Museums & Institutions

Before the Notorious Art Heist Eclipsed Her, Isabella Stewart Gardner Made Headlines as ‘America’s Most Fascinating Widow.’ Here’s Why

A new biography reveals the unconventional woman behind the famed Boston museum.

A new biography reveals the unconventional woman behind the famed Boston museum.

Sarah Cascone

Nearly 100 years after her death, on July 17, 1924, the fame of Isabella Stewart Gardner endures, her name immortalized thanks to her eponymous Boston museum. The institution, of course, is home to many masterpieces—and is best known for those that are missing, stolen during a daring 1990 heist likely orchestrated by the Italian mafia.

But for all the headlines generated by the fate of Rembrandt van Rijn’s only seascape, Johannes Vermeer’s The Concert, and the other missing works—not to mention the $10 million reward for their return—you might be surprised to realize you know very little about the woman herself.

Luckily, the museum has just released Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life, a new biography about Gardner, written by its curator, Nathaniel Silver, and assistant curator, Diana Seave Greenwald.

Gardner was in some ways quite a private person—little of her own writing survives, in large part because she asked friends to burn her correspondence, making it hard to know her views on slavery, women’s suffrage, and other pressing issues of her day.

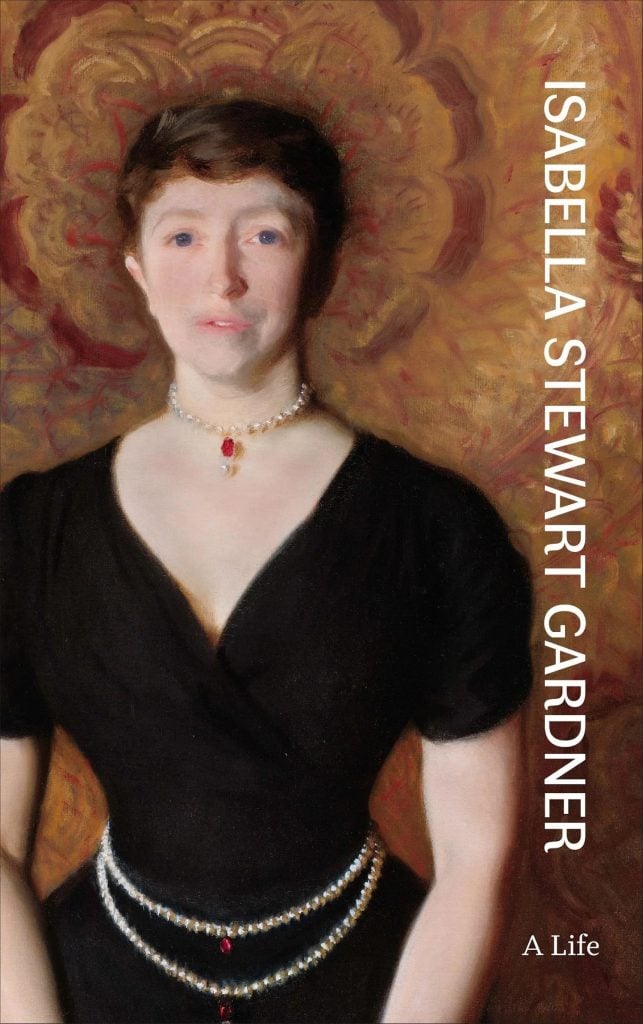

John Singer Sargent, Isabella Stewart Gardner (1888). Collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

But as a larger-than-life public figure who helmed a major construction project to open one of the first private museums in the U.S., Gardner left behind enough records to help her biographers piece together a fascinating life story of a woman who defied convention to create an enduring legacy.

Here are six things you might not know about the pioneering collector and museum founder.

A 1899 New York Journal piece on “The Latest Whim of America’s Most Fascinating Widow” includes a photo of a woman who is decidedly not Isabella Stewart Gardner. Collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Something of a Kim Kardashian of her day—in that she was rich, desirable, and endlessly fascinating to the press—Gardner saved hundreds of newspaper clippings recounting her exploits.

These weren’t always accurate. A 1899 New York Journal piece on “The Latest Whim of America’s Most Fascinating Widow,” about her plans for the museum, featured a photo of a different, unknown woman. But they could be delightful. Four papers reported on the special treatment she received at the Boston Zoo, where she was allowed to walk animals like Rex the lion on a leash—dressed to the nines the whole while, naturally.

This attention from the press cut both ways, elevating Gardner’s stature but also characterizing her as frivolous and eccentric, rather than recognizing her important cultural contributions.

