Art World

Looters Are Taking Advantage of the Worldwide Lockdown to Rob Cultural Heritage Sites—and Selling Their Stolen Wares on Facebook

Historic sites in the Middle East and North Africa are more vulnerable than ever.

Historic sites in the Middle East and North Africa are more vulnerable than ever.

Sarah Cascone

As archaeological sites become increasingly vulnerable to looting amid global lockdowns, Facebook has emerged as an increasingly popular hub of the illicit trade.

The Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research Project, which monitors efforts to traffic stolen artifacts in the digital underworld, has seen a recent surge of activity on the social-media platform, particularly concerning looted objects from the Middle East and North Africa.

Last week, a historic mosque in Morocco was looted and the images were shared over illicit groups on the social-media platform, the Art Newspaper reported. Such photos help the seller demonstrate the authenticity of their wares, and can yield tips from other group members about how to proceed with excavations.

These Facebook groups “are often private and designed specifically for the purpose of trafficking or engaging in illegal digging,” said the project’s co-director, Katie Paul, in an email to Artnet News.

“The individuals operating in these groups are not end-market buyers and are well aware of the fact that what is traded in these groups is illegal,” Paul said. “In many cases where people post looting photos they will blur or block out their face with an emoji so as to not be identified in association with the crime.”

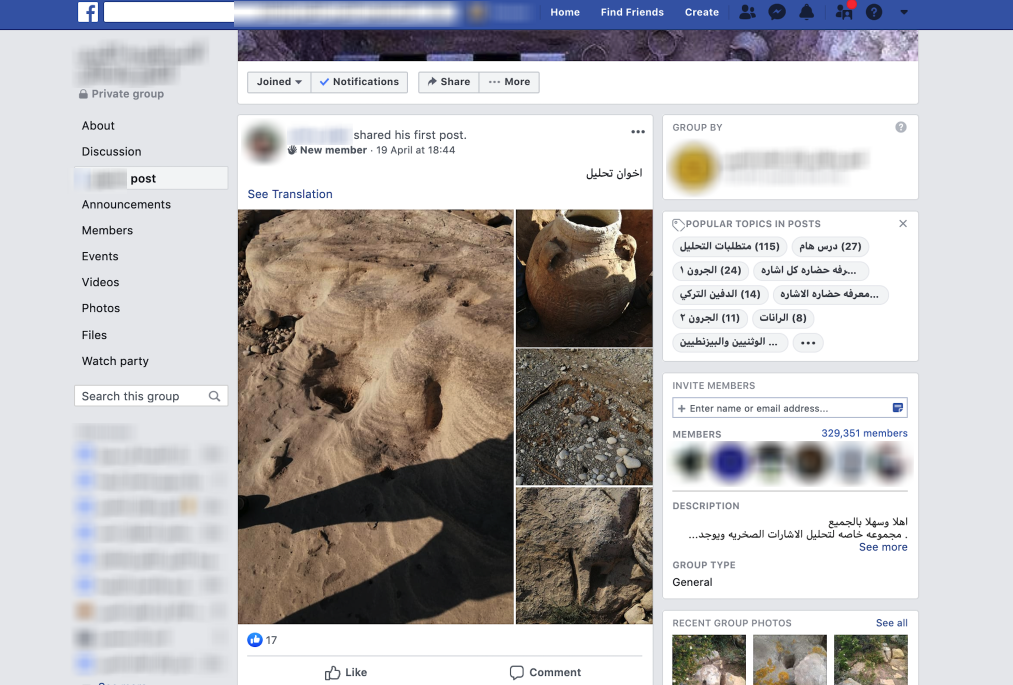

Active looting and pottery in situ posted by a user listed in Khanaqin, Iraq. Screenshot courtesy of the ATHAR Project.

Some people offering stolen artifacts may have turned to looting as other forms of income dried up amid the lockdown. Other factors contributing to the rise in illegal excavations are the lengthening of daylight hours and increasingly warm weather, which makes digs easier to carry out.

“The looting of archaeological sites and museums thrives during times of crisis—the Arab Spring spawned a new wave of looting across the Middle East, the Greek museum in Olympia was looted as the country faced widespread anti-austerity protests, the Kiev History Museum was looted during a period where police and protestors clashed,” said Paul. “The common thread between all of these crises is that authorities were occupied with other issues, and that’s what we’re facing today.”

The project is monitoring trade activity in the Middle East and Africa, in places where “these transactions are absolutely illicit,” Paul said. “The countries represented by these looters are places where no legal trade exists.”

Much illegal excavation is tied to criminal organizations or terrorist groups in conflict areas. And authorities often have a hard time shutting down illegal trading. “Preventing the sale of loot is difficult because the transactions occur quickly since they do not involve due diligence or purchase agreements,” art and cultural heritage lawyer Leila Amineddoleh told Artnet News in an email. “By the time law enforcement learns of the exchanges, the objects have likely disappeared deeper on the black market.”

User in Cairo advertising his services for scuba-diving to loot in a tomb that is filled with groundwater on February 21. Screenshot courtesy of the ATHAR Project.

In response to a report from the antiquities research project that identified groups trading artifacts on Facebook last year, the platform tried cracking down on the activity. But while the company removed 49 groups linked with trafficking, the researchers contended that there were still 90 other groups where the blackmarket trade continued.

“Facebook needs to include a ban on this activity in its community standards and commerce policies and actually enforce that ban,” said Paul. “But it also needs to ensure that it preserves and archives this data. Not only do these photos and videos serve as evidence of war crimes in the cases of Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya, but they also serve as a critical record of an object’s existence, particularly in the cases of artifacts offered while in situ.”

For at-risk archaeology sites, International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas announced this week that it would allocate emergency funding to affected cultural heritage sites in conflict regions. Other possible resources include the World Monuments Fund, which operates a Crisis Response Fund that helps cultural heritage sites that have been damaged during disasters.