The Italian city of Brescia went ahead with the opening of a solo exhibition of work by Chinese-Australian dissident artist Badiucao on Saturday, despite protest from Beijing.

The Chinese Embassy in Rome had sent an email to Brescia Mayor Emilio Del Bono last month alleging the exhibition was “full of anti-Chinese lies,” and that the artworks “distort the facts, spread false information, mislead the understanding of the Italian people and seriously injure the feelings of the Chinese people,” according to the Giornale di Brescia.

The embassy demanded the cancellation of the show, titled “China Is (Not) Nearby,” at Museo di Santa Giulia. Moving forward with the exhibition would affect the friendly relations between the two countries, the embassy threatened.

“The letter was very intimidating. It was not expressing the concerns of the Chinese government. It was a direct order to the museum demanding that the show be cancelled,” Badiucao told Artnet News.

Chinese dissident artist Badiucao (C), with Mayor of Brescia, Emilio Del Bono (2ndL), vice-Mayor of Brescis, Laura Castelletti (3rdR), President of Fondazione Brescia Musei, Francesca Bazoli (4thR), cuts the ribbon on the opening of an exhibition of his artworks on November 12, 2021 entitled “China is (not) near — works of a dissident artist”, at the Santa Giulia museum in Brescia, Lombardy. Photo by Piero Cruciatti/AFP via Getty Images.

The artist, who has faced government pushback for his work critiquing Chinese human rights abuses in the past, was not surprised by the response. “This is my daily routine. Any time I do something, the Chinese government will try to stop it,” Badiucao said.

But he was surprised by the city of Brescia’s response. The city and the Brescia Musei Foundation, which runs the institution, refused to censor the artist’s work.

Brescia has “always championed freedom of expression and would continue to do so,” the mayor told the New York Times. “Art should never be censured.”

“I’m very glad the local government and the museum held the line to to defend freedom of speech,” Badiucao said. “They showed their solidarity with me.”

A former assistant to Ai Weiwei who now lives in Australia, Badiucao was supposed to have his first solo show in 2018, in Hong Kong. Two members of the Russian art activist group Pussy Riot took part in a pro-democracy panel meant to accompany the exhibition, but the show was cancelled. (Some of those works are now on view in Brescia.)

Chinese dissident artist Badiucao poses next to his artwork entitled “Watch, 2021” on November 12, 2021 at the exhibition “China is (not) near — works of a dissident artist”, opening at the Santa Giulia museum in Brescia, Lombardy. Photo by Piero Cruciatti/AFP via Getty Images.

At the time, the artist was still working anonymously. In 2019, Badiucao revealed his face in the documentary film China’s Artful Dissident.

“China Is (Not) Nearby,” which was originally scheduled to open last year, follows the museum’s 2019 exhibition of work Kurdish artist Zehra Doğan made during her three-year incarceration in a Turkish prison. Badiucao’s show is part of Brescia’s Peace Festival (through November 26).

“The aim of the festival is to promote human rights, freedom of expression, and peace,” Badiucao said. “The biggest inspiration for me is the human rights abuse happening in China.”

The artist believes the power of the growing Chinese market has discouraged institutional venues from engaging with his work.

“Authoritarian governments are always trying to control artists,” Badiucao said. “The Chinese government is using the art market as a tool to stop artists like me.”

“I think a lot of Chinese artists shamefully act as pawns for Beijing, serving narratives on behalf of Chinese government interests, promoting the soft power of the Chinese Communist party,” he added. “The Chinese government is worried that more artists will follow the path of great artists like Ai Weiwei and try to convey our own ideas about what is going on in China to the rest of the world—they’re really scared of the power of art.”

A visitor takes photos of “Winnie the Trophies, 2017”, an artwork by Chinese dissident artist Badiucao at the Santa Giulia museum in Brescia, Lombardy. Photo by Piero Cruciatti/AFP via Getty Images.

The Brescia museum show has been the first opportunity for Badiucao to showcase work beyond the political cartoons and other illustrations he has long shared on social media. Works in the show include 64 paintings of a watch the Chinese government gave to soldiers who helped quell the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, each made using his own blood.

The 89.6 watches—so named for their inscription reading “89.6 to commemorate the quelling of the rebellion”—are rarely seen in public. When one went up at auction in the U.K. last year, Badiucao protested the sale. which he felt presented the evidence of a massacre as a luxury good. It was ultimately canceled, and Badiucao was able to acquire another of the watches as a gift, using it to create this body of work.