Gardner carefully cultivated her personal image, and scandalized society with her 1888 portrait by John Singer Sargent. The painting accentuates her hourglass figure in a hip-hugging black dress with a plunging neckline that was quite revealing for the day. At the request of her husband, John Lowell “Jack” Gardner Jr., she hung the controversial work in a gallery that remained private during her lifetime.

Isabella Stewart Gardner and her son, Jackie, (1864). Photo by John Adams Whipple. Collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Gardner dealt with death throughout her life, starting when she was 14, with the death of her 12-year-old sister. Her two younger brothers also died young, in their mid-20s. And just five months after her 1860 marriage to Jack, the couple buried a still-born infant. Their only living child, named after his father, died just shy of his second birthday. Then, at the same time her sister-in-law and close friend Harriet Sears Amory Gardner died a few months later, Gardner miscarried again.

Building a major art collection with her husband helped Gardner recover from a deep depression. And though they never had another child of their own, the couple adopted their three orphaned nephews after Harriet’s husband, Joseph Peabody Gardner, died in 1875. Sadly, the oldest boy, Joseph Peabody Gardner Jr. also died young, at just 25.

And tragedy struck again as the couple began preparations to open a private museum showcasing their holdings. Jack died in 1898, at 61 years old. (Gardner, just three years his junior, would live until age 84.) In her grief, Gardner threw herself into the museum, creating a memorial to Jack, Jackie, and Joseph Jr. in the galleries. To this day, a small case displays their photographs alongside her own, in tribute to her lost family.

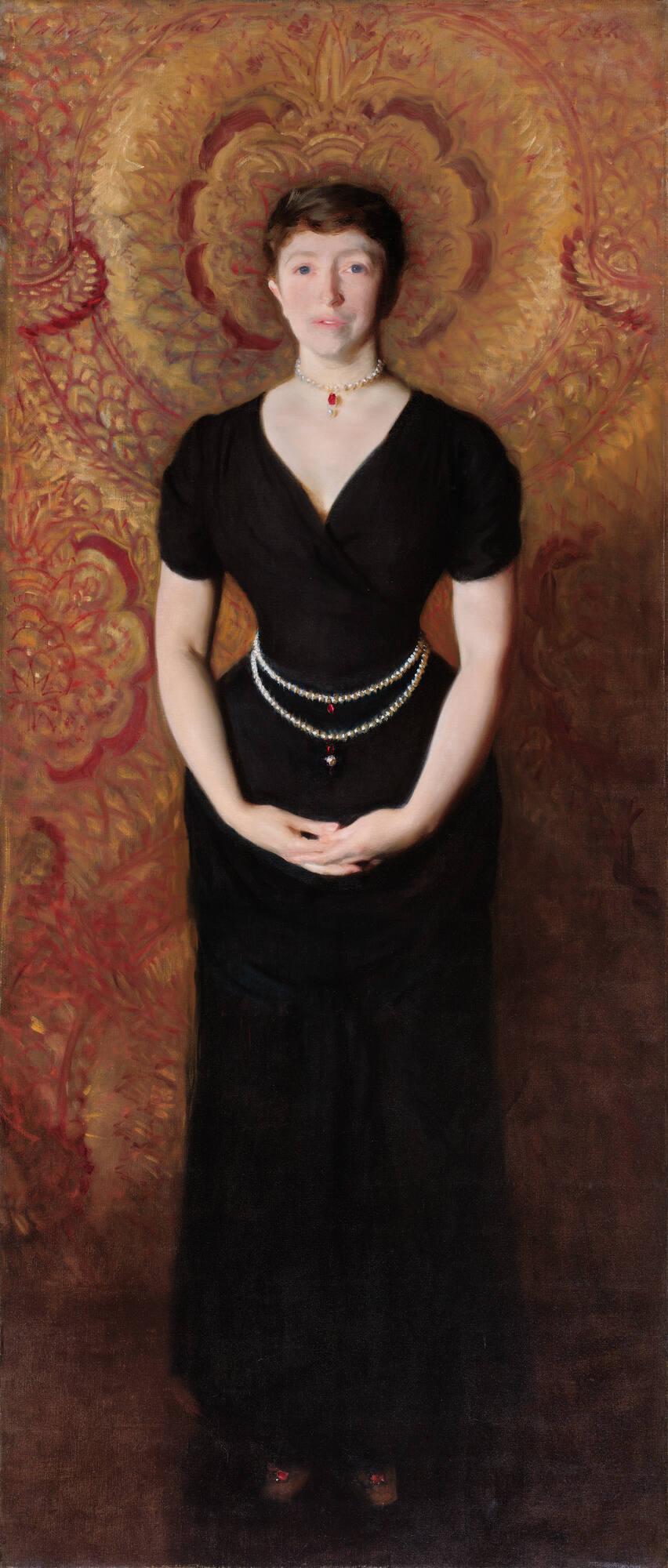

A photo of the Sistine Chapel from Isabella Stewart Gardner’s travel album from her 1895 trip to Italy. Collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

