As current circumstances draw comparisons to medieval times, the Getty Museum presents “The Fantasy of the Middle Ages,” an exhibition that pairs illuminated manuscripts dating back to the 1200s with modern relics inspired by the era, from Brothers Grimm to Lord of the Rings.

The show presents nine manuscripts alongside objects on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, UCLA, even the Getty’s own staffers (think: Beanie Babies, Dungeons & Dragons). One prayer book circa 1450, for example, is echoed in Eyvind Earle’s concept art for Disney’s Sleeping Beauty (1959).

The juxtapositions reveal just how much medieval times—and the epic adventures of heroism, romance, and magic we associate with them—have saturated American culture, and the hazy bounds between fact and fantasy that exist in popular (mis)understandings of the Middle Ages.

“This exhibition aims to tell a visual story about how these elements appear in medieval examples, and how they have been changed over time and layered with new cultural and social meaning to result in our modern version of what constituted the Middle Ages,” Getty assistant curator Larisa Grollemond told Artnet News.

Unknown Franco-Flemish, A Dragon (ca. 1270). Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

The idea for the show began with a 2014 social media initiative titled “Getty of Thrones,” which recapped HBO’s Game of Thrones episodes with imagery from the museum’s singular collection of medieval manuscripts. The Getty first began collecting in the category in 1983 to help bridge the “chronological gap between the antiquities and Renaissance paintings that Getty himself had collected,” according to Grollemond.

The social media initiative evolved into Instagram videos “addressing audience questions about links between the ‘real’ Middle Ages and the medieval-inspired world presented in the show,” Grollemond said. Obviously, there weren’t really dragons back then, but even the architecture of medieval-inspired media comes from a self-referential culture resembling Orientalism. “The Fantasy of the Middle Ages” exhibits a 1879 photo called “Stairway of Christ Church,” for instance, that bears striking resemblance to the entrance at Hogwarts. “This was probably not something the filmmakers looked directly at,” Grollemond told the L.A. Times.

“The Fantasy of the Middle Ages” continues that conversation over two galleries and six sections—a story of storytelling, rooted in mesmerizing drawings of painstakingly preserved tempera, ink, and, of course, gold leaf.

“There’s a very complex interweaving of fantasy and history in these contemporary takes on the Middle Ages,” Grollemond said. “The ‘medieval’ world that fantasy stories present has the power to shape our view of the historical Middle Ages as well, and so continues to be hugely relevant for artists, creators, and audiences today.”

Below, see more cultural comparisons from “The Fantasy of the Middle Ages,” on view at the Getty Museum through September 11, 2022.

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Parting of Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere (1875). Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

C. Hertel, Stolzenfels Castle (1878). Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

Loyset Liédet & Pol Fruit, The Battle Between Arnault de Lorraine and His Wife Lydia (1467-72). Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

Master of Guillebert de Mets, Saint George and the Dragon, (ca.1450-55). Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

