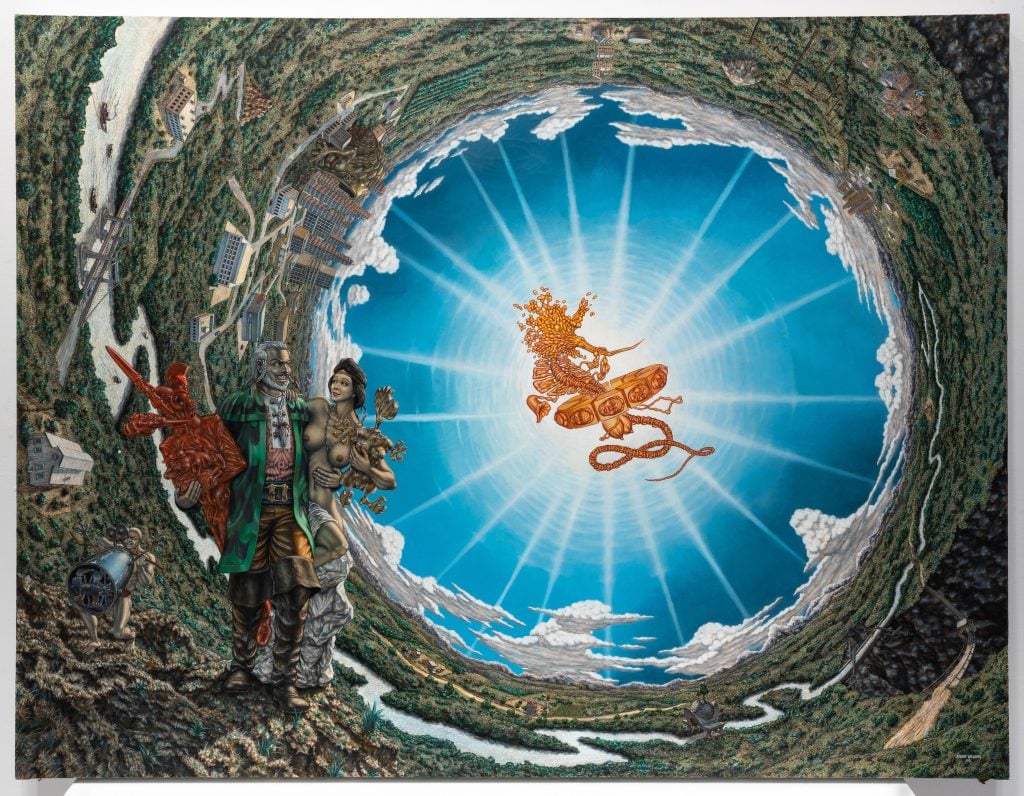

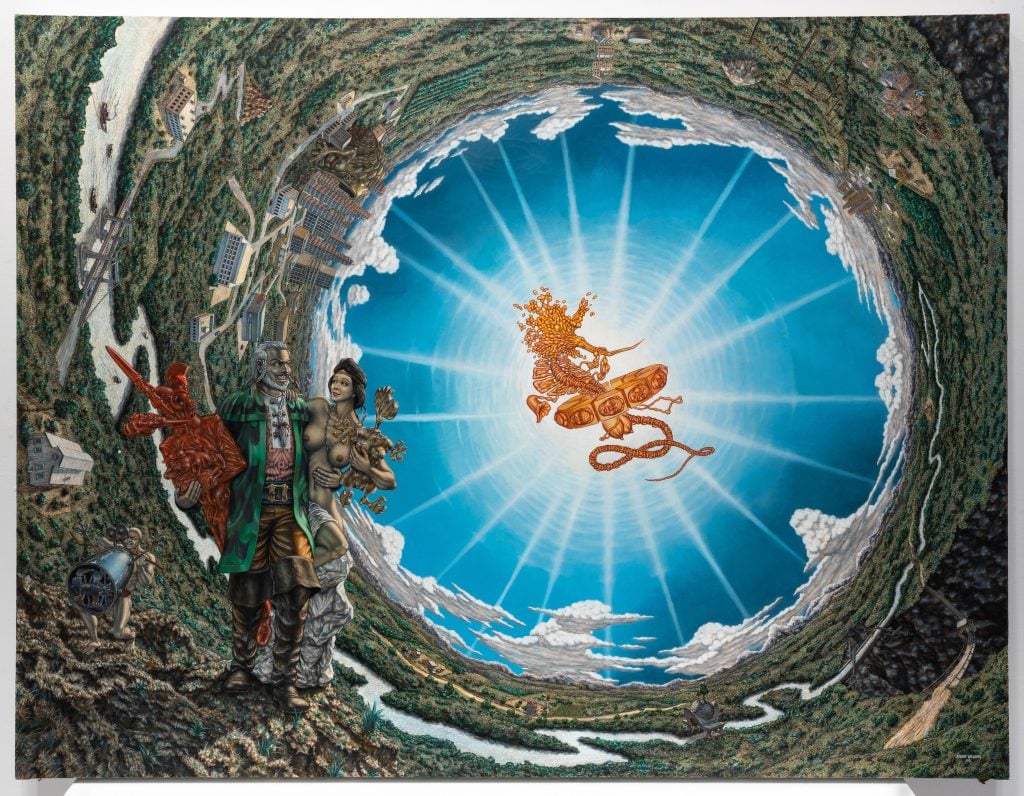

Robert Williams, Psychic Pedestrians on a Spiral Horizon (1982). Photo: © Robert Williams.

KS: I see. How did you first get into art?

BC: I’ve always liked art. When I was young, I always had fantasies of being a treasure hunter, for some reason. So I played around with buying different kinds of art. I really liked Old Masters. I really liked 17th-century art. How I got into that was I was staying at the Dorchester Hotel and a guy came to my room and he’d just bought this painting, a Philips Wouwerman, a 16th-century Dutch piece. He bought it from Richard Green, and he told me that Richard Green had other Philips Wouwermans in stock.

It was Sunday and I walked over on Bond Street—Richard Green had two stores, one on Bond Street and one on Dover. In the window, there was this beautiful giant copper painting. I didn’t know who the artist was, I had no idea. They were closed on Sunday. So on Monday I came back and the painting was a Franz Christoph Janneck, and it was an 18th-century Austrian painting. Then I dealt with Richard Green’s son, Johnny Green. We just started chatting and I said, “I like the painting the window. I don’t know much about any of this art, I don’t know the value, but I am interested in buying some stuff, and I won’t waste your time, I promise.”

