Art & Exhibitions

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s Istanbul Biennial Makes Political Statements With Outstanding Art

The biennial also focuses on the Armenian Genocide.

The biennial also focuses on the Armenian Genocide.

Amah-Rose Abrams

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev at the press conference for the 2015 Istanbul Biennial

Photo: courtesy Istanbul Biennial

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s Istanbul biennial, “SALTWATER: A Theory of Thought Forms,” opened with speeches and song as the art world gathered eagerly to hear what the famed curator had to say, and how this hotly anticipated biennial would come together.

This is Christov-Barkagiev’s first major exhibition as curator (or as she prefers to be called, draftsperson) since the rapturously received Documenta 13 in 2012.

The salt water theme is multilayered in its meaning, drawing on salt water as a metaphor that ranges from the sea and the Bosphorus of Istanbul to the flow of peoples across the world, the waves of history and trauma in the world, and in the history of the ancient city of Istanbul. Salt water both heals and corrodes, Christov-Bakargiev told the press, explaining rather superfluously that water flows, creates knots and eddies, passage and barriers.

“The one reason I am not in politics but in art is because I feel that art has a possibility of shaping the souls of people, and transforming the opinions of opinion leaders who are also then in a trickle-down effect shaping what will be the policies of government,” emphasized Christov-Bakargiev in her opening speech. “I am skeptical and I am a skeptic,” she added, quoting from the Bible.

Three or Four Shades of Blue (2015) Theaster Gates, installation view at the Istanbul Biennial 2015

Photo: courtesy Istanbul Biennial

Theaster Gates (who can really sing!) and Adrian Villar Rojas opened the event with musical performances. Gates sang Walk With Me, a cappella, and Rojas performed an acoustic version of Erasure’s A Little Respect, accompanied by an acoustic guitarist and drummer.

As soon as the applause echoed across the Italian School and Embassy, where the press conference took place, everyone present, including Hans Ulrich Obrist and Nicholas Serota, scattered into the nearby twisting streets of Istanbul to see what the biennial had in store.

First up was Un/fit for Feeling (2015), by British artist and poet Heather Phillipson, whose work was a letter to the human heart comprised of sculpture, film, and installation. The core of the piece was what it meant to be “heartfelt,” as the heart as an organ cannot feel. We drown in a sea of love, in a sea of red.

The Salt Traders (2025) Anna Boghiguian

Photo: courtesy the Istanbul Biennial

There is also an Armenian theme to the biennial, marking a century since the Armenian genocide at the hands of the Turkish government of the time. Among sites open to visitors is the building of Hrant Dink, the Turkish-Armenian journalist who founded bilingual paper Agos, and was assassinated in 2007. Also, the Museum of Innocence author and Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk is hosting two paintings by Abstract Expressionist artist Arshile Gorky, who survived the massacre in 1915.

Theaster Gates’ work, also to be found in the narrow streets that surround the Italian Embassy, comprises different elements, all linking back to the city. “I built a workspace that allows me to learn and care for these fragments of Turkish history that in some ways, when I was asked to be a part of the biennial of Istanbul, I really struggled to imagine my connection to,” Gates told artnet News.

“But the more I considered its history and the more I started to mine the objects that I had, the more I realized that there were all these connections that were not on the surface,” he explained. “So, I started to mine my collections and found a Turk who had started Atlantic Records.”

Gates realized that he had over 200 soul and jazz records from the legendary label started by Ahmet Ertegun. The work also shows slides of Mohammedan sculpture and an intricate 17th-century Iznik bowl. Gates will make and re-make versions of the ceramic.

“The bowl is really the heartbeat of the space,” Gates explains.” Over the next few weeks I will ponder this bowl as a way of pondering Turkey, and that maybe through the recreation of this bowl I might learn something.”