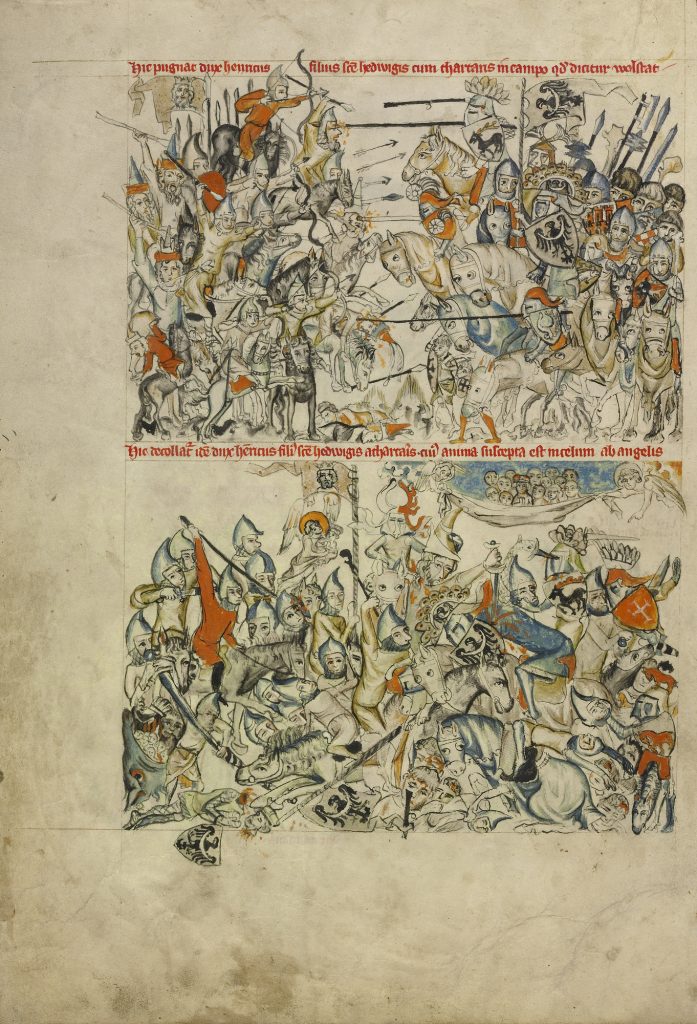

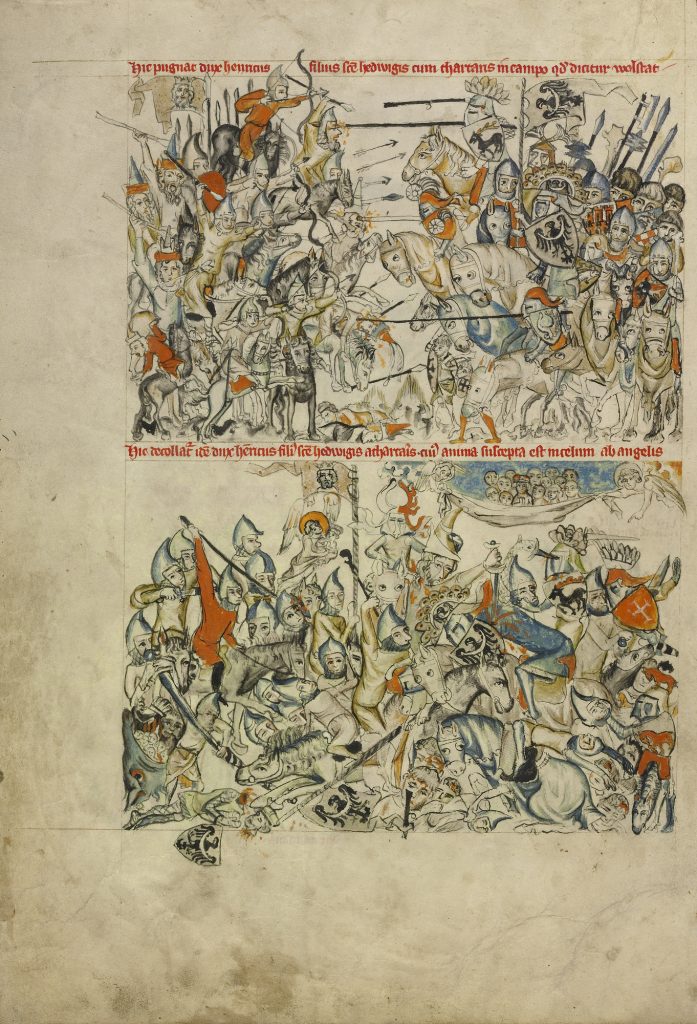

Unknown Silesian, The Battle of Liegnitz and Scenes from the Life of Saint Hedwig (1353). Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