I make decisions pretty quick—not always the best decisions, but I make decisions. We spent three or four hours together, and we went to all the stores. I picked eight pieces of art I liked from the 16th century to the 19th century. They told me the prices they wanted, so we talked and we became friendly. They had a big lunch room in their place, downstairs, where they ate every day. It was kind of a ritual, and I started coming there for lunch; it was really nice. You’d go downstairs, and they had a private chef, and you’d sit down with the family and all have lunch together.

We started talking about the deal and I said: “The only thing that I feel comfortable with, the only way that I can do a deal with you, if you want to do a deal today is this: I’ll buy the pieces that I like all from your galleries, all from your company, but only if you produce all your receipts. I’ll give you 15 percent over what you bought, across the board. This is not knowing if you bought too high, not knowing if you bought it in a ring with a bunch of guys, not knowing any of the facts. That’s the only way I can make a logical decision. Just prove to me that’s how much you paid. If I find out later that those aren’t the numbers, there’ll be a penalty clause in there.” They said, “Oh, that’s crazy. We can’t do business that way.” And I said, “Okay, well, if you want to start doing business with me, that’s the only business deal I’ll do. I’m not going to buy things if I don’t know the value.”

They asked me to come back in a couple hours. When I came back, they had all their receipts out, and we made the deal. I bought all the pieces, and I sold them all probably within a year or so, mostly through the auction system. I did really well on everything. Fifty percent of the pieces, they bought back from me.

Then I met Johnny van Heffan and McConnell Mason. I met all these guys in that area. Christie’s was on one side of town, Sotheby’s on the other, and all these galleries were in the middle. I would just pop into all the galleries and try to make the same deal with everybody. I was having fun, and trying to understand the value of the stuff because I didn’t really like contemporary art.

Then there was the Thomas Mellon Evans sale, the banking family. A single owner sale. By then, I knew all the dealers a little bit. The way that I continued to buy paintings was, I would just sit at the back of the salesroom, and I would be a phone bidder to the phone bank, but I’d be bidding in the room, on my telephone. I was watching the dealers, I’d be watching what was going on, and I would make my decision. If I liked a piece, I would wait and see what the dealers were doing. Say Richard Green made a bid, and that was his last bid. It was going to go to him, then I’d make a bid, but he didn’t know who I was because I was on the telephone calling the phone banks. That’s how I started buying at auctions.

Maybe sometimes I made mistakes because that could have been their own merchandise for all I know, but the Mellon Evans sale was the Mellon Evans sale. One of the paintings that Green got, that I couldn’t get was a Lucas Cranach the Elder. After the sale, I bought it off them. I gave Richard 20 percent above what they paid. I remember I kept it for about five years, then I put it in an auction at Christie’s.

I didn’t know much about this at that time, but the historian that made the decision, about the period, the Younger, the Older school, or whatever you want to call it had passed. There was a new historian, a new guy that gets certifications. Christie’s came back to me and said, “Well, this isn’t the Elder.” I don’t remember if they said it was the Younger or it was the school, but I thought, well, I’ve been doing a lot of business with both the auction companies, I have a really good relationship with them. I was getting above the hammer, I was clawing back buyer’s premiums. I had that deal until just recently—I had that deal for 30 years.

KS: You stopped it?

BC: I haven’t stopped. I just don’t really buy that much from the auction companies. I would say in the last 24 months, I’ve done a lot of deals where I’ve clawed back part of the auction house’s commission. It’s just been part of my contract. I’ve never gotten 110 percent. I’d say 106 percent and maybe 108 percent—two percent to my lawyer, 106 percent to me. It’s not all the time, but it was a lot of time.

What happened was, I bought the work off Johnny Green, and Johnny Green bought it from Sotheby’s. So I went back to Johnny and I said, “Johnny, I want my money back.” It was five years later. And Johnny goes, “We bought it in good faith. It was in the catalog as the Elder and it’s just the luck of the draw sometimes.” And I said, “Well, I don’t feel that’s fair. Luck of the draw. You’re a gallerist.” They were really big at the time; they were the biggest dealer in London. And I said, “I think that you should give me my money back, or you should let me buy art at the same value as the number, and I’ll just take art.” They had a family meeting—they always used to have family meetings—and they traded me. The Greens always treated me with respect. They were always fair with me.

KS: Where’d you grow up, in California?

BC: I grew up in Gardena, and then from Gardena to the San Fernando Valley, and from the San Fernando Valley to Venice.

KS: What did your parents do?

BC: My dad was an accountant, a CPA. And my mother was a mother.

KS: Were you into art when you were a kid or younger?

BC: No, I wouldn’t say I was in art when I was younger. No, I got into liking cars at a young age, and bicycles, and fixing them. Art became something in my later teens that I started liking.

KS: What was your first business? Tell us about your experience in your first entrepreneurial enterprise.

BC: My first business, when I was young, was buying broken down cars and bicycles, and rebuilding cars and bicycles. My first major enterprise was buying from junkyards, buying broken Volkswagens, and taking maybe a lot of cars and building four cars out of it, and selling them. I did it with a couple of friends of mine. We were all pretty young—not at home anymore, and surviving. I was working my way into other kinds of cars from Volkswagens, went into Jeeps and from Jeeps, went into Mercedes lines, all the Mercedes lines, and then from there slowly but surely crept into the Ferrari world.

The first Ferrari I ever bought—the first time I was really like, “Okay, I’m gonna step into this world. I’m gonna buy a big Ferrari”—I bought a Boxer. It was an ‘81 carbureted Boxer. I bought it in Texas and brought it to California. I remember the price was, like, $35,000. It turned out to be stolen. My first step into the Ferrari world and I bought a stolen car. We dealt with the insurance company in Italy that had a claim on it. Over the years, it happened to us quite a bit: you’d buy a car and it’d be stolen from someplace in Europe or somewhere. Then you have to deal with the insurance company. It made it to Texas, and it was definitely a European car. There were no Boxers coming to America at the time. They were not even in 1984, when they discontinued the Boxer. It was still a gray market car. And then in ‘85, the Testarossa came in for the American market.

