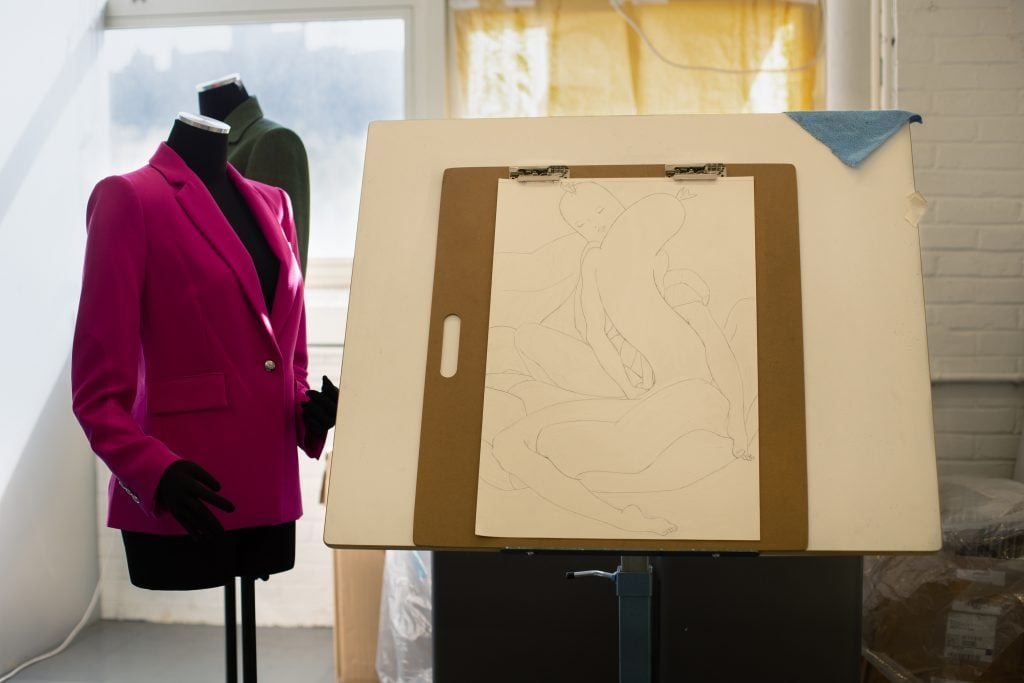

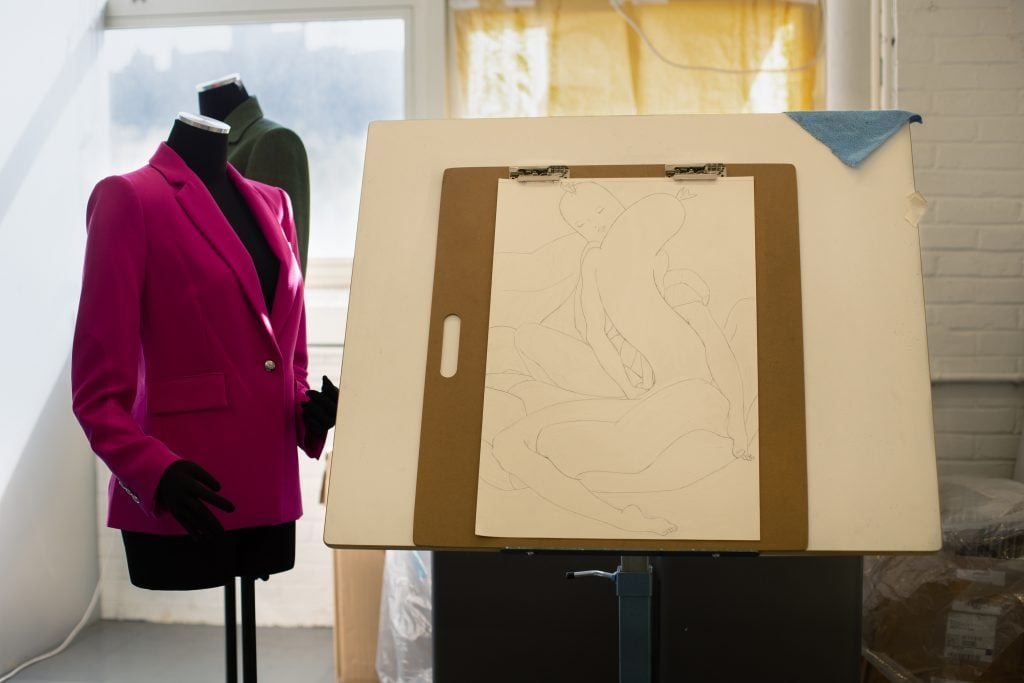

One will find a number of curiosities inside Ivy Haldeman’s Brooklyn Navy Yard studio: fake On Kawara paintings, mannequins sporting dramatically shoulder-padded blazers, a small citrus garden on a windowsill. The artist, who is best known for her larger-than-life paintings of hot dogs in repose, however, does not keep this processed meat on hand in the studio.

This conspicuous absence begins to make sense when one realizes the atmospheric rigor Haldeman strives to maintain in her studio—atmospheric in the literal sense. Her studio is filled with gauges measuring the humidity and temperatures of her studio space. Small variations, she’s noticed, make quite a difference in her compositions.

Courtesy of Ivy Haldeman. Photograph by Joe McShea.

Haldeman moved into the studio a few years ago after carefully searching for a recipe of perfect elements: good light, a freight elevator, top-notch ventilation, space to stretch and prepare canvases. Oh, and the studio needed to be a not-so-impossible distance from Chinatown noodles.