In the aftermath of Gardner’s second miscarriage, to help lift her depression, a doctor suggested Jack take her on a trip to Europe. The ensuing tour of Scandinavia, Russia, and Central Europe proved a turning point in their lives, marking the beginning of their art collection.

Educated in Paris as a teenager, Gardner was fluent in French and later learned Italian and Spanish. She eventually made 13 international voyages to 38 countries, picking up everything from Chinese antiquities to Romanesque sculpture and Flemish tapestries to Dutch Golden Age masterpieces, Italian Renaissance art, and Old Master drawings along the way.

Gardner memorably bought The Concert at a Paris auction, arranging a secret signal with a dealer who bid on her behalf, instructing him not to stop until she lowered her handkerchief. The two outbid Paris’s Louvre and London’s National Gallery to take home the trophy.

In addition to making major acquisitions for her art collection during her travels, Gardner also took careful note of different architectural styles, which she blended to delightful effect in designing her museum.

The building was clearly influenced by Venetian palazzos like the one she rented in the Italian city, with a courtyard surrounded on three sides by covered walkways, inspired by medieval cloisters.

Gardner even incorporated historic architectural elements shipped from overseas into the construction—a groundbreaking first for a U.S. museum.

William Ward, Mary Queen of Scots Under Confinement (1793). Collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

To this day, the museum has a case of objects supposedly linked to the Scottish monarch, a familial devotion for Gardner as a Stewart. Too bad the queen’s family spelled it Stuart, and genealogists haven’t been able to find any link between Gardner and a royal lineage.

Gardner was right that she was of Scottish origins, by way of her father’s father, dry goods merchant James Stewart, who immigrated to New York City. His son, David Stewart, went on to co-own a company that imported cotton and linen textiles from Scotland and Ireland—a business that likely benefitted from the labor of enslaved people.

Later, Stewart moved into the profitable field of coal and iron mining, leaving Gardner $2.75 million (the equivalent of $78 million today) upon his death in 1891. Combined with Jack’s family fortune, that money became the foundation on which Gardner’s museum was built.

The courtyard at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo by Sean Dungan, courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

In a reminder that the more things change, the more they stay the same, Gardner ran afoul of tax law while importing valuable art from Europe—a major concern of collectors to this day. (There’s a reason leaks like the Paradise, Pandora, and Panama Papers always reveal a web of shell companies and other shady financial transactions related to major works of art.)

In Gardner’s case, she hadn’t paid the U.S.’s 20 percent tariff, believing she was exempt because the museum was a charitable organization open to the public.

But the Fenway Court, as it was called during her lifetime, only opened for a couple of weeks at a time, once in the spring, and again around Thanksgiving. In 1904, the Treasury Department ruled that she owed the IRS back taxes, and levied a $200,000 fine. (The issue of whether private museums with limited public access deserve tax breaks remains contentious over a century later.)

Titian, The Rape of Europa (ca. 1560–62). Collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Gardner likely met Bernard Berenson at Harvard University, where she was a member of the Dante Society. She helped pay for Berenson’s studies in Europe after he was rejected from a travel fellowship.

The trip was instrumental in transforming the young art historian into a leading scholar of Italian Renaissance art. In turn, it was Berenson that encouraged Gardner to become one of the first U.S. collectors to invest in works from the period.

In the years before she began work on her museum, Gardner bought 26 artworks through Berenson. Among them were the nation’s first paintings by such major artists as Raphael, Titian, Sandro Botticelli, and Fra Angelico—Titian’s Rape of Europa chief among the highlights.

The relationship was not without its speed bumps. In what might today be considered a conflict of interest for a scholar, Berenson made quite a profit on these deals, sometimes nearly doubling a work’s initial price when offering it to Gardner. (A practice that can turn litigious in the 21st century.)

She once wrote to him noting that others had warned her that “you have been dishonest in your money dealings.” On the whole, however, it was a fruitful relationship for both parties, allowing Gardner to build an incredible collection by the standards of any era.

More Trending Stories:

Click Here to See Our Latest Artnet Auctions, Live Now