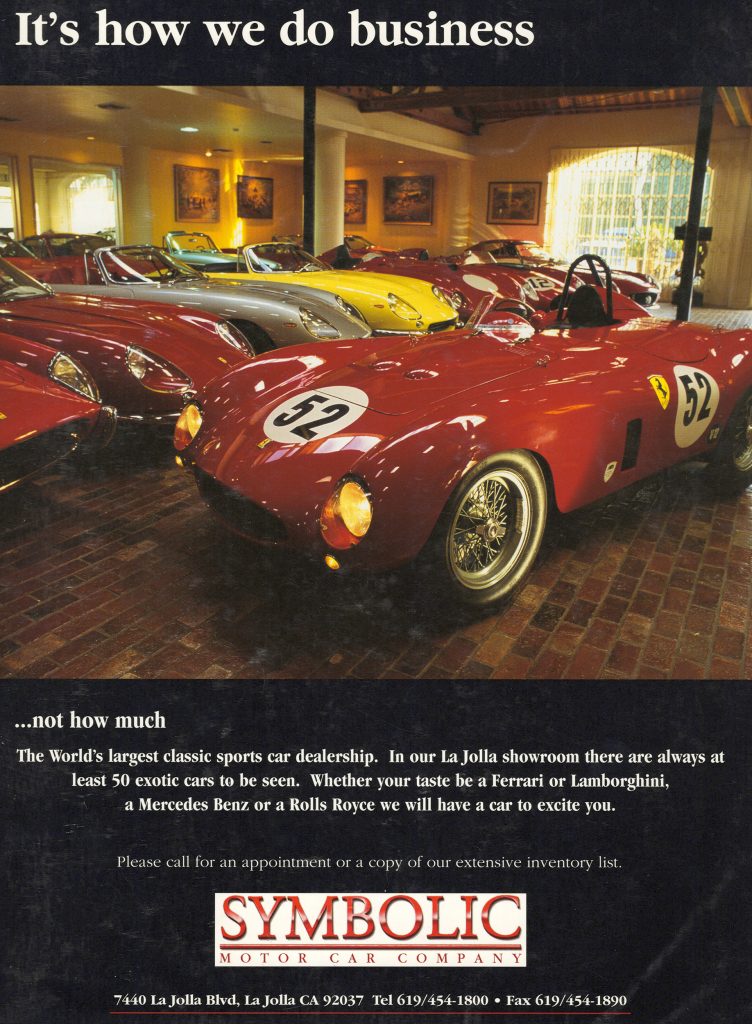

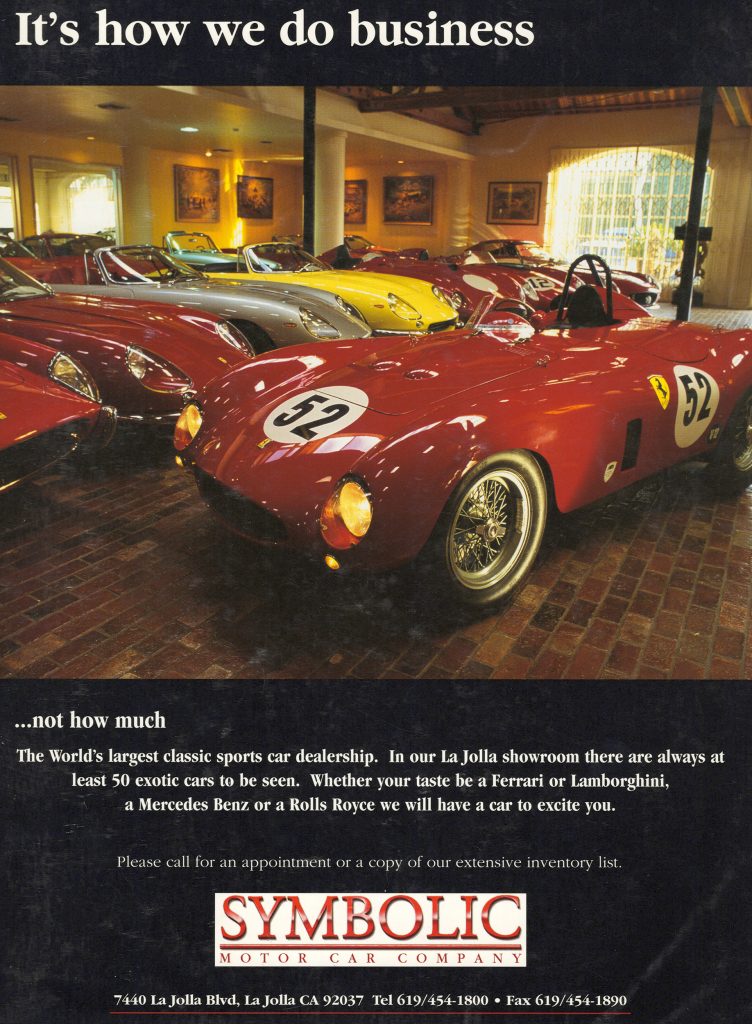

Photo courtesy of Bernie Chase.

KS: And you taught yourself about the whole Ferrari world?

BC: I was self-taught for the whole Ferrari thing. I had an older friend of mine that really liked Ferraris. He was kind of watching my career, and he had a bunch of Ferraris—three Ferraris, all in parts. He made a deal with me to be partners with him and restore the cars, and his cost of buying, and my cost of restoring them. We would be partners in the upside. It was kind of a hobby for him and he didn’t want to restore them all.

I had another friend that was really good at restoring Ferraris, and that was kind of my real entrance in the Ferrari world, because one of the cars was a 275GTB/4 NART Spider. The factory only made 10 of them. In theory, they made 11, but really 10. Steve McQueen had bought a few of them new. That car was a really interesting car in my life, because we restored it, then we sold it to a really interesting guy years later, a guy named John Moores in San Diego, who bought the San Diego Padres. And he had bought a couple of 275GTB/4 NART Spiders from me.

KS: It’s an aftermarket conversion, right? North American Racing Team? It’s not a factory.

BC: NART represented Ferrari in America. The factory built these cars, these coups, and these coups went to NART. Today, the last one that traded at auction went for $27 million, and I was in the room that day. The underbidder was the guy with John Collins, a company called Talacrest in London. The story is kind of interesting about that NART Spider because it was my entrance into the Ferrari world. Then it was my entrance into philanthropy. So the guy in San Diego, John Moores, he was from Houston. He was a tech guy who sold his company and moved to San Diego, and really helped the community. He bought the baseball team. He donated a lot of money to UCSD, something like $100 million. He also became quite a substantial collector of Ferraris. He only wanted the best of the best and at the time, they weren’t so expensive.