Other pieces include sculptures of Molotov cocktails made instead from soy sauce bottles, posters critiquing the upcoming Beijing Winter Olympics, and paintings featuring Winnie the Pooh, used in China as a mocking reference to President Xi Jinping. Badiucao is also staging performances during the show, reading from a diary of a Wuhan resident, written during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, while sitting in a torture throne he purchased online.

The artist expects further harassment on the part of the Chinese government—Chinese nationalists, he claimed, already disrupted a talk he gave at the Bologna Academy of Fine Arts. But for Badiucao, the risk taking inherent to his art is worth it.

“Why are we making art?,” he asked. “Is it to be famous or rich, or is it because we believe in art as something that can uphold humanity and protect us from oppression?”

See more from the show below.

Badiucao’s exhibition “China Is (Not) Nearby” at the Museo di Santa Giulia in Brescia. Photo courtesy of the Fondazione Brescia Musei.

Badiucao’s exhibition “China Is (Not) Nearby” at the Museo di Santa Giulia in Brescia. Photo courtesy of the Fondazione Brescia Musei.

Badiucao’s exhibition “China Is (Not) Nearby” at the Museo di Santa Giulia in Brescia. Photo courtesy of the Fondazione Brescia Musei.

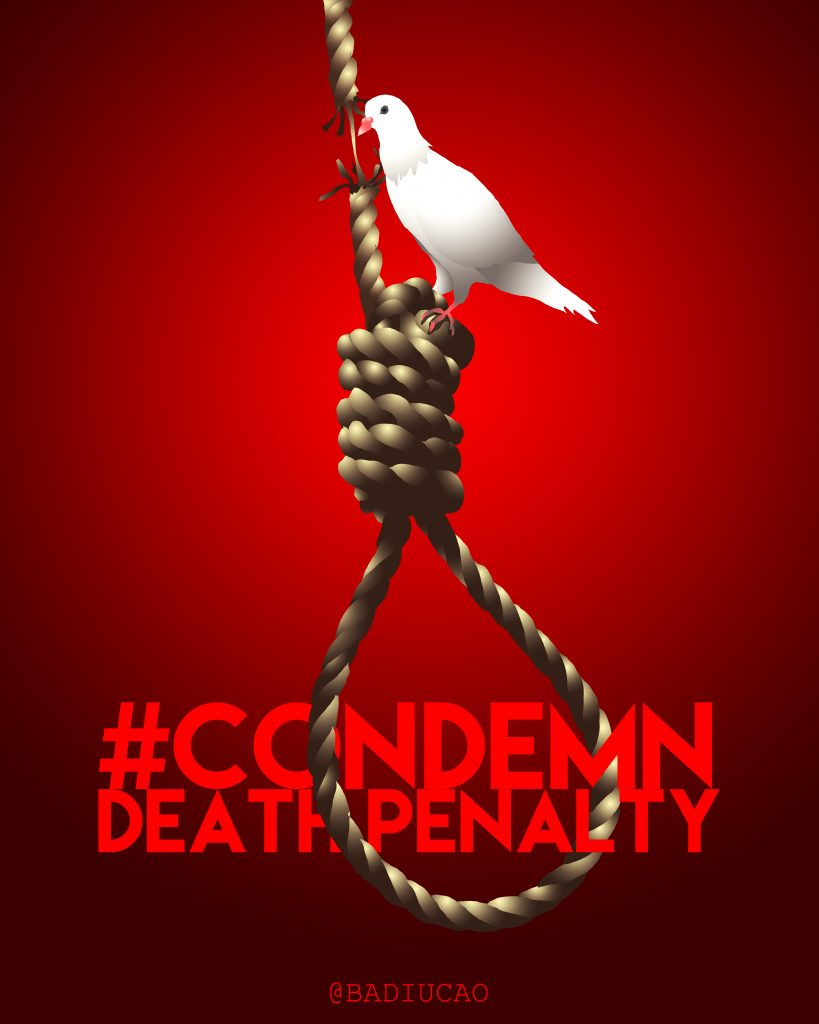

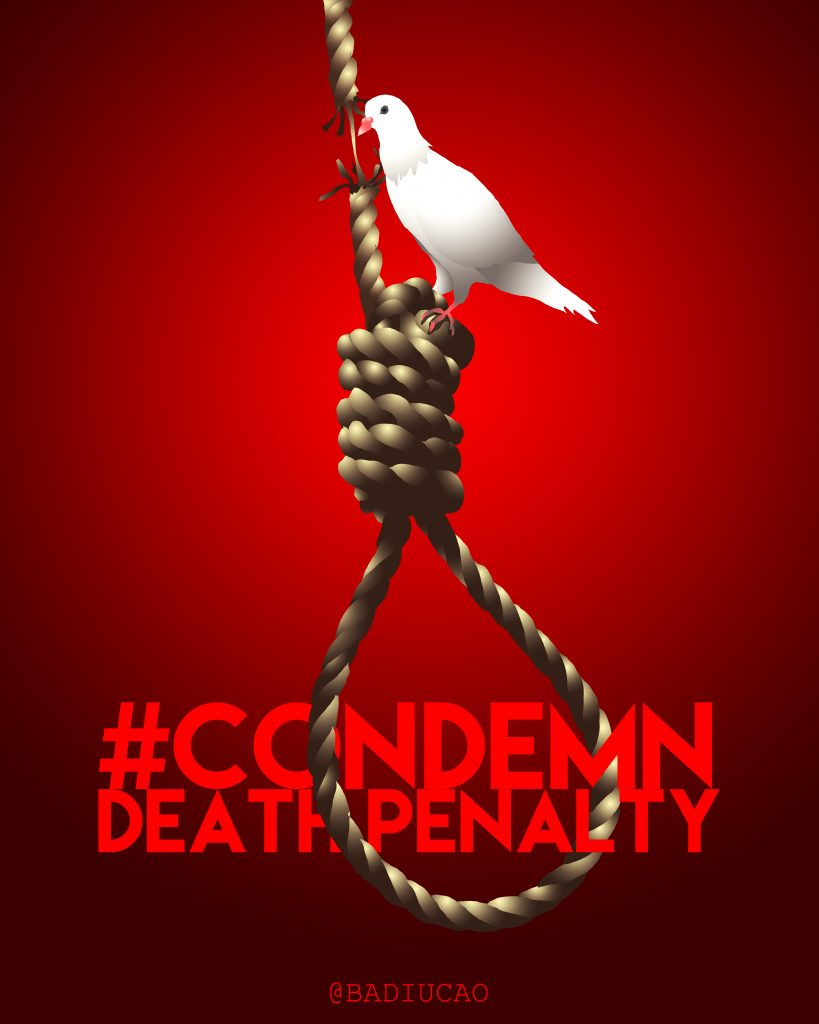

Badiucao, Condemn Death Penalty (2021). Image ©Badiucao.

