Labor Day means there’s just one month left in the Major League Baseball (MLB) regular season. This year, the holiday also mark the opening of New York City’s new Jackie Robinson Museum, dedicated to the historic player who broke baseball’s racial barrier—14 years after it was first planned.

Robinson was not only as a legendary baseball player, but someone who fought for equality throughout his life. Before joining the MLB, he served in an Army battalion of all-Black soldiers during World War II. According to military historians, Robinson refused orders to sit at the back of an Army bus and was court-martialed, but later acquitted.

In 1947, he became the first Black modern player to break the league’s 63-year-long segregation streak. According to the official MLB website, Robinson played 1,382 career games, scoring 947 runs for the Brooklyn Dodgers—137 of which were home runs.

Yawkey Sports Gallery at the Jackie Robinson Museum. All photos courtesy of the Jackie Robinson Foundation.

The team, now based in Los Angeles, crossed the country to honor Robinson with a visit to the new museum in Tribeca this past week, ahead of its public opening on September 5..

After making it to the big leagues, Robinson leveraged his fame to champion Civil Rights in New York, co-founding the Freedom National Bank in Harlem, which provided banking services for Black residents in 1964. He also created the Jackie Robinson Development Corporation in 1970 “to build affordable housing for Black citizens who were discriminated against in the housing market,” said Ivo Philbert, the vice president of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, speaking to Artnet News.

