Art & Exhibitions

Is Braque Finally Coming Out of Picasso’s Shadow?

A major George Braque retrospective sets things right.

A major George Braque retrospective sets things right.

Coline Milliard

Georges Braque didn’t exactly lack public recognition in his lifetime. In 1955, aged 70, he was the first contemporary artist to officially enter the Louvre, with a commission for the ceiling of the Etruscan galleries. When he died in 1963, he was honored with a state funeral in the museum’s Cour Carré, one of only two artists ever to receive the accolade. The then-culture minister André Malraux compared him in his eulogy to Victor Hugo, the great hero of French literature.

But rather than preserving Braque’s legacy, this very official stamp of approval distanced the generation of artists and critics that came directly after him, eventually pushing the painter out of the art historical limelight. To those gearing up towards May ’68, he was, simply put, “an old-fashioned painter,” the deputy director of the Centre George Pompidou Brigitte Leal told artnet News. Somehow, the dusty image stuck. Leal has now curated a retrospective to set things right. Opening at the Guggenheim Bilbao on June 13 after it premiered at Paris’s Grand Palais last year, this major exhibition attempts to give Braque his deserved place, particularly in relation to his much acclaimed collaborator: Pablo Picasso.

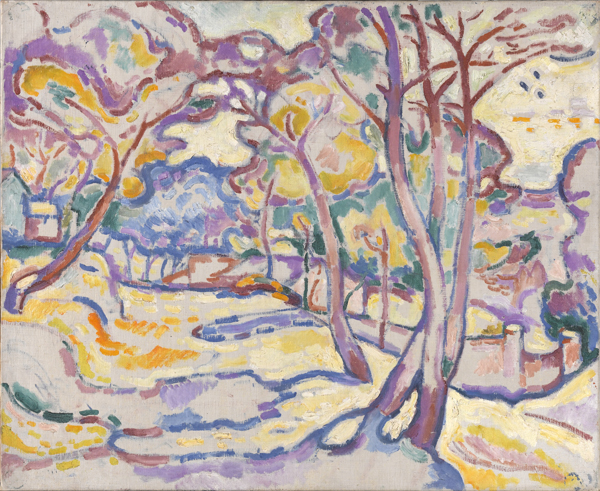

George Braque, Landscape in L’Estaque (Paysage de l’Estaque) (1906–1907)

Photo: © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Dist. RMN-GP / Georges Braque © VEGAP, Bilbao, 2014

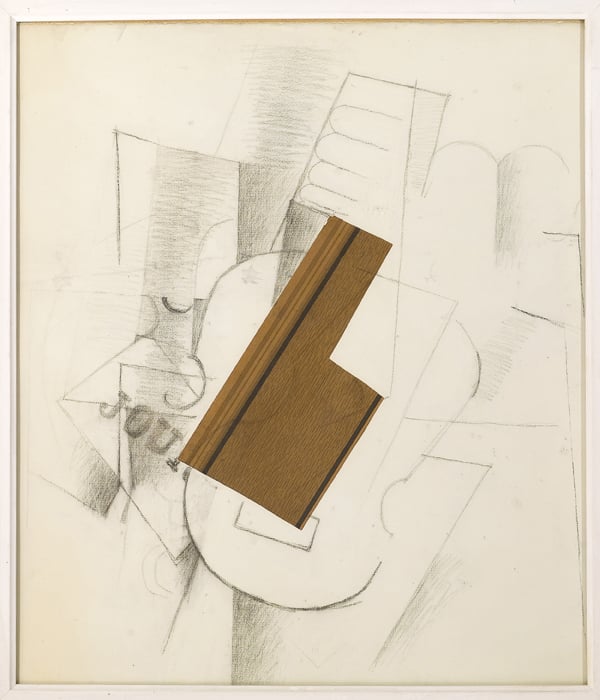

Such is the Spaniard’s stronghold on modernist art history, and particularly the birth of Cubism, that Braque’s involvement has often been relegated to a supporting act. He is seen as the second in the Picasso-Braque cordée, the two roped together in the climb towards Cubism. “We often omit to say that Braque was the inventor of the pasted papers (papiers collés) and of the transformation of the painting into the painting-object,” continues Leal. “He was a sort of leader [for the movement].” The pasted papers changed the course of the pictorial medium as much, if not more, than Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) that so impressed the young Braque when he first visited Picasso’s studio at the Bateau-Lavoir building with his friend poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

George Braque, Guitar (La Guitare) (1912)

Photo © Leiris SAS Paris, Georges Braque © VEGAP, Bilbao, 2014

The show is conceived as a Braque crash course. With over 250 works, it retraces the artist’s entire career, from his early Fauvist period—inspired by Henri Matisse and Paul Gauguin—all the way to the late landscapes that Leal calls “a resurrection of Van Gogh’s late works,” and which are painted with a knife. Although Braque always kept a strictly reduced palette and limited his range to a handful of topics which anchored him in the history of painting, the show demonstrates the artist’s immense stylistic versatility. For Leal, the paintings’ subjects bordered on irrelevant. In imagined dialogues with Chardin, Corot, and Cézanne, Braque tackled the very essence of painting. As he said himself: “the painter thinks in forms and colors.”

George Braque, Black Fish (Les Poissons noirs) (1942)

Photo © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Dist. RMN-GP, © VEGAP, Bilbao, 2014

Particular attention is given to little-known aspects of Braque’s oeuvre, including his painted plasters, his illustrations of Greek myths, and his collaboration with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The painter designed the costumes and stage sets for four productions: Les Fâcheux (1924), Zéphire et Flore (1925), Les Sylphides (1926) and Salade (1924), the rarely seen monumental curtain of which is a highlight of the Bilbao exhibition. The breadth of the display is an argument in itself. The scale of this exhibition is of the kind reserved to the greatest artistic minds of the 20th century. As curator Leal puts it herself, this isn’t a retrospective, but a true rehabilitation.