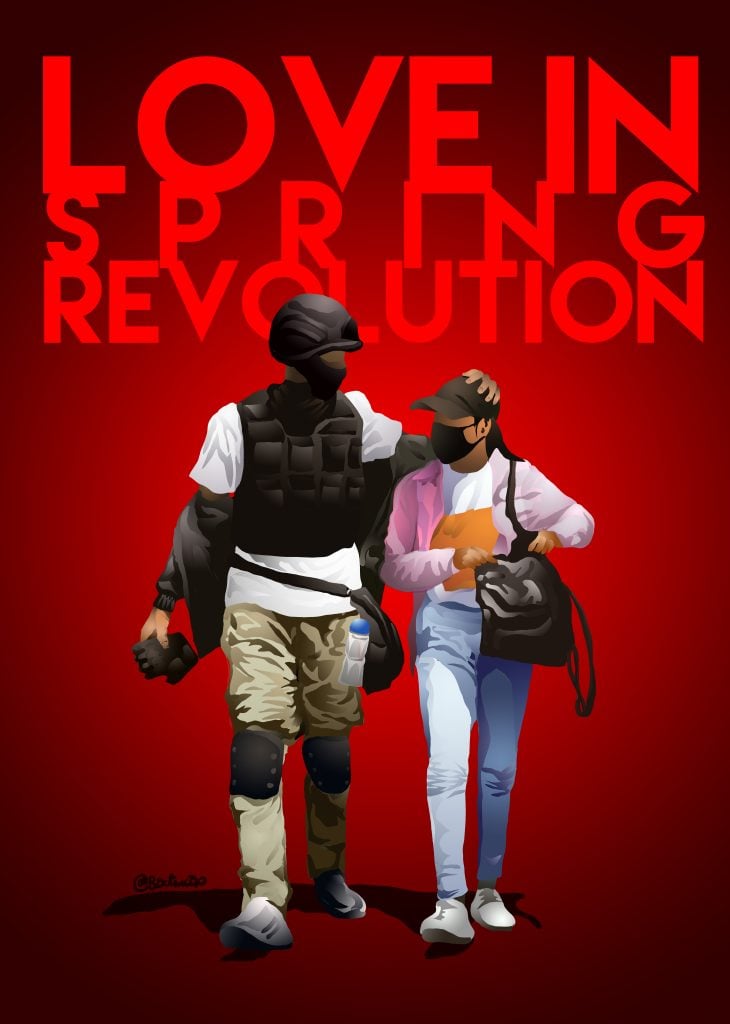

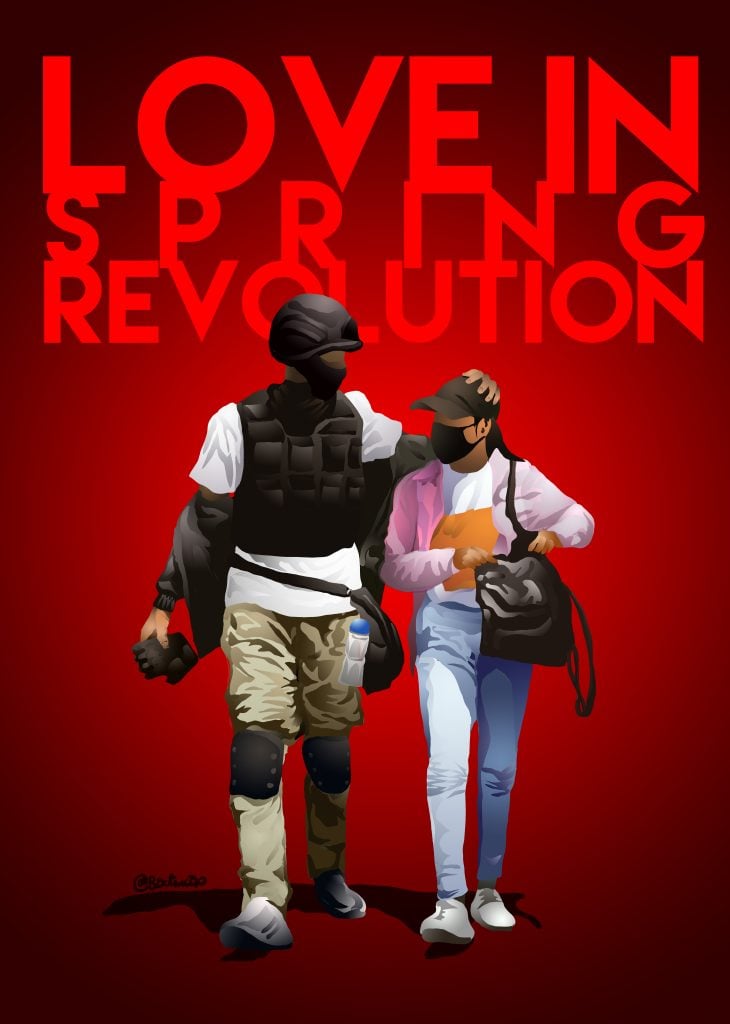

Badiucao, Love Always Wins (2021). Image ©Badiucao.