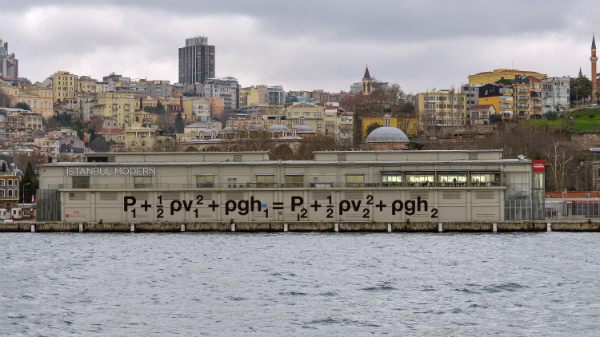

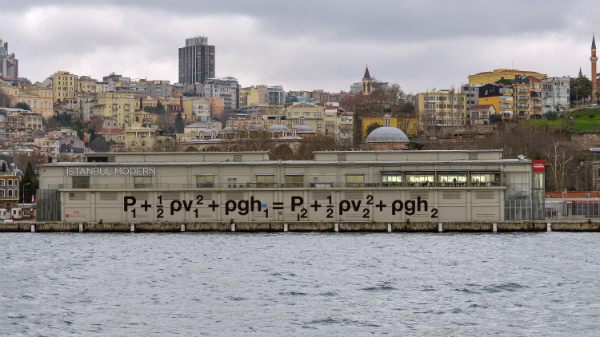

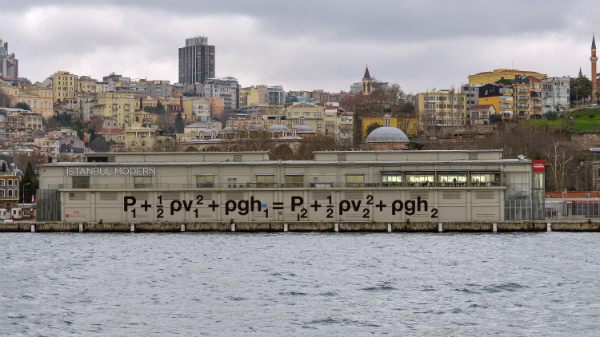

Hydronamica Applied (2015) Liam Gillick

Photo: courtesy the Istanbul Biennial

At Istanbul Modern, Liam Gillick’s formula used to create a pulse, or flow, is unmissable on the waterside of the museum, visible to all who look at the city from the other side of the Bosphorus.

Then off to an amazing performance surrounding works exploring Aboriginal maps and the notion of reading of their artworks as messages—messages which in some cases saw the restoration of land rights in Australia. The theme of migration, currently a humanitarian and political crisis reaching devastating effects in the region, is on people’s minds, in the artworks, and in the media.

One of the most striking works of the biennial is the installation work by Egyptian painter Anna Boghiguian at the Galata Greek Primary School. The site was chosen, in keeping with the theme, as it is no longer a school due to longstanding conflicts between Greece and Turkey, so that there are no Greeks left to attend it. The main hall of this impressive space is filled with painted Egyptian sails which hang from the ceiling.

This work explores the nature, history, and science of salt, from the scientific formulas and maps of the world that decorate the draped sails to the piles of salt from Ethiopia, Pakistan, and Turkey.

Saltwater Heart (2015) Pinar Yoldas

Photo: courtesy the Istanbul Biennial

As the heat intensified, we crossed the city to Kucuk, Mustufa Pasa Hammam, and Wael Shawky. Shawky’s work, displayed on a huge screen bathed in blue light, is installed in a 14th-century hammam, one of the oldest buildings in Istanbul. The work is the final installment of his film trilogy, the Cabaret Crusades, entitled Cabaret Crusades: The Secrets of Karbala (2015).

“I’m totally interested in societies in transition,” Shawky told artnet News. “And in the idea, or the dream of development, so I’m always running after this topic, really.”

“The history of the crusades is like a dream for Pope Urban II, who launched the crusades in 1095, a religious dream. I’ve worked on this series since 2010 and I finished this year with the third film, which I am showing here.”

The Cabaret Crusades: The Secrets of Karbalaa (2015) Wael Shawky

Photo: courtesy the Istanbul Biennial

The work is the longest and the most complex of the trilogy. It tells the story of the crusades from 1146 to 1204 and starts with a flashback to the battle of Karbala (in present-day Iraq) which caused the split creating Sunni and Shia Muslims. “[The film] ends with the fourth crusades that is mainly political rather than religious.”

The nature of this work could not speak more to the theme of the biennial, spanning history, perception, cultures and exploring division, and is one of the most successful works on view.

The Most Beautiful of All Mothers (2015) Adrian Villar Rojas

Photo: courtesy the Istanbul Biennial

The second day we took to the islands in the Bosphorus. Christov-Bakargiev’s vision and salt water theme take in everything from the Black Sea to the Princes’ Islands in the Marmara Sea surrounding Istanbul.

The island of Büyükada has an otherworldly quality to it. Stepping off the sea bus, one enters into a world of horse-drawn carriages and French colonial style mansions. It is behind these whitewashed shutters and floral hedges that the rest of the biennial works are installed.

Well, not all of them. As we disembarked from one boat we embarked on another, which held two very different installation works.

Pinar Yoldas’s conceptual work, on the deck of the boat, used the seawater to explore themes of pollution and nature. Usually working with biological processes reapplied on a small scale, Yoldas was persuaded by Chrtistov-Bakargiev to upscale her vision, and created a sculptural system of clear tubes draped over a metal frame. The size of the boat is comparable to that of a blue whale, 30 to 40 meters in length; the clear blue water that is pumped through flows at the same rate as a whale’s heartbeat.

Inside the boat is the submerged universe of Markus Lutyens, combining his techniques of histories and hypnosis.

Still From Hisser Ed Atkins (2015)

Photo: courtesy the Istanbul Biennial

Next up was a new work by Ed Atkins, Hisser (2015), which was packed with expectant artists, critics, and curators all sweltering in the intense heat. Viewers enter into a Hitchcock-esque abandoned house full of empty rooms and abandoned furniture. Upstairs, Hisser plays on a huge screen. The work is inspired by the true story of a man whose bedroom fell into a sinkhole and was never found.

“I’m sorry I didn’t know,” the digitally recreated man says and sings as he lies in bed and then walks, bruised, across an empty screen.

Another work that was packed with eager beavers was Rojas’. You would be hard pushed to feel nothing walking through the wrecked shell of Trotsky’s house. Exiled from Russia, he lived on the island for four years at the end of the 1930s.

On a steep and rocky route from the road to the sea, the rotten and rusted shell of the house gives way to the blue waters and the huge sculptures Rojas installed, emerging from the sea like relics of a bygone age.

The city of Istanbul has a magical charge due to its history and its location. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev has captured both this and the mood of the time.

“SALTWATER: A Theory of Thought Forms,” the 14th Istanbul biennial, runs from September 4 to November 1, 2015.

Related stories: