Law & Politics

Vigilante Art Hunter Thinks He Can Recover the Stolen Gardner Museum Paintings Within Months

Arthur Brand says he has a hot lead on the biggest heist in US history.

Arthur Brand says he has a hot lead on the biggest heist in US history.

Sarah Cascone

Solving the world’s most famous art heist, which saw 13 artworks stolen from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990, is no easy task. If anyone can do it, though, it’s Arthur Brand. The Dutch private investigator, responsible for the recovery of many high-profile stolen artworks, is currently following fresh leads in the cold case, and believes that the paintings’ recovery is imminent.

“It’s the holy grail. It’s the biggest case you can imagine,” Brand told artnet News. “You’re talking about $500 million in Vermeers and Rembrandts, and it’s been 27 years!” He believes that it could be a matter of months before the works are finally recovered. (Nina Siegel at Bloomberg first tracked him down.)

The Gardner Heist, still the largest property crime in US history, recently saw its $5 million reward for information leading to the artworks’ recovery in good condition, on offer since 1997, doubled to $10 million. The museum’s decision to up the reward came following a dead end involving a Virginia con man who falsely claimed to be in possession of the Gardner’s missing Vermeer, The Concert.

Vermeer, The Concert (circa 1664) is one of the works stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990.

Via Wikimedia Commons.

“People should come forward,” said Brand. “There is no need anymore to keep them hidden. You can get immunity, get the money and that’s it.”

If Brand’s name sounds familiar, it may be because you’ve read about his previous successes in combating art smuggling—Creators Project called him “an art world Indiana Jones in a suit.” Last year alone, Brand was instrumental in the return of paintings stolen from the Netherlands’ Westfries Museum in 2005 that had turned up in Ukraine, and a Salvador Dalí and Tamara de Lempicka stolen from the Netherlands’ Scheringa Museum of Realist Art in 2009.

At the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, empty frames now hands in the Dutch Room in place of Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee and A Lady and Gentleman in Black. Courtesy of the FBI.

Other successes include the recovery of 1,300-year-old illegally looted Peruvian artifacts and, separately, a number of bronze sculptures by Nazi artists, including two monumental horses, that had been lost since World War II. “I’ve cracked some huge cases,” Brand boasts. “Locating the [stolen art] is almost always the hardest part. You have to ask around in the underworld—sometimes it takes years—and then you have to negotiate.”

Brand is not officially working on the case with the FBI, but the agency is aware that he periodically receives tips about the case. He says that he is willing to serve as a go between with the government for anyone with relevant information who is willing to come forward.

Rembrandt’s Storm on the Sea of Galilee was among the works stolen from the Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990. The works have not been recovered despite extensive investigations.

While the FBI and Gardner museum security director Anthony Amore are presently of the belief that the stolen artwork remains in the US, Brand claims to have traced the paintings’ whereabouts to Ireland. He is currently exploring two tips in connection with the Netherlands.

But while Brand is optimistic, a recent report from the Boston Globe raised questions of whether key evidence in the case has been lost. Duct tape and handcuffs used by the robbers to tie up the museum’s security guards could potentially contain traces of the perpetrators’ DNA, but have allegedly gone missing.

“Back in 2010 evidence was sent down to the FBI laboratory for DNA analysis and that analysis was completed,” FBI spokesperson Kristen Setera told artnet News in an email. “Beyond that, we are going to decline comment because we do not talk about evidence in pending cases.”

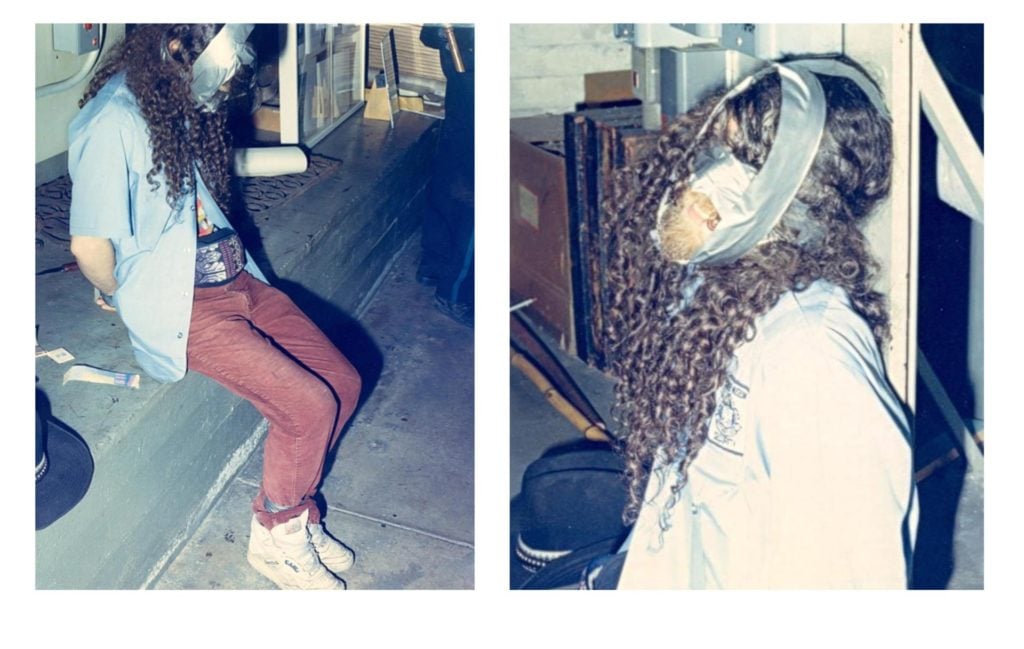

Richard Abath handcuffed and duct-taped in the basement of the Gardner Museum. Courtesy of the Boston Police.

In 2013, the FBI, US Attorney’s office, and the museum held a press conference announcing that they had identified the people responsible for the initial heist. The two robbers were later named as George Reissfelder and Lenny DiMuzio, and were said to have committed the burglary at the behest of Carmello Merlino. All three men are now dead.

Also under investigation is alleged Connecticut mobster Robert “Bobby the Cook” Gentile, long believed to have had knowledge of the crime. The FBI raided Gentile’s home in 2016, but found nothing. Now in ailing health and reportedly near death, he has maintained ignorance of the heist, even while pleading guilty on unrelated gun charges.

“The investigation has had many twists and turns, promising leads and dead ends. It has included thousands of interviews and incalculable hours of effort,” Setera added. “There is no part of the world the FBI has not scoured following up on credible leads.”

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

“In most cases after two or three years, I’m the only in the world who’s working on a case,” said Brand, who has nothing but praise for the official investigation. “They are doing a great job. On almost a monthly basis they bring something new out—it’s quite exceptional.” Finding the missing paintings is not a competition, he insists, and everyone involved just wants their safe return, regardless of how it is secured.

“It’s not about who did it anymore,” added Brand, noting that he agrees with the FBI that those originally responsible for the heist are now dead. “It’s about getting these pieces back. It’s world heritage!”

And what of speculation that the artworks must have been destroyed in the over quarter century since they were last seen?

“I have some leads that confirm that they still exist,” Brand insisted. “You never know of course; they could have been destroyed—but it would be a stupid thing with such a huge reward!”