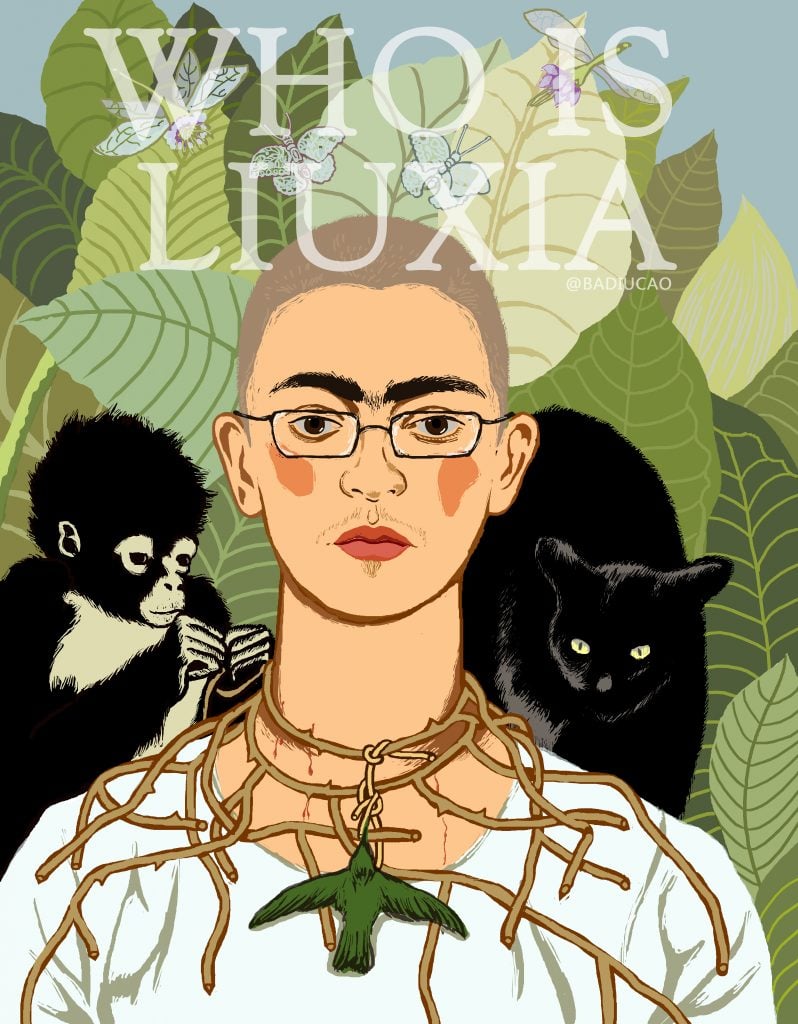

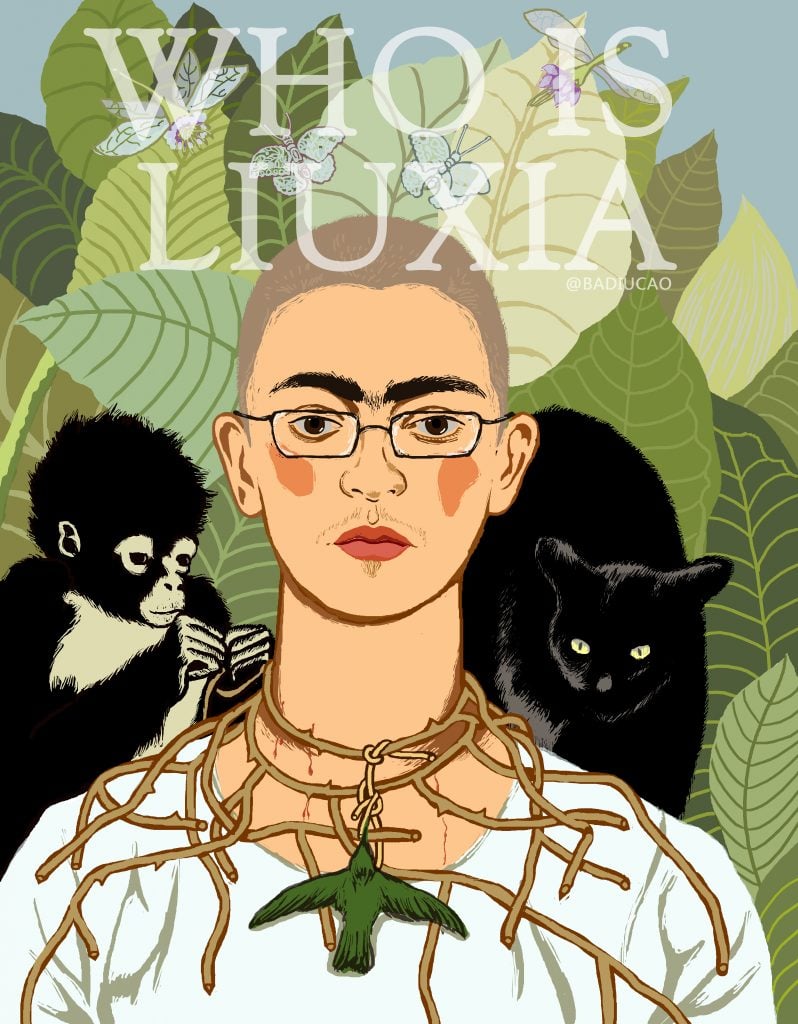

Badiucao, Who Is Liu Xia/Frida (2018). Image ©Badiucao.

Badiucao, Ideas Are Bulletproof (2021). Image ©Badiucao.