Right now Haldeman and her team are preparing for her upcoming solo exhibition at Los Angeles’s François Ghebaly in September, working on the process of bringing drawings to life on canvas. We caught up with the artist to talk about her highly specific listening choices and the studio task on her agenda that she’s most looking forward to.

Tell us about your studio. Where is it, how did you find it, what kind of space is it?

I work in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, in a multistory manufacturing building. There are a lot of fabricators here, small import/export businesses, a few other artists. The sets for Saturday Night Live are made on the ground floor. This building was probably constructed for military purposes, and is now, ironically or not, used for cultural production. I actually sublet my space from a larger fabricator who’s had his business in the building for over 20 years.

What made you choose this particular studio over others?

I need very particular elements in a studio. Good, bright lighting. It’s good to have daylight in addition to electrical lighting. I like to be able to see the paintings in different lighting conditions. I need a space that I can divide into different work areas, as many different types of processes are needed to make the paintings—some messy, some very clean, and they need to be separate. It needs to have the ability to be ventilated, as well as have neighbors that don’t produce noxious fumes. I need a sizable freight elevator, so as not to kill the art handlers, and temperature control, for the materials and for the people. It needs to be a reasonable commute for the people who work with me. I looked at a lot of studios during the pandemic—I had my pick through Manhattan and Brooklyn when the city emptied out—but this was the one studio that met these conditions at a reasonable price.

Courtesy of Ivy Haldeman. Photograph by Joe McShea.

Do you have studio assistants or other team members working with you? What do they do?

I do have a few people working with me. It’s important for me to have a very stable and archival surface to work on. To ensure this, we make all the surfaces ourselves. There is a lot of labor that goes into stretching, sizing, and preparing canvases. We are always testing and monitoring materials, and keeping records of our processes. Also, the painting surface needs to have a particular luminosity and texture, which takes a lot of gesso and sanding. There is the general upkeep of the studio, which needs regular organizing and cleaning. The painting process takes a number of steps, from drawing, material tests, and color tests. I have my team doing whatever doesn’t require my particular hand and sensibility. I do love having people work with me, it brings different skills and knowledge sets into the practice.

What is the first thing you do when you walk into your studio (after turning on the lights)?

Wash my hands and open the blinds to let in the natural light.

Courtesy of Ivy Haldeman. Photograph by Joe McShea.

What is a studio task on your agenda this week that you are most looking forward to?

Painting a mauve suit.

What are you working on right now?

I am preparing for an exhibition at François Ghebaly’s L.A. space in the fall. I am currently in the various stages of sketching with watercolors, creating pencil drawings, and bringing these images to the canvas.

What tool or art supply do you enjoy working with the most, and why? Please send us a snap of it.

I am very attached to my temperature and humidity gauges. I have about four or five of them lying around the studio in different areas. I think it comes from working in so many old commercial buildings in New York City, and realizing that all the quirks these buildings have—humidity from cement floors, heat from southern windows, the painful dryness of heating pipes, etc.—will affect how your materials and people function in a space. There are so many things that are subjective in an art practice, but these gauges help me monitor if I’ve generally gone mad, or am just delirious from the cold or heat.

Courtesy of Ivy Haldeman. Photograph by Joe McShea.

What kind of atmosphere do you prefer when you work? Is there anything you like to listen to/watch/read/look at while in the studio for inspiration or as ambient culture?

My current schtick is an eight-hour, no-loop 4K recording of deep forest birdsong. But I also like a good Marxist text; nothing gets me in the mood for art-making like David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years.

How do you know when an artwork you are working on is clicking? How do you know when an artwork you are working on is a dud?

I’m usually looking for some empathetic pang. I generally believe that people will get a feeling from a painting before they really see it. If an image I am making feels smart or tricky or just boring, I know I’ve strayed the path.

When you feel stuck while preparing for a show, what do you do to get unstuck?

I usually need a break. There’s nothing like some cheap Chinatown noodles with friends.

Courtesy of Ivy Haldeman. Photograph by Joe McShea.

What images or objects do you look at while you work? Do you have any other artist’s work in your studio?

I have a few mannequins wearing business suits in the studio. I use them for reference in drawings, and generally just appreciate their company. As for other artists’ work, I have a fake On Kawara that I keep around. There was a time when I would make On Kawara paintings as birthday gifts for friends. This one’s just made with a cheap stretcher and house paint, but I appreciate being reminded of Kawara’s practice: the daily task, the simplicity, the capturing of time. I think there is something there that I aspire to.

What’s the last museum exhibition or gallery show you saw that really affected you and why?

I keep thinking about the Kehinde Wiley show at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. The show is so carefully orchestrated, and yet there is a lot of repetition that lays bare the formulas he uses to make the body of work. There is a certain removal of the artist from the artworks, but I feel his intention goes so far beyond the objects in the gallery, and his actual materials are the social narratives and structures that he empowered himself to navigate. His practice brings up a lot of questions about the role of the artist, their relationship to their object making, and how one should use their platform in the world.

Courtesy of Ivy Haldeman. Photograph by Joe McShea.

Is there anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising?

I have a little garden along my windowsill. It’s full of citrus plants that I have grown from seed, including yuzu trees, sweet lemons, and Makrut limes.

What is the fanciest item in your studio? The most humble?

The fanciest: Artfix Primed Polyester Canvas, conservator-approved, avowedly prepared in the temperate caves of France. The most humble: the tool that takes on the auxiliary labor of mixing paints and cleaning the bottom of containers, the 20-year-old beater of a paintbrush.

What’s the last thing you do before you leave the studio at the end of the day (besides turning off the lights)?

I usually have some time just staring at and pacing around my paintings.

What do you like to do right after that?

Turn off the studio lights, carry my bike downstairs, and ride off into the night.