Law & Politics

A Bombshell Lawsuit Claims That High-Flying Art Dealer Inigo Philbrick Swindled His Clients by Selling the Same Rudolf Stingel Again and Again

The case includes accusations of a fake auction guarantee and double-dealing.

The case includes accusations of a fake auction guarantee and double-dealing.

Eileen Kinsella

A multimillion-dollar painting by market star Rudolf Stingel is at the heart of an apparently fast-widening scandal involving London- and Miami-based art dealer Inigo Philbrick. The case, which includes accusations of a fake auction guarantee and double-dealing, lifts the curtain on a segment of the market fueled by increasingly byzantine deals involving anonymous corporations, partial ownership, and fast flipping.

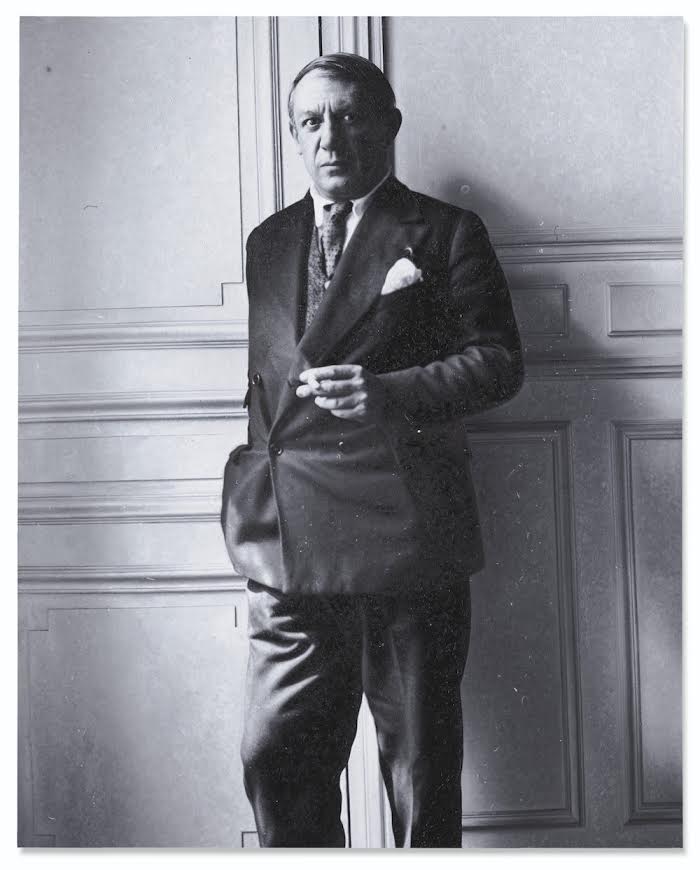

Philbrick, a well-connected dealer who got his start at London’s White Cube gallery, allegedly sold an untitled 2012 Stingel painting—one of the Italian artist’s signature black-and-white photorealist works that depicts Pablo Picasso as a young man—to multiple entities and misrepresented its ownership status to clients, legal documents claim. (To be precise, according to the suit, he sold the same painting one-and-a-half times—selling it in full to one client while offloading a 50 percent share to another—all while representing to a third party that he still owned it.) Neither Philbrick nor his attorney responded to Artnet News’s request for comment.

The lawsuit also alleges that Philbrick forged documents falsely representing negotiations with Christie’s auction house, including that the house had given him a $9 million guarantee for the Stingel painting when it was consigned to auction this year. As it turns out, court documents show, Philbrick was not even the official consignor of the work. Instead, it was sold by an offshore entity to which he sold the work almost two years earlier.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled (2012). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Now, at least three parties are attempting to stake a claim to the painting. On November 1, a plaintiff by the name Guzzini Properties, identified only as “a company that collects art,” filed an action in New York State Supreme Court asking a judge to confirm its title to the Stingel. (Rather than name any individual in the complaint, the action specifies the Stingel painting itself as the defendant property.)

“We are confident that the New York Supreme Court will thoroughly review the facts and will uphold our client’s rights to the artworks,” Guzzini’s attorney Wendy Lindstrom told Artnet News.

Philbrick has the kind of art-market pedigree any aspiring dealer would covet. He started out running secondary-market sales for White Cube gallery and was once described by former Phillips chairman Simon de Pury as “one of the most talented young art dealers.”