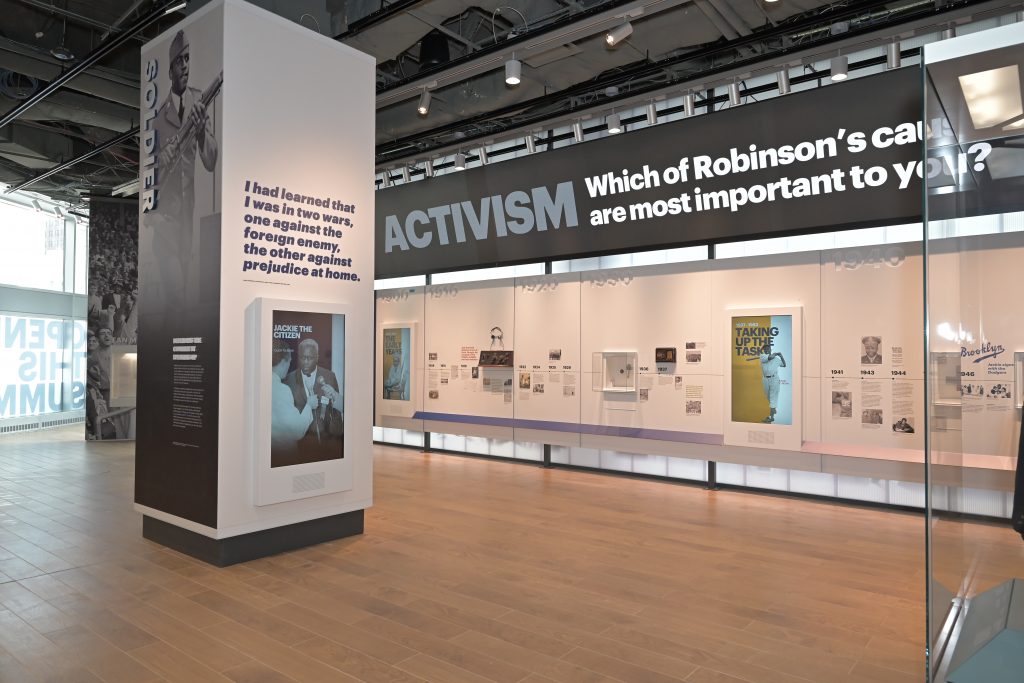

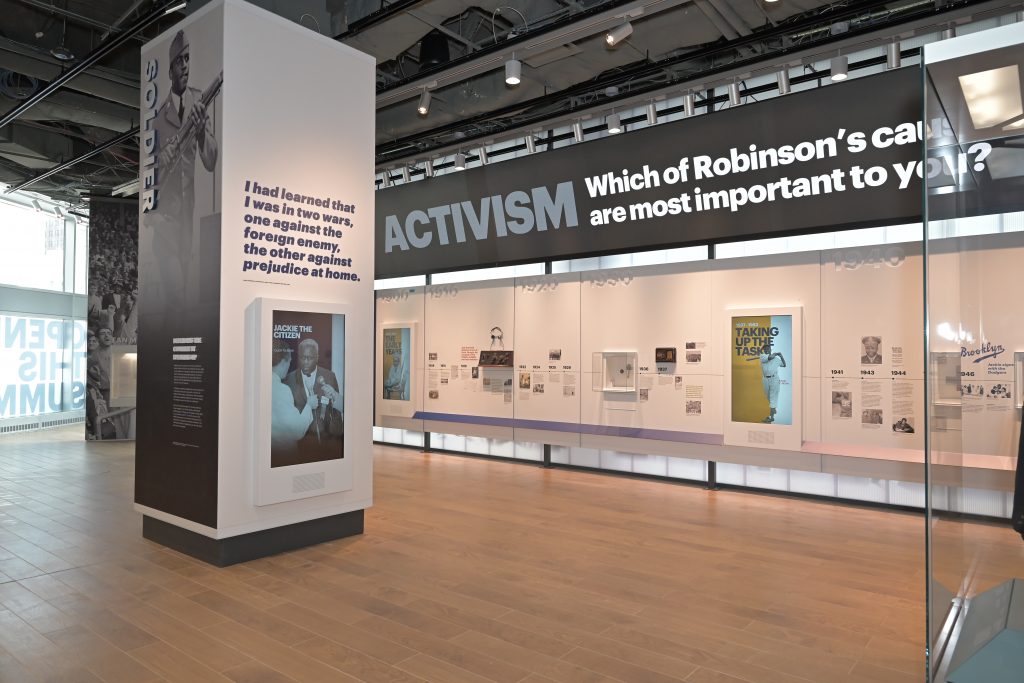

The Jackie Robinson Museum, which the New York Times reported is the city’s “first museum dedicated largely to the civil rights movement,” tells his story through 4,500 artifacts. Most come from the personal collection of his wife, Rachel Robinson, as well as from other private collectors and institutions like the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, and the Library of Congress, in Washington, D.C. The displays on view include comic books, contracts, and even a 3D model of Ebbets Field, where Robinson earned so many of his accolades.

Main Gallery at the Jackie Robinson Museum.

Despite Robinson’s popularity and history-changing efforts, it took more than a decade to make his family’s dreams of establishing a museum dedicated to his life a reality. “Rachel Robinson had long ago expressed an interest in a fixed tribute to her husband that would tell the full story of his multifaceted life,” Philbert told Artnet News. “Mrs. Robinson also wanted the public to learn of his deep commitment to advancing Civil Rights and equal opportunity to ensure first class citizenship for all members of society.”

The Foundation sought $42 million to construct the museum, Philbert said, but two global financial crises, Hurricane Sandy, and the pandemic each created their own obstacles, from building permits to supply chain holdups. “We weathered those hurdles and soldiered on during those challenges and were fortunate to attract funding from a host of generous donors,” Philbert said. According to the Times, the foundation raised $38 million in the end.

At age 100, Rachel Robinson cut the ribbon on the museum’s new home at a soft opening party earlier this summer. She had pushed for the institution to be location in Manhattan, Philbert said, to attract maximum attendance. “Additionally, one of the foundation board members, Len Coleman, had an affiliation with Trinity Church,” which owns the building in which the museum is now housed, in a joint venture with Norges Bank. This “allowed for an attractive and long-term leasing opportunity,” Philbert said.

Another view of the Main Gallery at the Museum.

And while the museum has finally reached its goal, this Monday’s opening is not the end of the story, since the institution views Robinson’s legacy carrying into the present.

“When you think of the many challenges that Robinson’s generation experienced as far back as 1947—access to education, housing, voting rights, economic opportunity, social justice, and equitable treatment generally—those same challenges plague us today,” Philbert said. “While we have to acknowledge progress in these areas, for those subject to such disparity, fairness feels long overdue.”

Like art, sports have the power to bridge divides, and among the displays that will continue such conversations about equality, according to the Times, is an electronic marquee that “will offer a question of the day for visitors and school groups to generate conversations about race.”

“We believe that sports is a great equalizer, as the metrics of performance are fairly objective,” Philbert said. “With team sports, sharing a common goal leads to camaraderie and familiarity among players that often break down barriers in interpersonal relations.”

“We hope the Jackie Robinson Museum will inspire its visitors to work to improve their communities in positive ways,” Philbert added, “witnessed by the profound difference that one life made.”