Art & Exhibitions

What a French Jewelry Exhibition in Beijing Reveals About China’s Imperial Vision for Its Future

In the Forbidden City, a display of treasures from France's Maison Chaumet reflects a resurgent nation's far-reaching ambitions.

In the Forbidden City, a display of treasures from France's Maison Chaumet reflects a resurgent nation's far-reaching ambitions.

Nazanin Lankarani

On a breezy Monday afternoon, a crowd of dignitaries gathered at the foot of the steps leading up to the tower of Wumen Gate, one of the majestic galleries of Beijing’s Palace Museum, located at the heart of the Forbidden City. They were there for the official opening of an exhibition titled “Imperial Splendors: the Art of Jewelry Since the 18th Century.”

Given the title and venue, one could naturally assume that the show is about Chinese imperial jewelry. After all, as China’s largest cultural institution, the Palace Museum boasts a collection of ancient artworks totaling over one million pieces that include jewelry, jades, clocks, paintings, porcelain, bronzes, and other treasures from several dynasties of Chinese imperial families.

Left: Hair pin with dragon motifs, Qing Dynasty. Right: Hair pin known as “The Child With a Vase,” Qing Dynasty. Photos courtesy the Palace Museum, Beijing.

Actually, the exhibition—which opened to the public on April 11 and runs through July 2—has been mounted by the French jeweler Maison Chaumet. Through some 300 pieces of jewelry, art, and craft, it explores the history of the preeminent luxury house, the evolution of its style, and the transmission of its savoir-faire over two centuries—devoting an important chapter to Chinese influences on its art.

The exhibition, as splendid as it is edifying, marks the first time that a Western brand has been allowed to furnish an exhibition in the Forbidden City.

“We chose the Forbidden City, a symbolic and historic site, for a show that is a testimony to the universality of artistic expression and to celebrate the creativity of both French and Chinese artists,” explained Jean-Marc Mansvelt, president of Chaumet.

The pieces are mostly from Chaumet’s own collections, with many—though not all—carrying an imperial provenance, as the show’s title would suggest. Since the French Revolution, Chaumet has catered to European courts, including two French emperors. Other pieces are on loan from private collections and 17 museums, from the Louvre and the Victoria & Albert to smaller collections in France like Compiègne and Fontainebleau. Several pieces come from the Palace Museum’s own holdings.

A view of the Palace Museum, Beijing. The exhibition “Imperial Splendors” is on view April 11–July 2, 2017.

With the Forbidden City closed to the public on Mondays, the opening ceremony had an improbably exclusive feel—a gathering of social elites and other luminaries within a stone’s throw of Tiananmen Square—as guests attended the ribbon-cutting event on the deserted esplanade of the former imperial palace, normally bustling with thousands of visitors.

The symbolism of the day was manifest as Shan Jixiang, president of the Palace Museum, began to speak: he was flanked by Maurice Gourdault-Montagne, the French Ambassador to China; Henri Loyrette, former director of the Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay; and Mansvelt.

Shan underscored the importance of having the show in China as a demonstration of the country’s readiness to step onto the cultural stage as a global player. “The show demonstrates the absorption of an exceptional engagement with Chinese culture,” Shan said through an interpreter. “Having these pieces of jewelry side-by-side allows us to measure China’s impact on European traditions.”

The history that Chaumet deploys across “two centuries of stone and metal”—to borrow Loyrette’s poetic language—is mostly its own, told as an uninterrupted chronology that begins with its earliest known object: a memorial box made in 1789 for the Marquise de Lawoestine that traces the jeweler’s relationship to the court of Marie Antoinette.

That history continues to its most recent creation, the “Vertiges” tiara that was produced this year from an original drawing by Scott Armstrong, an English student of London’s Central Saint Martin’s school who won a design contest to mark the opening of this exhibition.

“We have always been open to all cultural influences,” Mansvelt said, playfully.

Because of its privileged status vis-à-vis the ruling classes, the history of Chaumet necessarily evokes important chapters of the history of France itself.

Left: François Gérard, Emperor Napoléon I(1806). Courtesy Palais Fesch, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Ajaccio. Right: Consular Sword, also known as Napoléon I Coronation Sword (1802). Courtesy Musée national du Château de Fontainebleau.

Napoléon I’s coronation sword, for instance, is on display as a centerpiece of the show, having left France for the very first time on loan from the Château de Fontainebleau. Made in 1802, the sword was commissioned by Napoleon from Marie-Étienne Nitot, the founder of the Maison. Originally set with a 140-carat stone known as the “Regent Diamond,” it accompanied the emperor on the occasion of his coronation at the Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral in 1804.