Photo courtesy of Bernie Chase.

KS: This was before Symbolic, your company?

BC: I had Vintage Motorcar Companies when John Moores bought the cars from me. It was a little place, a storefront I had from ‘86 to ‘91. It was on the beach, it was great. We had a pretty nice dealership. A lot of Ferraris and Lamborghinis, a lot of Maseratis, Ghibli Spiders, Daytona Spiders, Coups.

There’s a Scripps Institution in La Jolla. It’s on Torrey Pines, where the golf tournament is. It’s an institution, with hospitals and cancer centers and research centers. I wanted to build a Ferrari museum at Scripps Research, so I went to see Richard Lerner. He was then the chairman and CEO of Scripps Research. I went to see him with a business plan, and I said, “Look, we should build a Ferrari museum inside of Scripps Research, in your compound. I’ll get donations from everybody, we’ll build this great museum, and people can store their cars there, and we can start raising money for different kinds of research.” Well, they didn’t like that idea. Then I said, “Look, I want to raise money for an institution for neglected diseases. I really want to be involved in neglected diseases. I will raise money to build a facility. Let’s talk about it. I have enough customers to get this done.”

So then there’s an article in 1998, in Forbes magazine, in the issue where they talk about all the billionaires. As soon as that ends, the next page is a two-page article about Symbolic Motors, which me and my brother started in 1990. And it says, “Would you buy a car from these brothers?”

In that article, they interviewed people that don’t usually take an interview, right? Rob Walton was one of the people they mentioned that had bought cars from us. They talked about Sir Michael Kadoorie of China Gas and Electric buying cars from me. They talked about Ron Burkle buying cars from me. They talked about all these guys that were buying cars from us for millions and millions of dollars, when cars had never gone to that price ever. The article is about these young kids selling all these cars for these prices. People were telling me we were crazy for asking these prices. We didn’t know what we were doing, but it worked. People bought the cars. At the end of the article, it goes back to this project at Scripps. It talks about that, about Symbolic raising $60 million to build at Scripps, a research facility for childhood, genetic, and neglected diseases. My passion was to help children or people that are being neglected in the world.

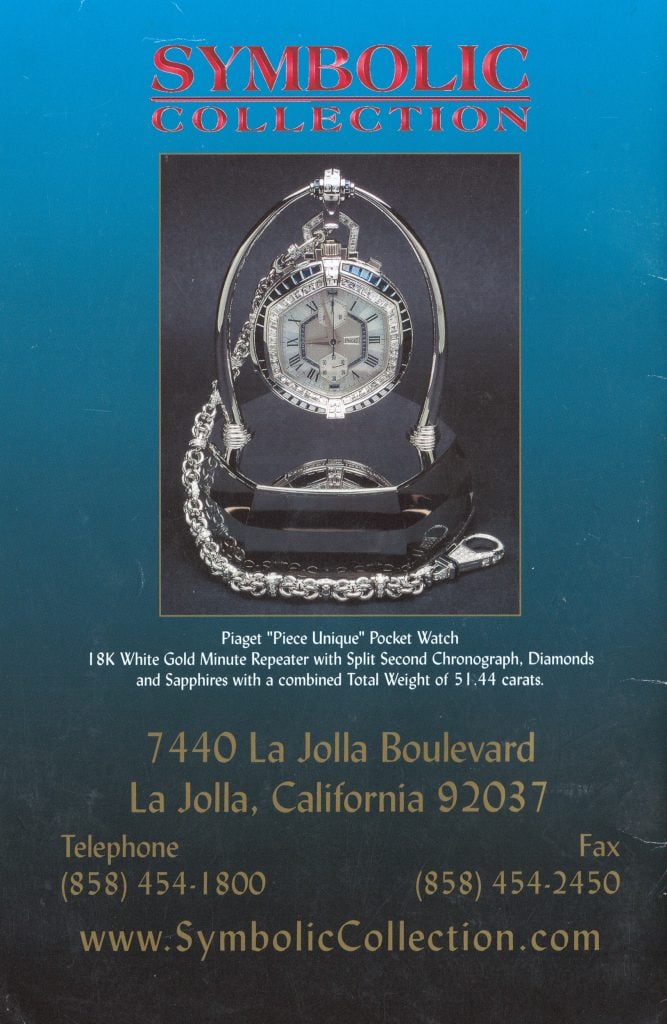

Photo courtesy of Bernie Chase.

KS: Let’s touch on the naughty past.

BC: Well, I was spending a lot of time in London because Symbolic kind of ran a vintage car business with RM Auctions. John Collins had Talacrest—it was a big company in London. He was the first big Ferrari dealer in the world. He had a showroom in London and a showroom in Ascot. Ascot is the main hub in the world for polo and for horse racing. The Queen has a property, Guards. John played a lot of polo, and he had a polo team, and he’d been active at the sport for a long time. He had great respect for putting good teams together, and winning against Brunei, Dubai, Cartier, Hermes, all these big countries and these big corporations that put these teams together.

KS: What about Peter Brant’s team?

BC: I actually can’t say I know much about his team. That was more in the States. It might have been more Palm Beach or Santa Barbara. You had Carrie Packar from Australia, you had the Brunei team, you had the Saudi team—billionaires or these companies had these teams. I was in London then, building my businesses. I had a new company I’d started called Symbolic & Chase and it was on Bond Street. It was a jewelry store and now is a very successful jewelry store. You know what happened at Maastricht.

KS: Did they ever catch the people that broke in?

BC: I don’t know if they caught them all.

KS: They recovered the jewelry?

BC: I think some, not all, but again, I’m not that company, I’m not involved with it today. So John said, “I got a really good idea for you. You want to build your brands in London, I got a way for you to build your brands.” At the time, Prince Charles would take money for his foundations and play on your polo team. So John Collins, we were doing hundreds of millions of dollars for the car trades. Every year, Talacrest and Symbolic.

KS: When was this when you had the polo team?

BC: Ten years ago. My brother, Mark, would do most of the car trading. I was kind of wandering into wanting to do jewelry, wanting to do paintings, wanting to try other things. And so John said, “I can set it up for you, for Prince Charles to play on your team in certain games at Guards. He can be the captain of your team. It’ll get picked up by Polo Quarterly, it will get picked up by everybody. You can start branding your companies off that.” It was a great business plan. I agreed to it.

Photo courtesy of Bernie Chase.

KS: You had to give money to his charity?

