On View

A New Exhibition Explores How a Medieval Printmaker Transformed the Artist’s Copyright

The show at the Chazen Museum of Art charts the influence of Israhel van Meckenem.

The show at the Chazen Museum of Art charts the influence of Israhel van Meckenem.

Adam Schrader

A new exhibition at the Chazen Museum of Art in Wisconsin will showcase how a Medieval goldsmith working at the advent of European printmaking raised questions about copyright and branding that still resonate today.

“Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s 15th-Century Print Workshop” explores the life and impact of Israhel van Meckenem, whose prolific work during the latter half of the 15th century shaped print production in Northern Europe. Besides producing a vast quantity of Old Master prints, he would also engrave his own compositions, which depicted everyday German life with an intricate hand. The show will feature more than 60 objects, including his engravings of contemporaneous artists such as Master ES and Albrecht Dürer.

“Israhel is a particularly compelling early European printmaker from a present-day perspective,” said curator James R. Wehn. “He does some things early on in the history of European print that make him special.”

For example, Israhel created what is considered the first printed self-portrait, which Wehn said “really shows the autonomy” that printmakers had to promote their workshops at that time. The museum will include a double self-portrait with his wife in the show as what Wehn termed “an ancestor of the selfie.”

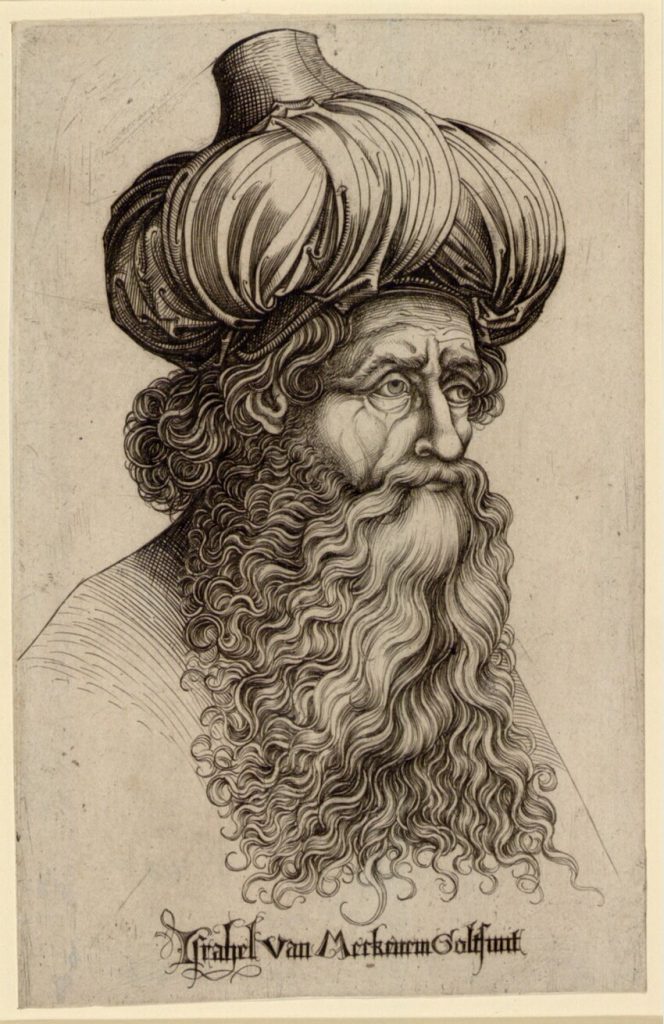

Israhel van Meckenem, Head of a Man Wearing a Turban (date unknown). Photo courtesy of Albertina Museum via Chazen Museum

But perhaps more importantly, Israhel experimented with his identity as a brand trademark, becoming one of the first printmakers to start signing his work, not least with an elaborate script to mirror the ornate text in illuminated manuscripts. And he was doing so on works that, by today’s standards, would been considered plagiarized.

“Modern audiences will find the paradox amusing. While he’s signing a lot of his prints, he’s also copying them from other artists and other engravers who are making prints. He’s taking that image, copying it, and putting his own name on it,” Wehn said.

Medieval entrepreneurs like Israhel realized they need to distinguish themselves from competitors. This idea continued with Albrecht Dürer, among the following generation of German printmakers, whose life overlapped with van Meckenem’s.

“In fact, Israhel copied four of Dürer’s earliest engravings. We don’t know whether Dürer was specifically aware that he copied those images,” Wehn said. “There is some indication he was familiar with Israhel’s work, because he does his own copying of a print by Israhel, but changes the composition dramatically.”

Dürer did attempt to curb plagiarism by getting a privilege from the Holy Roman Empire that he could put on his prints. He also brought complaints to local governments against artists who copied him. In one known case, the Venice city council allowed an engraver Marcantonio Raimondi to copy Dürer’s image, but without Dürer’s brand. In another in Nuremberg, the city council made a similar ruling, which set the precedent that it is okay to copy an image, but not to use the trademark of the artist.

“What this tells us is that, at that time, the concept was that labor and materials are valued. The generation of the image is about labor and materials. And so, it’s okay to plagiarize,” Wehn said. “But it’s not okay to forge.”

Wehn called the career of Israhel, along with Dürer, the seed that starts “centuries worth of efforts of creating copyright law and intellectual property that bring us to today.” He also highlighted “interesting parallels” with the artist rights debates now swirling artificial intelligence.

“The introduction of this capability and this new medium in the marketplace has an effect on cultural expectations, and raises questions about who’s the author and what is intellectual property,” Wehn said. “Do we value what is invented by the human mind? Or do we value the work of making the image?”

Israhel van Meckenem, The Five Foxes, (1485–95). Photo courtesy of Art Institute of Chicago, Clarence Buckingham Collection, via Chazen Museum.

The Chazen exhibition will display multiple copies of the same pictures, printed by Israhel and others for comparison. There is even one case presented in the show where a print by the esteemed engraver Martin Schongauer was copied by another artist. That plate was somehow acquired by Israhel, who reworked it, scraped off the previous owner’s name, and replaced it with his own initials.

“We can understand that the engraved copper plate was valuable. It could change hands, it could be ascribed to a different workshop and reissued to make money,” Wehn said. “But what’s special about that is that we’ll have all three of those images.”

“Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s 15th-Century Print Workshop” is on view at the Chazen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, 800 University Ave, Madison, December 18 through March 24, 2024.

More Trending Stories:

Conservators Find a ‘Monstrous Figure’ Hidden in an 18th-Century Joshua Reynolds Painting

A First-Class Dinner Menu Salvaged From the Titanic Makes Waves at Auction

The Louvre Seeks Donations to Stop an American Museum From Acquiring a French Masterpiece

Meet the Woman Behind ‘Weird Medieval Guys,’ the Internet Hit Mining Odd Art From the Middle Ages

A Golden Rothko Shines at Christie’s as Passion for Abstract Expressionism Endures

Agnes Martin Is the Quiet Star of the New York Sales. Here’s Why $18.7 Million Is Still a Bargain

Mega Collector Joseph Lau Shoots Down Rumors That His Wife Lost Him Billions in Bad Investments