Suspended in a glass case before a standing portrait of Napoléon by François Gérard—itself on loan from the Palais Fesch, home of the Musée des Beaux Arts of Ajaccio in Corsica—the sword takes on a new majesty, thanks to the inspired vision of Richard Peduzzi, the exhibition’s set designer.

Chinese influence on French aesthetics is traced in the show primarily through objects belonging to the Qing Dynasty—for instance, a chiseled jade pendant is likened to a 1930s piece by Chaumet, depicting a Chinese vessel carved out of jade. A number of objects including fans, ornamental headdresses, baroque pearl hairpins, and even a tea set from the collection of the Palace Museum, draw attention to the similarities between Chinese and French craftsmanship. Sometimes they come so close as to be practically indistinguishable.

“China’s influence on the arts in France is seen in the 18th century in what we call ‘chinoiseries,’” said Loyrette, an expert on the arts of the 19th-century who is credited as a “scientific collaborator” on the show. “Starting with the world fairs in the latter part of the 19th century, France went looking for exotic sources of inspiration. China was one such source.”

Chaumet, Octopus necklace with diamonds, jasper, and rubellite (1970). Collection of Her Royal Highness Princess de Bourbon des Deux Siciles.

For China to host a show of imperial art and craft is itself testimony to the seismic shift that has taken place here since 1966, when the Cultural Revolution got underway. Given China’s current posture toward culture, it is hard to believe that a decade-long campaign in the name of fighting capitalism had ravaged the country only 51 years ago.

Today the opposite is happening. The Palace Museum was established in 1925, a few years after the last Chinese emperor, Puyi, had abdicated after the revolution that ushered in the People’s Republic. According to the China Daily newspaper, it now receives over 15 million visitors annually—and Chinese authorities are looking to attract more.

“The Palace Museum is home to objects collected over 600 years,” Shan said. “We are the fifth largest museum in the world, but we are using only part of our space. We hope to add more space to display more treasures and bring in more visitors.”

Ambitious museum-building is also moving full speed ahead across China as the country carves out a place in the international museum community, actively seeking to reconnect with its ancient history and to tap into the opulence of its imperial past, serving to underscore China’s relevance and potency in the present.

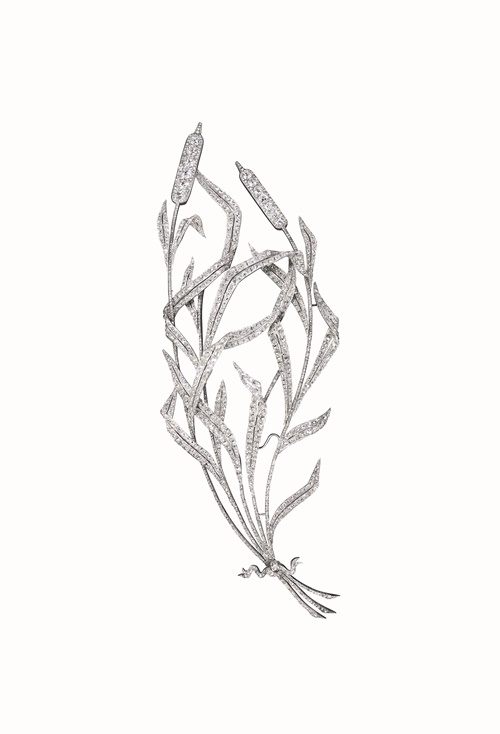

Joseph Chaumet, gold and diamond brooch, (c.1893). Private Collection of Her Royal Highness the Princess of Hanover.

“This show is a symbol of the growing rapprochement between France and China,” Mansvelt said. “We want visitors to leave this show transformed, with a new window on history and shared cultures. Great civilizations build on what they have done before.”

These words certainly apply to Chaumet, for whom the show provides a spotlight on a glorious heritage and a base upon which to build “for the next 200 years,” starting right here in China, a significant growth market for the luxury brand.

“Culturally speaking, things have changed very rapidly here, given the size of the country and its population.” Mansvelt said. “The Forbidden City itself is an emblem of that change, of China rediscovering its own symbols and history.”

While the sense of national identity is intact in the Palace Museum, Chinese cultural history remains as hazy as the Beijing sky. This show is an invitation to Chinese visitors to take an interest not only in French culture but also in the cultural affinities their country shares with France—in order to remember their own history, revive it, and acknowledge where they came from and what they have.