BC: I gave money to charities, yes. What worked out well for me is that Polo Quarterly was a really super high-end magazine at the time. I got the opportunity to sit in the Queen’s box at Guards. The Queen would participate—the Queen walking out on the field, me and the Queen giving trophies away, with the Duke, all the time sitting next to him in the box. Her assistant sometimes would come to me and say, “The Queen would like you to escort her out on the field and give away the Queen’s Cup.” A few times I escorted her out on the field and sometimes I went out with the Duke.

One time Symbolic sponsored a big event that Symbolic Motorcar Company played in against Hermès. Harry played on that event—for whom Patrick Hermès is the owner—played against Symbolic. That day we won, Prince Charles made the last goal with 60 seconds to go. It was with Harry; Prince Charles, his mom, and dad was kind of like, “Who is this guy from California in all these pictures? Who is he?”

I used to have conversations with the Queen, and talk about things, mainly charities. We talked about Scripps, which was really interesting to her. She was interested in talking; she was a nice person. She was interesting to have a conversation with. She would talk with me about the California lifestyle and different things. There’s nothing uncomfortable about those conversations. There was nothing uncomfortable about being around her or any of them. I mean, she was a lot more friendly than anybody else in the family. She was the most generous with her time and conversation, more than anybody else.

KS: And what about the Prince Jefri business?

BC: Prince Jefri had a polo team—him and the Sultan had a team. And Jeremy Mains, he was—what are they called?—special forces in the English army. Somehow, early in life, he got involved with Brunei. He took care of the polo team and he took care of everything for Prince Jefri. It was pre-my polo time with Prince Charles, in the ‘90s.

Prince Jefri was kind of a Playboy—the lifestyle, the polo, and he was buying all these great assets, buying big boats, and traveling around the world. Tits I and Tits II were his boats. He was spending money like it was water. He was just buying anything that he liked and all the money was from the Brunei Investment Trust, which he managed. He ran the Brunei Investment Trust, so in theory, I guess it was the country’s money. He invested it, bought all these assets.

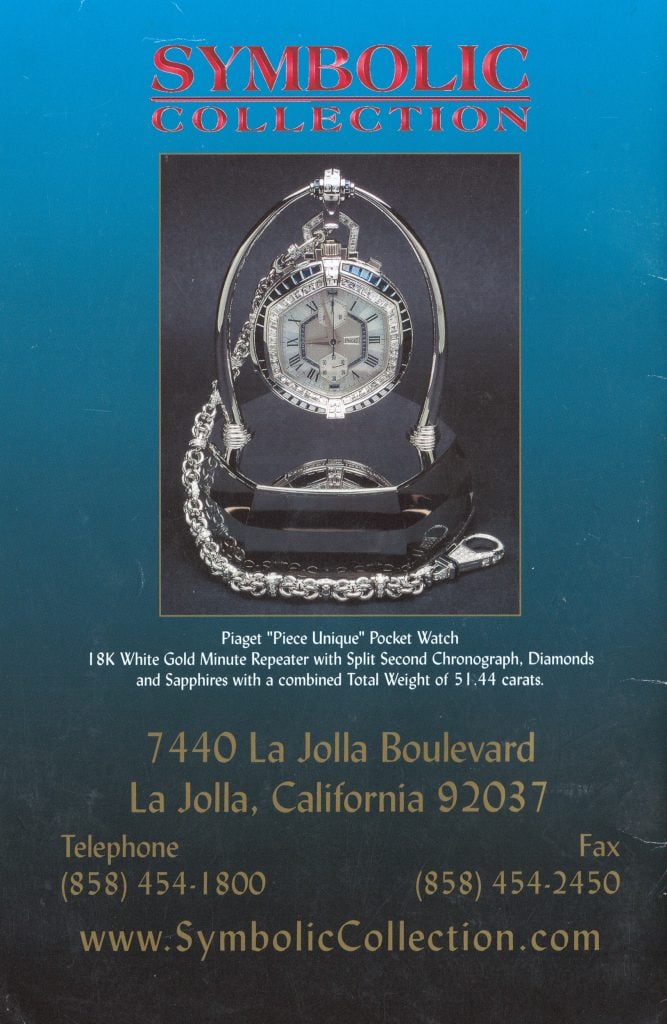

Then the reckoning day came and they needed to be sold. I was selling some stuff to Jeremy that was going into Brunei. Where it really paid off for me was at the end of the ‘90s. Jeremy came to me and said, “Look, we want to liquidate a ton of stuff. We want to liquidate all these crazy expensive watches, crazy expensive diamonds. There’s going to be a deal with all the cars. We’ve known you a long time, you have your hands in a lot.” I was involved in a watch auction company, I was involved in a car auction company that was involved in retail stores. So I said yes, and got involved.

They overpaid for a lot of things. One deal was the Caliber 89s Prince Jefri bought for $40 million. They’re called Caliber 89s, there’s four of them, made by Patek Philippe—he bought all four. One day I showed up at Jeremy Mains and those watches were there. I don’t know what they’re worth now, but they’re worth a lot more than $40 million. So I said, “Look, I can’t afford to buy them, but what I’ll do is I’ll give you a guarantee that I’ll pay you in a set period of time.” It was a package deal that I guaranteed I would pay them $12 million for the four watches that he paid $40 million for. I think one went to the Patek museum, two went to Osvaldo Patrizzi, and one went to the biggest Ferrari collector in Japan, the Matsuda collection.

Then there was lots of other deals like that, real expensive stuff. I mean, Rolls Royce and Bentley were in those days selling 60 percent of all the products they built for the world, just to Brunei. I was mainly moving everything in Switzerland; I was based in Geneva and selling most everything through Antiquorum or through the connections of that auction house. I was auctioning some and private sale-ing some, and it was a great thing. It ran for years and years. Then one of the assets they bought were Aspreys, and they bought Garrards, and then Asprey was sold to Lawrence Stroll and Silas Chou. They did Tommy Hilfiger brand, they did Michael Kors brand, real successful guys. Right now, I think, they’re running the Formula One team for Aston Martin.

Photo courtesy of Bernie Chase.

KS: What did Lawrence Stroll make his money from?

BC: Well, Lawrence’s role started off in Canada. To the best of my knowledge, he was a distributor in Canada for the high end of Ralph Lauren. My understanding is that he became friends with Silas Chau. They took on this Tommy Hilfiger brand, then they sold it. Then they bought Michael Kors and did the same. When Aspreys was sold, they bought it. They only kept it for a while, and they sold it again, and somehow my friend Ron Burkle ended up with Garrards—I’m not sure all the ins and outs how he ended up with it.