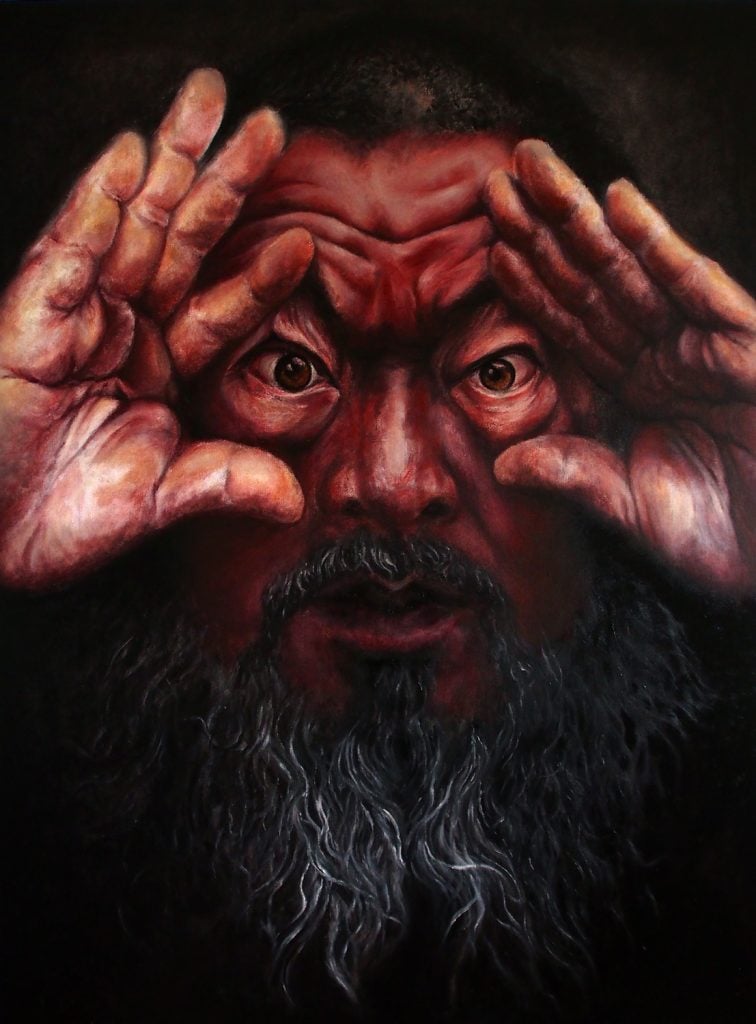

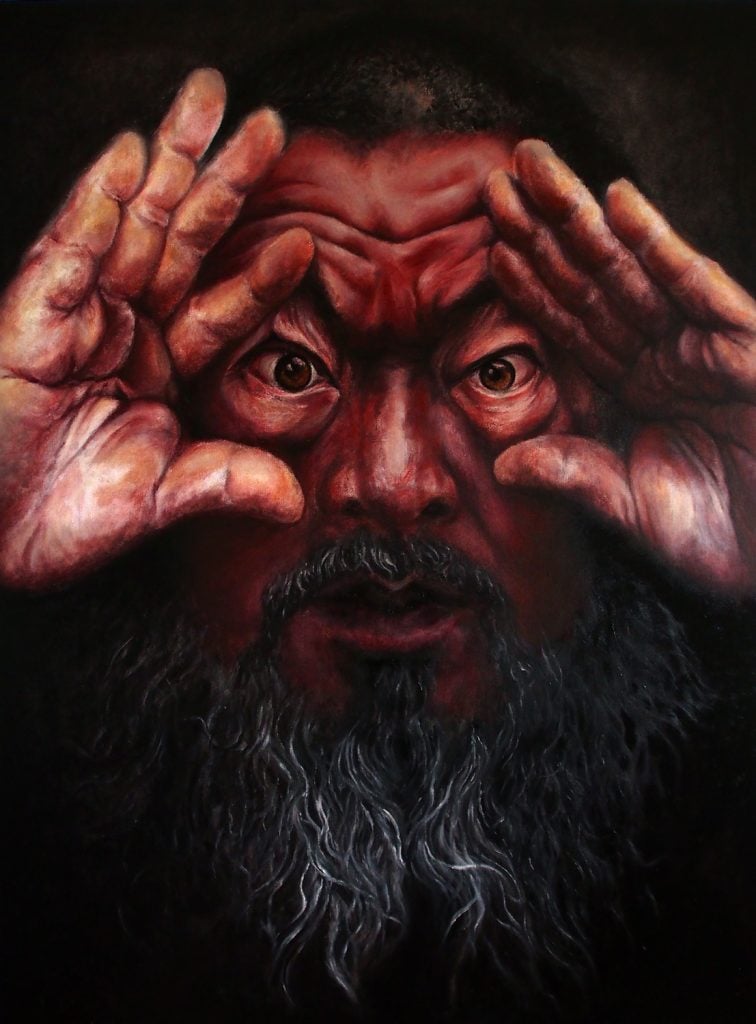

Badiucao, Ai (2015). Image ©Badiucao.

Badiucao, Milk Tea Alliance (2021). Image ©Badiucao.

