Georgia O’Keeffe had a show every year in New York. Her husband, the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, helped her achieve this luxury, which no other female American artist enjoyed in the 1920s and ’30s, including O’Keeffe’s talented younger sister, Ida (although Stieglitz was also keen on his sister-in-law and her art).

“There was a bit of sibling rivalry,” says Sue Canterbury, associate curator of American art at the Dallas Museum of Art, who is organizing an exhibition that aims to give Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe (1889–1961) the credit she deserves as a significant artist in her own right. In Georiga’s opinion, “There was only room for one painter in the family,” Canterbury says.

Alfred Stieglitz, Ida O’Keeffe (1924)

American art history could have been very different if Stieglitz had promoted both Georgia and Ida’s work. But relations between the sisters became strained, thanks in part to Stieglitz’s roving eye. Canterbury says that there are some “racy letters” written by Stieglitz to Ida in the late 1920s. She also posed for him.

On the reverse of his photographs, which will feature in the Dallas show, are inscriptions that indicate that he would have liked a relationship of a more “intimate” nature. Ida was “outgoing, gregarious and fun—the different side of the coin to Georgia,” Canterbury tells artnet News. (There is no evidence that Ida took advantage of her brother-in-law’s advances.)

Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe, Creation (date unknown).

For the past four years, Canterbury has been hunting down Ida’s paintings, drawings, and prints for the exhibition “Ida O’Keeffe: Escaping Georgia’s Shadow.” The show, which is due to open in the fall, will include more than 40 never-before-seen and rarely-exhibited works by Georgia’s younger sister, including six of the artist’s seven lighthouse paintings.

Ida’s bold and increasingly abstract compositions featuring “dynamic symmetry” are quite unlike her older sister’s more celebrated paintings of buildings and landscapes. Canterbury hopes that the missing lighthouse in the series will emerge. “I know it’s out there,” she says, “but the trail has gone cold.”

Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe, Variation on a Lighthouse Theme VI (1931–32).

Many of Ida O’Keeffe’s works are in private collections, which has made organizing the exhibition more of a challenge. The artist’s habit of tweaking titles as well as dates to works painted earlier in her career has increased the difficulties. One of her most accomplished works, Star Gazing in Texas (1938), which features a young woman bathed in moonlight, is now in the Dallas Museum’s collection. Acquired late last year, Ida O’Keeffe created the work, which includes a frame painted with stars, while teaching in San Antonio.

Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe, Star Gazing in Texas (1938)

A graduate of Columbia University in 1932, Ida O’Keeffe, was a late starter as an artist and was never able to support herself by her art. She moved around a lot during the Great Depression for the short-term teaching posts that provided her main income. Practical and ingenious, she used an electric iron as a printing press to make her monotypes. She even found time to research and publish a book on Native Americans in 1934.

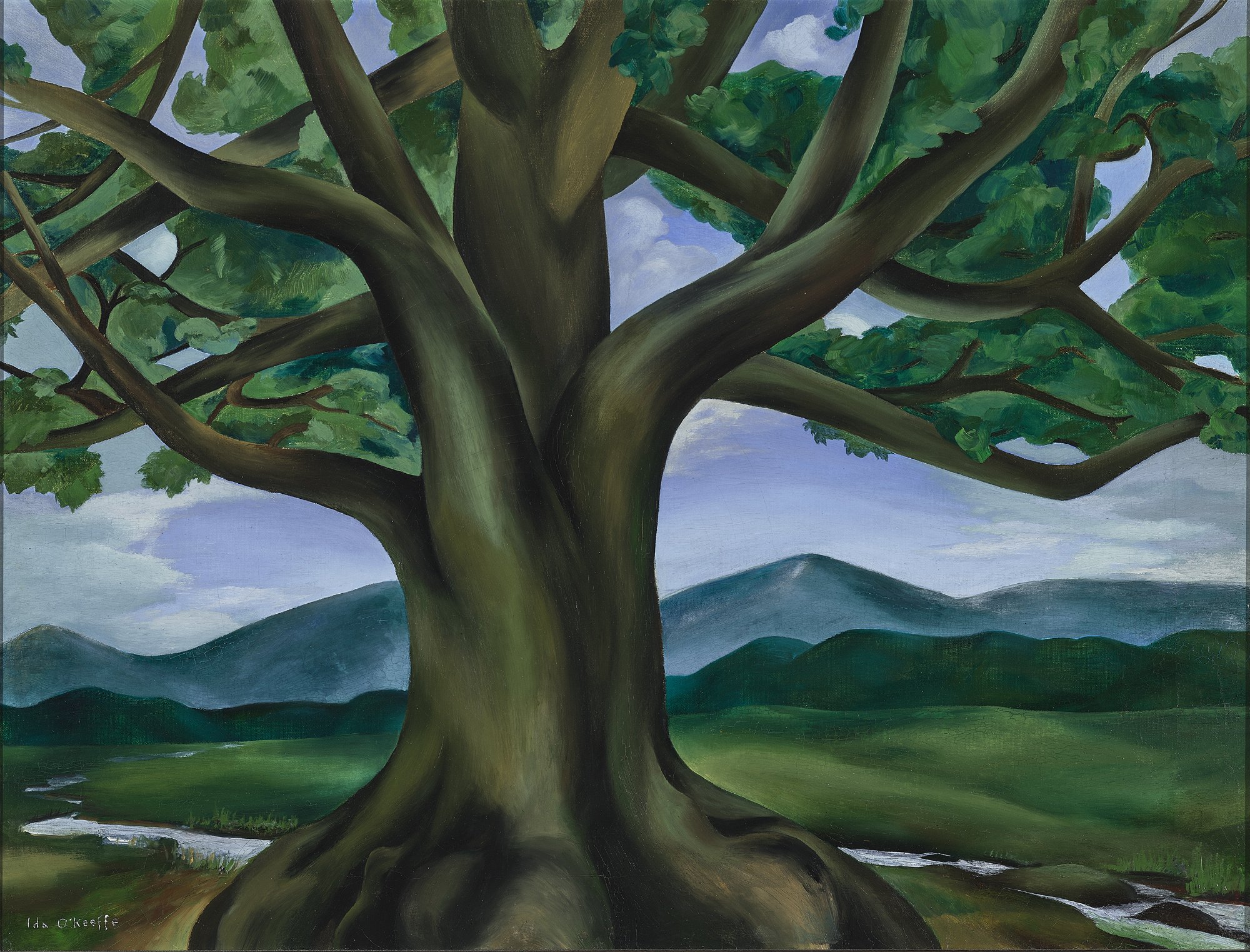

Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe, The Royal Oak of Tennessee (1932).

Georgia O’Keeffe famously stayed put in New Mexico and focused on her paintings. When she did travel, such as to Hawaii in 1939, it was at the expense of the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (later called Dole). There she painted what she liked, which did not include many pineapples, as the show “Visions of Hawaii,” now on at the New York Botanical Garden confirms (until October 23). There was only one exhibition that included work by the two O’Keeffes in their lifetimes, and it wasn’t organized by Stieglitz. For Georgia, “It was OK for Ida to paint but not exhibit,” says Canterbury.

“Ida O’Keeffe: Escaping Georgia’s Shadow” is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art, 1717 North Harwood Street, Dallas, Texas, November 18–February 24, 2019.