Assets were starting to get sold, and I guess in Brunei, there’s little quarrel between the brothers. The Sultan might have done some kind of investigation of what’s going on. There was a law firm in London hired by Prince Jefri to represent him. I don’t know the name of the law firm, but I met one of the lawyers named Joe Hage. He was representing Jefri. I met with him a couple of times and he just wanted to know what I was doing with the assets that I was consigned. My business was perfect: every document was perfect, every sale, most went through auction companies, really good books and records. I had contracts to sell everything that I owned. Then I finished my contract, and soon after that, Joe Hage and Ron Burkle asked me to introduce them to each other.

I set up a meeting to introduce them to each other and they became friends, and then I’ve kind of just watched Joe’s career grow. He wasn’t really in the art world then, but now he’s really taken a grip on the art world. I remember he got involved with Richter around 2000. He would show up at my brother’s showroom in La Jolla, and it was Rolls Royce, Bentley, Lamborghini, Aston Martin, Bugatti, Ferrari, all these brands. At that point, he and Ron had become really good friends.

That was also the end for me; there was nothing more for me to sell. I think Brunei Investment Trust got everything back. I think Prince Jefri had to go under arrest in Brunei for a little while, and he and his brother figured it out. There was Prince Hakeem who lived that lifestyle like Prince Jefri and Prince Bolkiah—they all lived this crazy lifestyle—but at the end of the day, they turned out to be the smartest people in the picture, because Brunei kept all the properties. They kept all the colored diamonds, which they had also been buying. I saw a carpet they had specially made, gold with colored stones, emeralds, sapphires, rubies, on this carpet that hung on the wall. I brokered it to two diamond dealers in Geneva and I think it was, like, $7 million at the time. One stone I remember brokering for $4 million and I recently saw it trade for $35 million because I followed the diamond. Those guys in Brunei ended up with some of the great property Bel Air: they still own the Beverly Hills Hotel, they own the Dorchester Group, the Plaza Athenee. On and on.

KS: When did you get your humble beginnings in business?

BC: My humble beginnings? I had a rough upbringing. I had a problem with self-medicating myself for most of my life. Starting from an age of, like, 10, 11 years old, I was already self-medicating myself. Basically, I became a drug user at a young age. I went to rehab, like, 25 years ago, and they diagnosed me as bipolar. They said, “Even though you are a drug addict, and you’ve been a drug addict, or an alcoholic, you’ve been self-medicating yourself. There was an underlying chemical imbalance and you’re trying to kill the pain.” When you’re bipolar, you go super highs—that’s kind of all of these businesses—and then you go to super lows, when you figure out the mistakes you made.

KS: God knows I’ve got a boatload of mistakes.

BC: More mistakes than successes. At a young age, I was able to get a really good job. I told you I was building cars and this and that and bikes. You don’t make a lot of money doing that. I moved to San Diego, I lived down there, and I got a job at a place called Sunlight Electric. It was an electrical warehouse. My job was unloading and loading trucks with pipe and wire. It was a good paying job. I was getting $2.50; maybe I made it to three bucks, who knows? About 50 percent of the transactions we did were pipe and supply tow trucks from Mexico. I became friends with a lot of these people in the industry; the only friends I had were people that were contractors. I didn’t have any friends there. I had moved to San Diego for the job, so that’s where you really get your friends. One thing led to another and I ended up in Mexico, and I ended up doing some things I shouldn’t have done. I did go to jail for being involved in the marijuana business.

KS: Didn’t you tell me you also taught yourself how to fly a plane?

BC: Yes, well, I didn’t teach myself. A veteran pilot, who had a lot of military hours as a pilot, and then went into the business of smuggling marijuana back and forth, he taught me how to fly. I had enough hours in the air to fly. I had enough ground school education to understand, in theory, most things, but I did not have an actual license to fly.

KS: When you were doing this other business, you were actually flying the plane?

BC: Let’s just say I had flown planes.

KS: Well, you didn’t speak to the Queen about this chapter, did you? How’d you get caught?

BC: I was done doing what I was doing. I was done with the business. I was living in Encinitas, and a guy that I had been in business with a long time got in trouble. See, he ran it and he became a government informant. They had made some kind of deal with him, that they would like to get some information. They would like to have him come into my house, and wear a tape recorder and set me up, all the points to make a case against me, and to get information about a few other people. I thought I was in retirement from it at the moment; I was trying to do real estate deals.

KS: How old were you? You were young.

BC: I was. I was 21. I was doing real estate, and I was trading stones, I was trading rugs. I was just wheeling and dealing. I thought I turned into the treasure hunter that I wanted to be. I was buying a lot of gold in Thailand. You’d have chains, so it was really jewelry, but you’re buying it for the weight. I would bring the gold back to America and sell it as jewelry. I was trading in all kinds of things. The guy came to my house and it was a good friend of mine, and we had done a lot of things in Mexico together. He had moved on to trading in, I think, South America, and had gotten in a lot of trouble. He came into my house wearing a tape recorder and we talked for four hours. We were drinking and partying a little bit, talking. Somehow he kept getting me on the conversation of: life. “Remember this? Remember that?”

I guess, in the old days, they took the tape recorder, listened, ran down to the courthouse, showed some tapes to a magistrate, and the magistrate gave them a search warrant for the house. That afternoon, the same day, late in the afternoon, I remember the gate to my house was open, which was strange. Usually I wouldn’t keep the gate of my house open. This van comes flying into my property, and slams on the brakes. It slid into the garage and actually crashed into my garage door. The side of the van opened up and there’s all these guys with weapons pointing at me. It’s “Freeze!” I don’t know if they said FBI, DEA.

I was outside on the balcony with my dogs, and my dogs attacked them. I had Dobermans. They shot my dogs and killed them. I ran through the house. One of the shots they took at me would have kept me out of jail for a while, because it showed that they shot to kill me, not to stop me.

The bottom line is, I ran through my house to the other side, went to jump over a fence, and someone smacked me in the head with a butt of a gun. I fell back down. At this point, there’s, like, 30 guys on my property. They took me in the house, and they said, “Look, you’re in a lot of trouble and you can go to jail, all this stuff’s gonna happen with you. But we’re willing to make a deal with you. We want to know about a couple of your friends.”