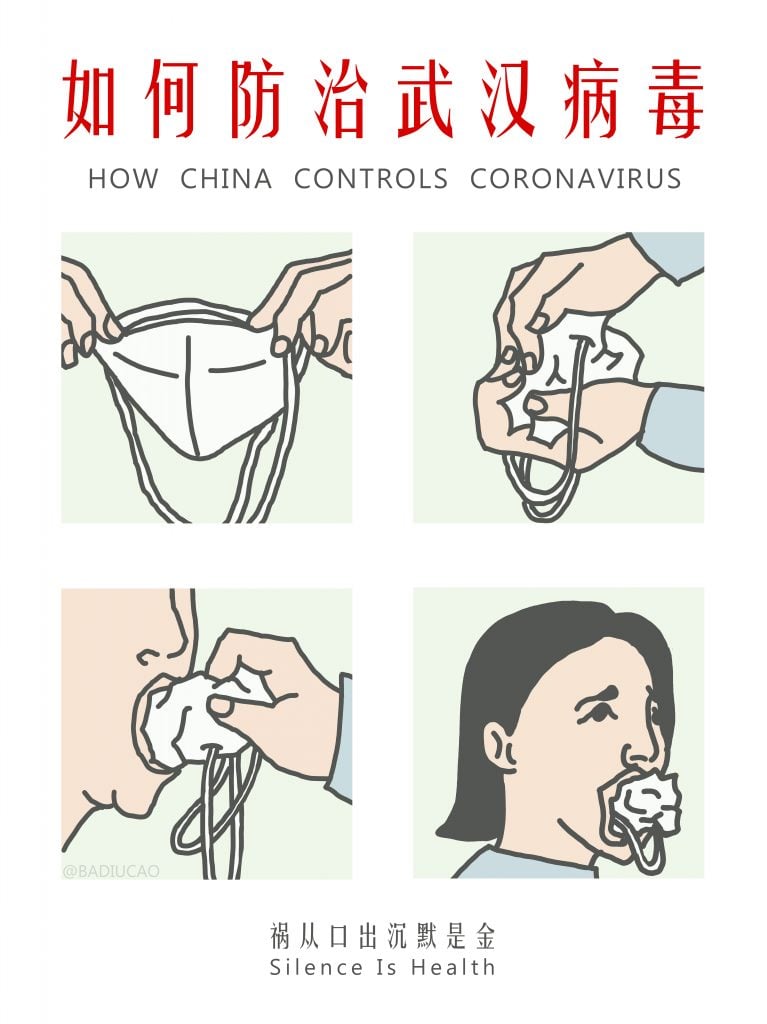

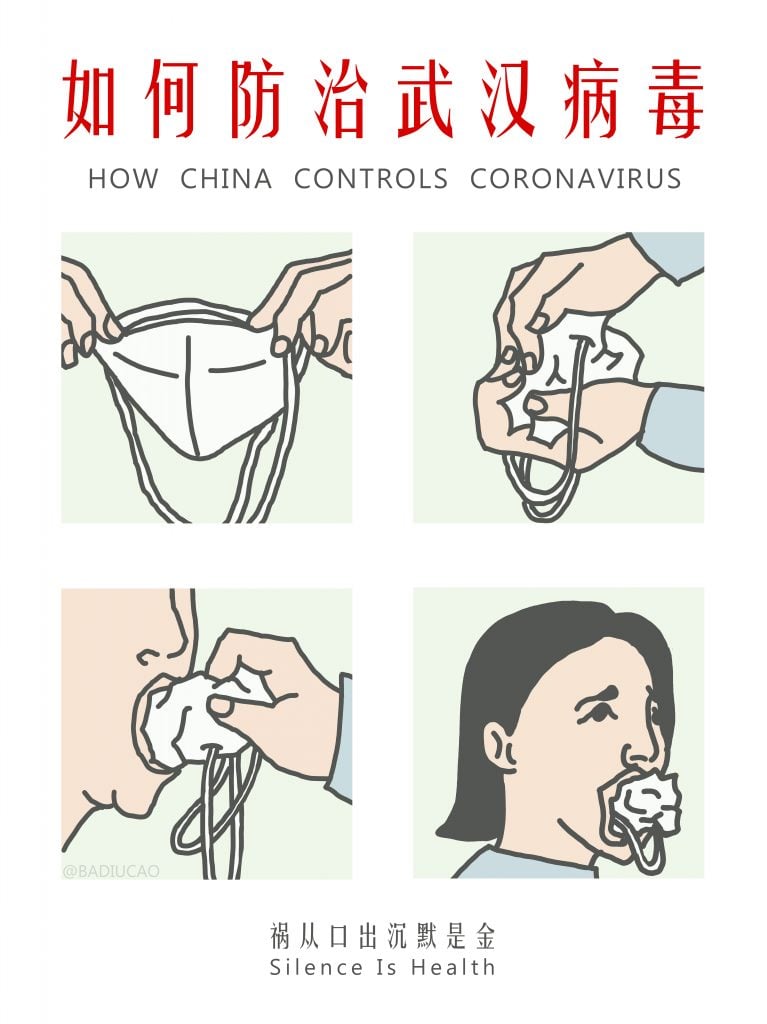

Badiucao, Medical Prints (2020). Image ©Badiucao.

Badiucao, No I Can’t, No I Don’t Understand, Covid Portraits for Dr. Li, (2020). Image ©Badiucao.

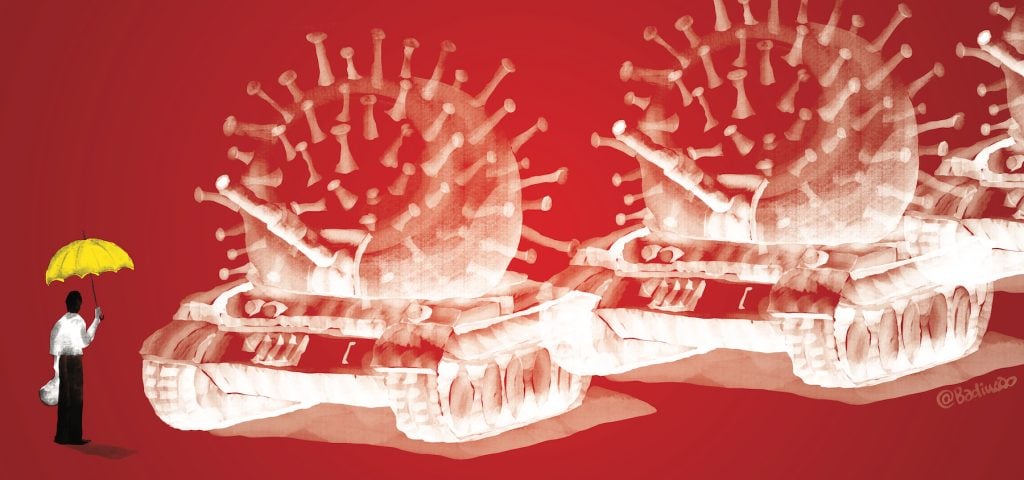

