People

Why Is There Such a Hunger for Ivy Haldeman’s Paintings of Human-Like Hot Dogs and Hollow Suits?

Lately, the artist has had sold-out shows, five-turned-six figure sales, and interest from New York to Shanghai.

Lately, the artist has had sold-out shows, five-turned-six figure sales, and interest from New York to Shanghai.

Arden Fanning Andrews

The objects in Ivy Haldeman’s larger-than-life paintings have aspirations, too.

Disembodied figures of sharply shouldered blazers with matching pencil skirts appear as if they’ve strolled out of earshot after a board meeting to discuss how they really feel. Anthropomorphic hot dogs with dainty features lounge suggestively, read, apply moisturizer, and talk on banana telephones inside their golden buns.

“I find them very relatable,” said Haldeman on a call from her Brooklyn Navy Yard studio in New York. The artist, 36, has been painting quirky, quotidian moments of animated, inanimate things for half a decade, though her work feels increasingly relevant after a couple of years spent indoors.

The human gestures of her slightly bored hot dogs and empty power suits simultaneously convey lethargy, longing, and luxury, meanwhile grappling with issues of gender and identity in ways that now place Haldeman among the most in-demand artists of her generation.

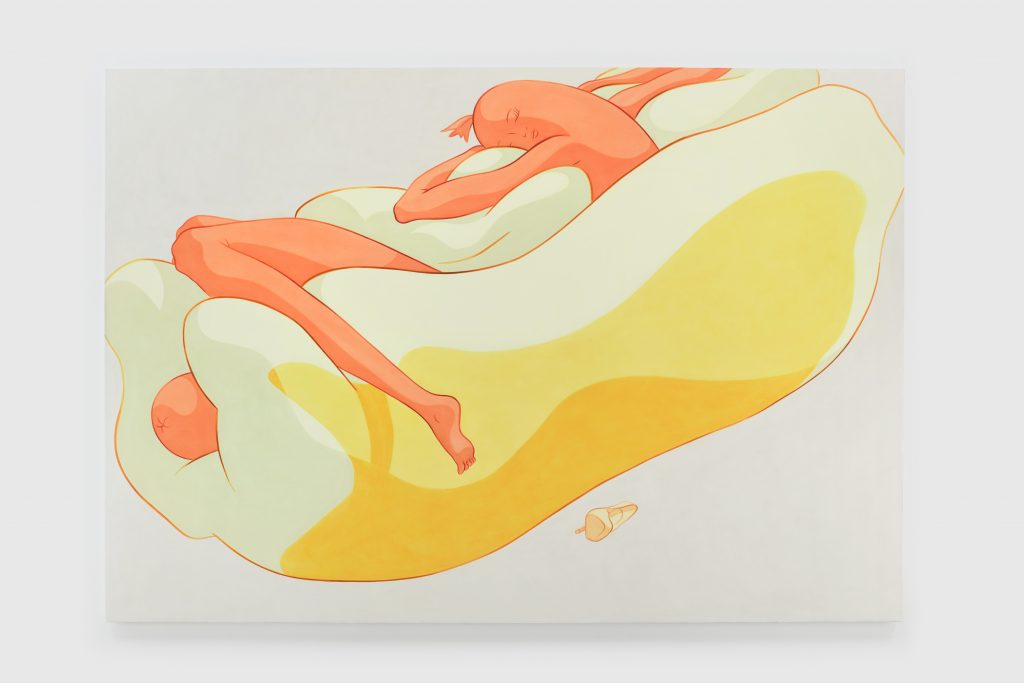

Ivy Haldeman, Two Figures, Eyes Closed, Arm Outstretched, Leg Dangles, Forearms Cross, Toe Touches Edge, 2021. Collection of the Yuz Foundation. Photo: Pierre Le Hors; courtesy of the artist and Downs & Ross, New York.

“Ivy focuses a kind of spell-bound attention towards visual codes of aspiration and autonomy,” said gallerist Alex Ross. He is the director of Downs & Ross, which represents Haldeman in New York. “It’s hard to think of a practice that more subtly marbles relations between desire and consumerism in ways at once this alluring and sleekly complex.”

