Law & Politics

As Fallout From the Inigo Philbrick Scandal Rages on, Investors Go to Court to Claim Ownership of a $12 Million Twice-Sold Basquiat Painting

Investors and collectors are trying to untangle the mess left by the indicted dealer.

Investors and collectors are trying to untangle the mess left by the indicted dealer.

Eileen Kinsella

A legal fight over who owns an eight-figure Jean-Michel Basquiat painting, Humidity (1982), is heating up as a billionaire collector and a high-profile lender battle it out in federal court. The case is yet another part of the stunning fallout of disgraced dealer Inigo Philbrick’s massive alleged fraud, which has left his former clients scrambling to recover money and assets.

Satfinance, an offshore company controlled by collector Sasha Pesko, filed a motion late last month that delves deeper into the complicated deal and reflects the extent of Philbrick’s convoluted dealings. Pesko invested $12.2 million in the Basquiat painting in 2016 at the behest of Philbrick, believing it gave him ownership of the title and the right to share in proceeds of a profitable resale at some point in the near future. This practice, known in the art world as “flipping,” is at the center of Philbrick’s fraud.

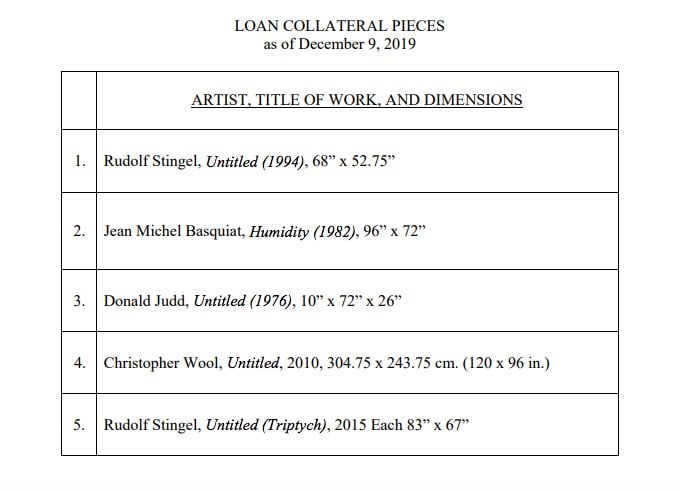

Not only did Philbrick then transfer ownership of the Basquiat to his own offshore company in Jersey, called Boxwood Green, he used it as part of a larger group of artworks pledged as collateral to lender Athena Art Finance in exchange for a nearly $14 million loan.

Philbrick arranged to lend the work to a major Basquiat exhibition at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo last fall. The loan was part of his concerted effort to boost the profile and potential resale value of the work. Unaware of the related Athena loan deals, Pesko agreed to the Tokyo museum loan, according to his filing.

Then everything fell apart—fast. By the time the Basquiat painting was hanging at the Mori Art Museum, the first of multiple lawsuits and asset seizure claims was filed against Philbrick, last October, and he quickly vanished. As the legal claims for this and other works mounted, panic among clients understandably ensued. Athena went directly to the Mori Museum and successfully claimed the painting. It is now sitting in an undisclosed storage location in New York and Athena wants to pursue a sale in order to recoup all or part of the money it lost.

A list of the artworks Inigo Philbrick used to secure a loan from Athena. Image via SCROLL (Supreme Court Records Online).

Late last month, Satfinance filed a “complaint in intervention” in federal court in the southern district of New York seeking rights to the Basquiat. The filing includes a minefield of allegations against Philbrick and, by extension, against Athena, including that the lender has refused to return Satfinance’s painting and is instead seeking an immediate sale of what it describes as “stolen property.”

The motion further asserts that Athena “was not a victim, but rather an enabler of Philbrick’s fraud,” including that it encouraged Philbrick to “assume control over the Jersey entity to effectuate the sham transfer” of the painting, which it describes as Satfinance’s property.

In mid-June, Philbrick was arrested on the South Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, where he fled after leaving the US last fall. He was brought to New York—with stops along the way in US prisons in Guam, Honolulu, and Oklahoma—after he was charged by the FBI and the US Department of Justice with an estimated $20 million fraud. Last month, in a telephone pre-trial hearing, he was officially indicted on charges of wire fraud and aggravated identity theft. He was denied bail and is being held in a correctional facility in New York. He has pleaded not guilty.

The Satfinance motion notes that the government’s criminal charges say Athena “encouraged” Philbrick to assume control over the offshore entity. It also alleges that Athena’s due diligence in extending a loan to Philbrick was “dismal.”

“Athena knew, or should have known, that [Philbrick] did not own the $30 million of artworks, including the [Basquiat], that it was purporting to pledge as collateral. Athena’s shoddy due diligence prior to originating the loan demonstrates its willingness to ignore this major ‘red flag’ to secure the sizable (and profitable) loan and grow its struggling book of business,” according to court papers.

The motion adds that even Philbrick himself was aware of the low burden of proof for the Athena loan. He was rejected from one other major art lender, which was not identified in the court filing, allegedly based on lack of credible proof of ownership of the artworks he proposed as collateral. Months later, after his fraud unraveled, the court papers state, he provided to an associate two pages of his hand-written Athena loan application, with an accompanying note saying: “Emailed you the financial disclosure document. You will die.”

Wendy Lindstrom, an attorney for Athena, countered some of these allegations, telling Artnet News that Philbrick “created his offshore entity in 2015, long before Athena provided him with a loan.”

“Regardless, global finance is regularly conducted through offshore companies; Satfinance is itself an offshore entity,” she added.

She also rejected the characterization of the company’s due diligence. “Athena performed rigorous due diligence in its loan underwriting process and has possession of all the artwork collateral for this loan,” Lindstrom said. “Satfinance never had possession of the Basquiat and continues to rely on representations from Philbrick.”

The Satfinance claims also include information about earlier deceptions regarding how Philbrick represented the Basquiat to Pesko. Some of those details are now part of the US government’s criminal charges against Philbrick.

For instance, Philbrick initially told Pesko that the Basquiat was being purchased for $18.4 million from a Pennsylvania-based company called SKH Management Corp. and furnished a purported bill of sale. The idea was to resell the painting within the course of a year for profit; Pesko would retain title while Philbrick would retain possession of the work and be responsible for costs related to insurance, storage, shipping, and marketing. But, in reality, Philbrick acquired the work—using Pesko’s $12.2 million payment—from Phillips for $12.5 million under a private-sale agreement, according to the court papers.

“Philbrick lied to [Satfinance] about the terms of the purchase,” the documents say. They also claim that Philbrick’s contract with SKH was fake and that the purported seller didn’t sign the contract for sale nor had SKH ever heard of the artist or Philbrick.

This appears to be connected to the FBI charges of identity theft, specifically that Philbrick provided Pesko with a contract from the Pennsylvania company. “In fact, the contract with the Pennsylvania company was fake,” according to documents.

Satfinance attorney Judd Grossman told Artnet News: “As alleged in the complaint, Athena’s refusal to return [Satfinance] stolen painting is rendered even more troubling by facts that have emerged demonstrating that Athena was not a victim, but rather an enabler of Philbrick’s fraud.”

Phillips New York offered the Basquiat painting at a November 2012 auction, according to the Artnet Price Database. It fell well short of the $12 million to $18 million presale estimate to bring a price of $10.2 million.