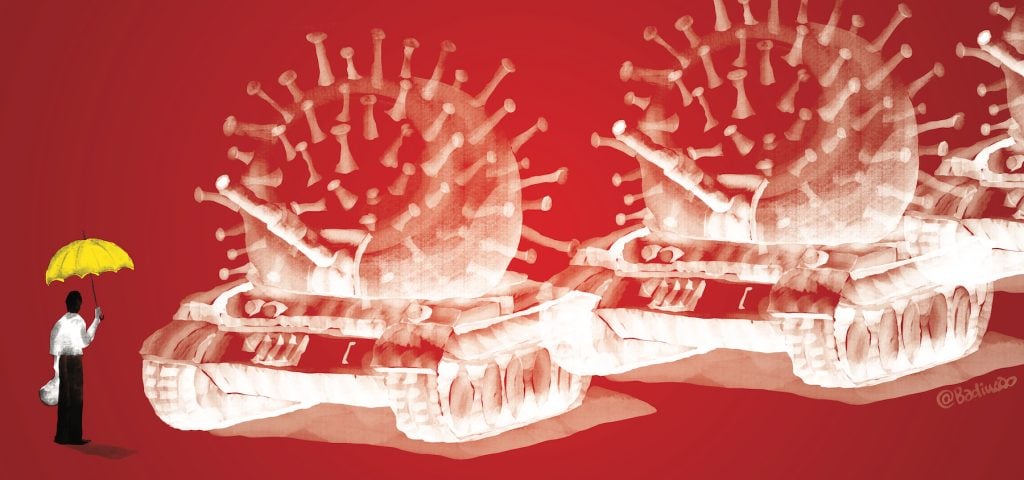

Work by Badiucao. Image ©Badiucao.

Work by Badiucao. Image ©Badiucao.

“China Is (Not) Nearby” is on view a Museo di Santa Giulia, Via dei Musei, 81, 25121 Brescia BS, Italy, November 13, 2021–February 13, 2022.