I was a nervous wreck, but I was smart enough to say I needed a lawyer. This happened on a Thursday afternoon. They made sure I couldn’t get out of jail on Friday; the bail was too high. So they had time to search my home, look for receipts, and try to figure out and unravel my life. They were able to unravel my life. I finally got out of jail the next week, and started a two-year court process.

Then I ended up doing a 90-day study in the jail system. They want to study me. I was so young. I was the youngest kid in federal prison. I was in the Metropolitan Detention Center. I was in an MDC for six months. There were no kids in MDC. I was living on the floor with people that were serving life sentences. One night at dinner, one guy murdered another guy at the dinner table. So I had this 90-day observation for the court, because they wanted to figure out how to sentence me, and then I got a five year sentence.

KS: Were the charges for weed? Tax evasion?

BC: I did what was called “Stipulated Facts.” I just agreed to some charges; I didn’t go through trial. It’s not a plea deal. It’s a little bit different than a plea deal. Then after I got a five-year sentence, they really wanted some information about some friends of mine, so they were going to put me in front of the grand jury. That’s when one night, a guy named Scooter, part of the Aryan Brotherhood, killed someone else in the Aryan Brotherhood. I was 21-years-old, sitting at the table. I was witness to this murder.

As soon as my judge found out about that, he got really upset. I never had to go in front of the grand jury. The judge said to start serving my five-year sentence. I ended up going to Lompoc, then I ended up in Terminal Island, all these different places. I got a rule 35 along the way, which is when the judge follows your case—this is the 90-day observation I mentioned. Then they talked to the warden, and my sentence went to three-and-a-half years. I came out and went on this thing called “Special Parole” for 10 years. It meant if I violated it, I served a 10-year sentence. The funny part of this whole story is, the person that they pushed me the whole time to testify about, and give a story, when I came out of prison, that person gave me my first job.

KS: Because you never ratted on him?

BC: He went to jail for nine months for something else. I had a lawyer, Joe Milchin—I’m happy to say his name. He was pressuring me, “Bernie, give up this information.” The guy’s name is Pete Harvey—it’s okay to put it on the record—they wanted Pete Harvey. I said, “Look, I’m just doing my time.” This lawyer was pressuring and pressuring me: “I’m trying to be your lawyer. I’m trying to do the best job for you. Just give up a little information. You’re gonna get pulled in front of the grand jury.”

Finally, I fired Joe Milchin. I lost, like, 20 grand. I hired another lawyer that I would never trade: he wouldn’t take a client that’s a snitch, just wouldn’t take that kind of client. I was never gonna get pressured again. The judge took over my case and put me on the road to serve my time, and I served less than three years, had probation for 10 years, and had to go into a halfway house for, I think, it was six months when I was released. But I got a great job, I was clean. Harvey gave me a great job, and my probation officer agreed to the job. It lasted three years, and I did really well.

It was with this person who owned a lot of pawn shops and jewelry stores, and knew a bunch of them in Houston. It was right at the time I got out of jail, 1984 or 1985 maybe, when Houston had a complete oil bust. Everyone was selling everything and I knew a lot about a lot of different things. I knew about watches, I knew about diamonds, I knew about colored stones, I knew about cars, I knew about treasures. Like I said, I wanted to be a treasure hunter.

So this friend of mine said, “I’m going to turn you on to a really cool business that I’ve done. I’ll get you financing. We’ll give you the financing as long as you need financing, and while we give you financing, we get 50 percent profit. And we’ll give you all the connections, they’re yours.” They took me to Houston and introduced me to about 30 different people that were in watches, jewelry, and the car business. Then they introduced me to a bunch of people in the L.A. Jewelry District that bought watches, jewelry, and stones.

Basically what I did for a little less than three years, every week, for the whole period is this: on Saturday night, I would take the last flight to Houston. I would arrive Sunday morning, early, and I knew where to get the Sunday Times—the Houston paper—at five in the morning. I would get the newspaper and I would mark up the classified ads. I’d mark up all the watches, all the jewelry, and all the cars that were in the classifieds for that Sunday. In the morning, I would start calling everybody up, making appointments, going in and seeing people, making bids on stuff, and maybe at the end of the first Sunday, I only got one thing.

Then during the week, I would just go to pawn shops, I would go to jewelry stores, I would go to car dealerships, I would go to car auctions. I had enough money to buy whatever I wanted, but I was really conservative. All week long, I would buy watches and jewelry. Then I would buy cars, and all the cars would go on outside carriers back to California. That would take a week or two. I worked Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, buying, and then some of the Classified Ad People would call me on a Tuesday. Okay, we’ll take your bid. So maybe I’d get a couple things from the classifieds.

It was a domino effect later. I was getting stuff from a month earlier. So every Friday night, religiously, I’d fly back to L.A. I’d stay downtown near the Jewelry Mart in a hotel. I’d go to the Jewelry Mart Saturday, and I would sell about everything I bought from the week before. I took 100 percent of the bids. I would see 50 people during the day—I was a hustler. I’d be liquid and I’d fly back that night. The next morning, get the newspaper, start again. I had a great business, and I supplied the L.A. Jewelry Mart with a lot of merchandise.

Jail was probably the best thing happening in my life, because it set me on the straight and narrow, straightened me out. I found out a little bit more about who I was, instead of just a confused kid. It taught me discipline, focus, to take care of myself, to keep to myself, to study. For me, it was a blessing in disguise. It gave me my work ethic, believe it or not. The first industry that my brother and I built was cars, and then later we ended up owning auction companies. Now we’re at the bottom of the circle, living a simple life here in New York.

KS: When did you open your first art gallery?