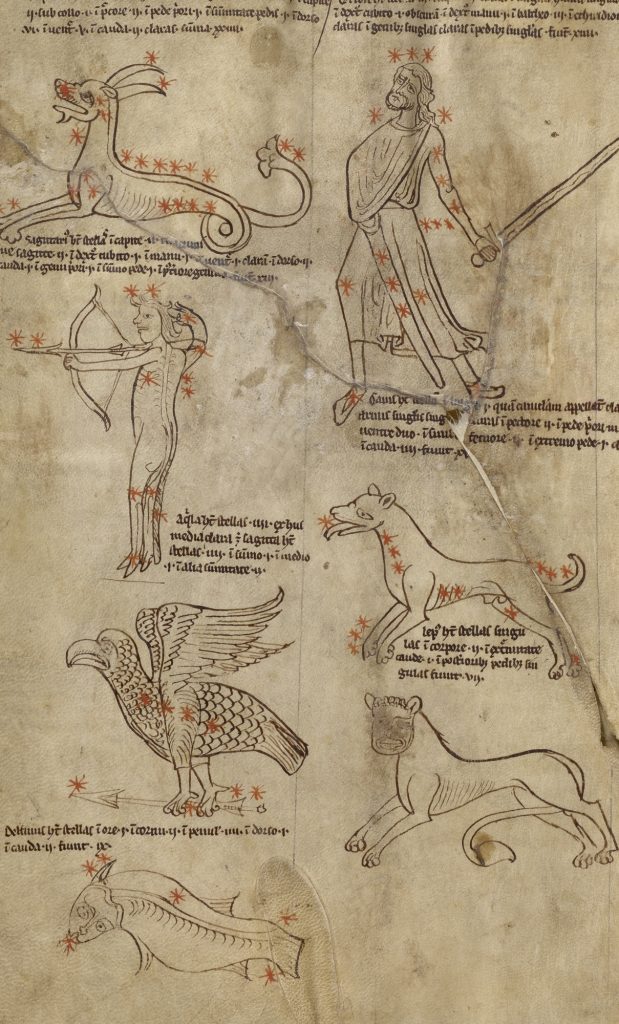

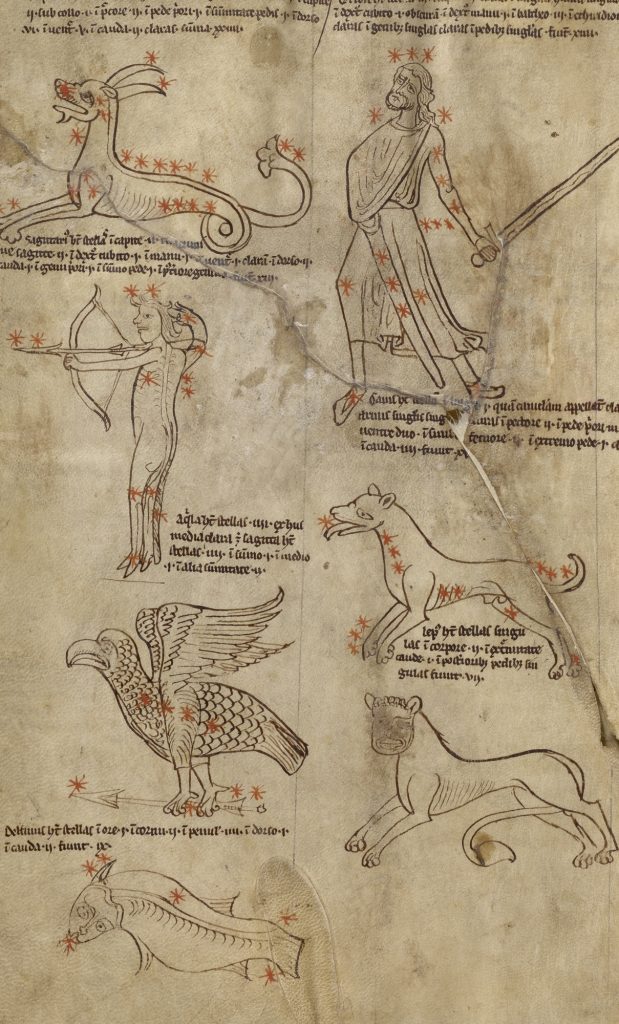

Unknown English, Constellation Diagrams (1200s). Courtesy of the Getty Museum.