He added, “All of her recent solo exhibitions, globally and without exception, have sold out.”

Prices have risen with demand. In the last year, for example, Haldeman’s acrylic on canvas Two Suits, Wrist Bent, Cuff to Pocket (Mauve, Peach), part of her 2019 Capsule Shanghai exhibition “(Hesitate),” had been estimated to sell for $20,000–$30,000 at auction. Instead, it pulled in over $138,000.

Ivy Haldeman, Two Suits, Wrist Bent, Cuff to Pocket (Mauve, Peach), 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Capsule, Shanghai.

Today, Haldeman’s artworks are held in public and private collections internationally—from the Dallas Museum of Art to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami to Beijing’s X Museum and the Yuz Museum in Shanghai.

While planning Haldeman’s first solo show at Downs & Ross in September 2018, Ross said, “It was self-evident that she was advancing a new language for portraiture that would prove to be extremely significant.”

Haldeman’s paintings speak an idiosyncratic yet universal language. Inspired by the way color reads on the Ukiyo-e woodblock prints of Japanese artists such as Kitagawa Utamaro, she uses pigments to create a backlit effect, as if you are seeing her works through a screen.

When painting, she allows thin layers of acrylic to dry for 24 hours at a time, to help her canvases reflect light. “I think about the materials of my work a lot,” she said. “Acrylic is a type of plastic, and it’s very funny because my grandfather was a plastic salesman,” Haldeman said. “The plastics company paid for my mother’s education in art. Now, I’m here [creating] paintings made out of plastic.”

A view of the 2021 exhibition “Ivy Haldeman: Twice” at Downs & Ross, New York. Photo: Phoebe D’Heurle; courtesy of the artist and the gallery.

The artist has long been reflecting on the visual culture of capitalism. “When I was five years old, I was thinking about suits,” she said. “I was like, How is one a grown-up? How does one usurp power in the world? This imagery comes into the psyche very early.”

By that time she had already received her first sketchbook, a gift from her textile-artist mother, who would take the Colorado-born Haldeman to museums wherever their military family moved—Boston, Maryland, Germany, and beyond. “I have memories of falling asleep on her big printing tables where she would be painting silk scarves,” she said. “She really encouraged me to engage with art.”

Haldeman went on to study at New York’s Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. “I didn’t actually know if I wanted to do art, but I felt like I needed to expand my world,” she said. After graduating, still unsure, she took legal and medical copywriting jobs and trained as an EMT.

Then, she said, “I had this funny moment where I was like, You know what I love to do? I love to daydream about all the things that I could be.” And so she chose the life of an artist.

While Haldeman started sketching her hot dogs after a 2011 trip to Buenos Aires, inspired by a hand-painted snack advertisement that she spotted on the side of a corner store in the city, her experience of living—or surviving—in New York City as a young artist lent the initial drawings new meaning.

“A really important part of me coming to paint this hot dog figure was realizing that the hot dog wasn’t a figure to laugh at,” she said.

Ivy Haldeman, Full Figure, Head Leans on Bun Edge, Leg Akimbo, Bottom Enfolded, 2021. Photo: Phoebe D’Heurle; courtesy of the artist and Downs & Ross, New York.

“I know what it’s like to try to be a person, but you find that you’re just caught in the grind of work and commercialism. I know what it’s like to feel very masculine, but not know what to do with my femininity. I know what it’s like to be a rough-and-tumble human, but aspire to some kind of upper-class elegance.” Her hot dog buns are sometimes fashioned as fur coats.

Long fascinated by Hellenistic works, Haldeman has always imagined her hot dogs as colossal figures. Over time, both her studio space and her works have expanded to fit this dream; she now employs two assistants in her Brooklyn Navy Yard studio, whose 14-foot ceilings and 10-foot doors make transporting her increasingly large-scale canvases feasible.

This summer, Shanghai’s Yuz Foundation is set to host a solo show from Haldeman featuring her largest paintings yet, measuring up to 20 feet in length.