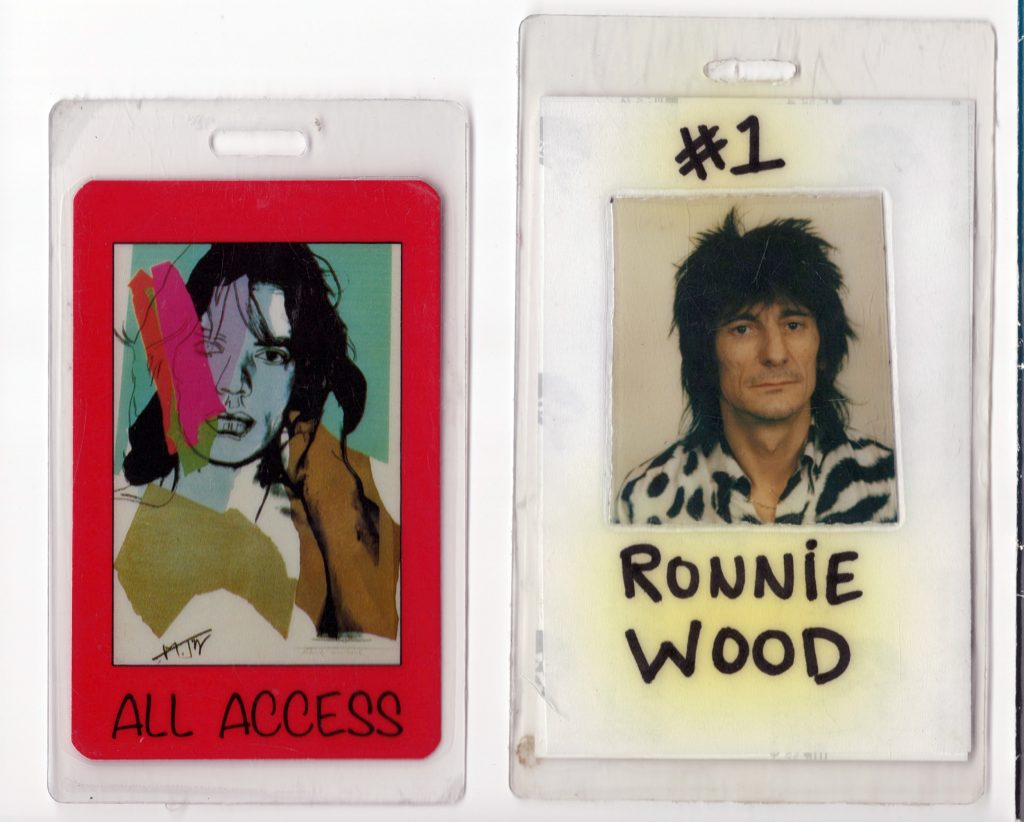

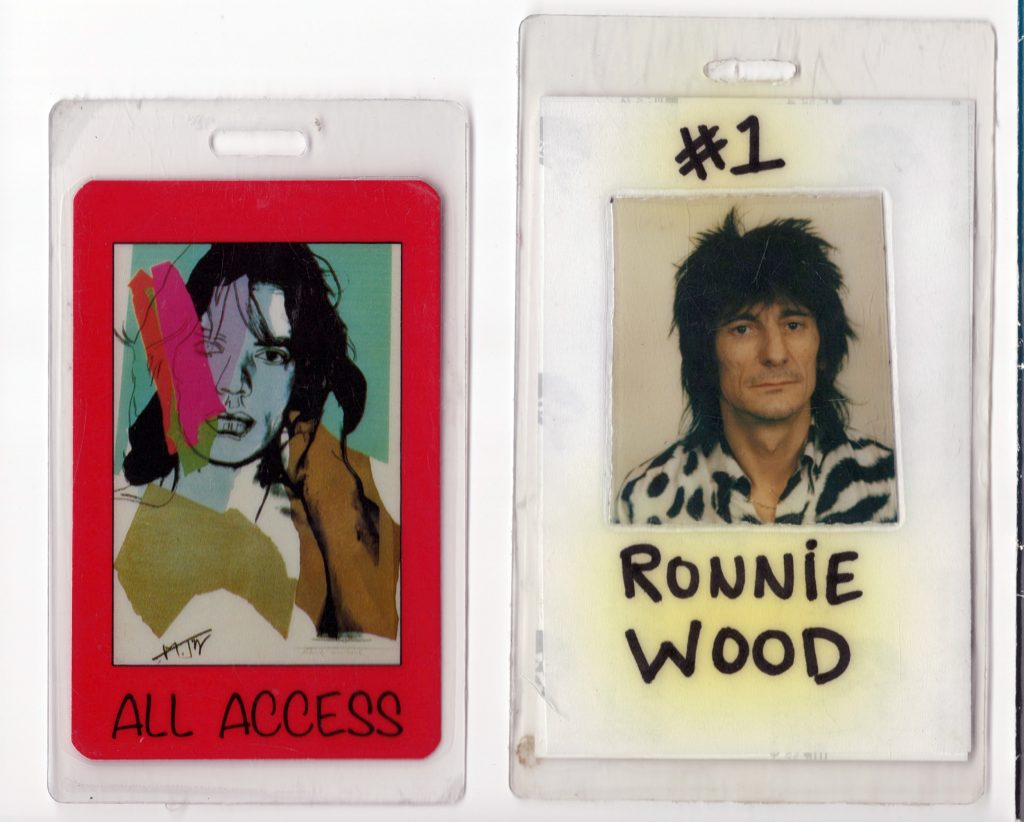

BC: The first art gallery was—well, I didn’t open it up. It was owned by Ronnie Woods, by the Woods family. That was my first art gallery as a partner.

KS: How did you meet them?

BC: I was hanging out with Brunei, and Brunei owned the Dorchester, and Prince Jefri and Prince Hakeem stayed there with their friends. So I had a free place to stay all the time because I was working for them. Ronnie would come to stay at Dorchester a lot with them and he was his own celebrity. I met his kids and I became friends with his kids. One of them, Tyrone, was running Scream Gallery at the time.

Photo courtesy of Bernie Chase.

KS: Tyrone works now for Maddox Gallery now.

BC: Right. I became friends first with his kid Jamie, then Tyrone, and I started working with Scream, then became a partner. I became good friends with Ronnie too and he had me manage his art career. We did pop-up shows around the world, and I produced concerts. I traveled with the Rolling Stones for multiple years. It was all business for me. There was always one person who introduced me to another person and to another person to sell something.

KS: When did you open the space here?

BC: The first space we opened was in Chelsea, and it would have been nine years ago. We had three spaces in Chelsea, and then one five-year lease ran out, so we had two spaces in Chelsea. Then a company from Texas bought our leases and made a deal, and took the spaces in the middle of the pandemic.

We were hanging around Soho a lot—the town was completely melting down, everything was going underground. There’s one art gallery I liked a lot and it disappeared overnight. We met with the landlord and made a deal, and we opened Chase Contemporary in SoHo. It’s between Prince and Spring. Now it’s been about a year and a half. We’re doing artist studios, and we’re doing fashion, and we’re trying to do something more related to the period of the ’80s in Chelsea. Where studio artists come to work in the studio and they do a show. We’re having a good run so far. One day at a time.