Between 2011 and 2013, according to publicly available business records, he worked at Modern Collections, a private, London-based secondary market dealership co-directed by Jay Jopling, White Cube’s founder. Philbrick resigned as a director in 2013, records state, and went on to set up an eponymous shop in London. Last year, he opened another gallery in Miami, which now appears to be closed. (A call to the gallery went unanswered.)

Together, the legal documents filed in the saga paint a picture of a complex, overlapping web of deals. The story begins in 2015, when Philbrick began working with a German finance company called FAP, or Fine Art Partners. Under the terms of their agreement, FAP and Philbrick would acquire works, Philbrick would broker the sales of those works, and they would share the profits.

Among the works they acquired are two stainless steel works by Donald Judd; a piece by Wade Guyton; two Christopher Wool paintings; a work by Yayoi Kusama that is now on view at the ICA Miami; and two Stingel paintings, including the 2012 picture of Picasso. The haul was worth more than $14 million, according to court documents.

Philbrick successfully sold the 2012 Stingel, according to legal filings, in June 2017 to Guzzini Properties. The company paid $6 million for the painting, plus two other works that were not named in the lawsuit.

Philbrick then wrote to a storage facility in Switzerland that had been holding the Stingel and the two other pieces, instructing them to “hold the artworks for the benefit of Guzzini,” to which title had been transferred, court documents state.

Almost two years later, in March 2019, Guzzini consigned the painting to Christie’s, where it appeared in the New York evening sale of postwar and contemporary art this past spring. At the May 15 auction, New York-based Stellan Holm Gallery placed the successful bid of $5.5 million for the Stingel. Including premium, the final price was $6.5 million. (According to Guzzini’s complaint, the buyer has yet to pay in full for the painting and the work is currently being held in storage by Christie’s.)

Part of the problem? Guzzini is not the only entity to whom Philbrick sold the Stingel, the suit states. In January 2016, Philbrick also sold an additional 50 percent share of the painting, for $3.35 million, to a man named Aleksandar Pesko, part of a business entity known as Satfinance Investment.

Judd Grossman, a Manhattan art lawyer representing Pesko and a number of individuals and entities impacted by the alleged scheme, says that “when all is said and done, unfortunately this may turn out to be one of the most significant frauds to rock the art world in recent memory, right up there with Salander-O’Reilly and Knoedler.”

As Guzzini pursues the Stingel in court, FAP has also filed suit against Philbrick in Miami. Earlier this month, FAP’s principals, David Tümpel and Loretta Würtenburger, filed a claim seeking the return of at least eight works (including the aforementioned Stingel) worth a reported $14 million.

The FAP filing contains more than 100 pages of emails, including exchanges between Tümpel, Württenburger, and Philbrick that reflect their increasing frustration with Philbrick’s limited success in selling works and remitting payments. The exhibits reveal that they eventually became suspicious enough about Philbrick’s activity, including what they describe as the possibility of “criminal” behavior, that they cut the dealer out of the conversation and went to Christie’s directly, asking them not to alert Philbrick for fear of losing even more artwork and money.

As a result of their communications with Christie’s, FAP’s principles learned that Philbrick was not even the official consignor of the Stingel, but that it was instead being sold by an “offshore entity”: Gazzini. Even more scandalous, FAP claims that Philbrick had lied when he told them that Christie’s extended a $9 million guarantee for the work. (In addition to the fact that no symbol was placed next to the lot to designate a guarantee in the catalogue, it wouldn’t make sense for a painting with a $9 million guarantee, or minimum price, to sell for considerably less at $5.5 million.)

In an email exchange included in legal filings, Christie’s general counsel suggests that FAP was provided a falsified agreement with different terms, including the level of the guarantee, than those the auction house agreed to.

“Since Christie’s initially discovered the fraudulent use of our brand and falsification of our paperwork, the consignor of the painting has commenced litigation to validate their ownership of the painting,” Christie’s told Artnet News in a statement. “While Christie’s is not a party to any filings, we will continue to hold the artwork while ownership of the painting is determined through the judicial system or otherwise.”

Neither Tümpel nor the Miami-based attorneys for FAP responded to Artnet News’s request for comment. An attorney for Stellan Holm Gallery could also not be reached for comment.