Lily Wang, the foundation’s associate director, compared Haldeman’s work to sculptor Claes Oldenburg’s Two Cheeseburgers, with Everything (Dual Hamburgers) and also to French literary theorist Roland Barthes’ Mythologies. “People can easily see themselves in her paintings,” she said.

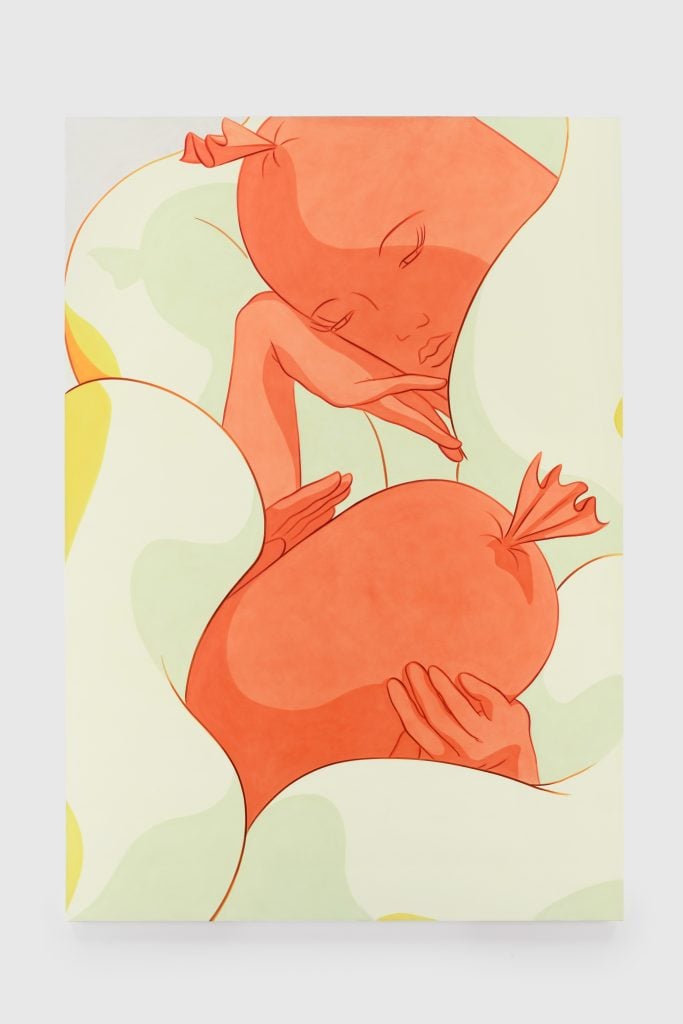

Ivy Haldeman, Twice Colossus, Head Leans Left, Pinky Up, Head Leans Right (Gaze), 2021. Collection of the Smart Museum, The University of Chicago. Photo: Phoebe D’Heurle; courtesy of the artist and Downs & Ross, New York.

Haldeman’s most recent works grapple with the constant encounters one has with one’s own image nowadays, when the intent may be “to project into other social spaces, but you are in fact looking at yourself while you’re doing it,” she said. It’s a relatable pursuit for everyone navigating a progressively digital, secluded world that simultaneously invites constant visibility.

Last year, an anonymous donor purchased Haldeman’s Twice Colossus, Head Leans Left, Pinky Up, Head Leans Right (Gaze) for the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art. It features two hot dogs gazing at each other—or, perhaps, one hot dog staring at its own reflection.

Either way, as Jennifer Carty, the associate curator of modern and contemporary art, said, “During our incredibly unpredictable and tumultuous times, it feels right to turn to the surreal.”

The real world is indeed exhausting, filled with all-too-real power trips and interactions, both online and IRL, that feel less human than hot dogs and hollow suits. Haldeman’s work offers a sense of respite from it all, residing in a “fantasy space where nothing is happening,” as she said.

“It takes on a new meaning when everyone is at home, perhaps luxuriating on a couch that looks remarkably like this bun.”