Art & Exhibitions

Hieronymus Bosch Meets Madonna’s Daughter in Jacolby Satterwhite’s Epically Trippy New Video at Gavin Brown

It's the artist's first New York solo show since 2013.

It's the artist's first New York solo show since 2013.

Sarah Cascone

“I’m so nervous,” admitted Jacolby Satterwhite. artnet News was visiting the artist at his Brooklyn apartment ahead of the opening of his upcoming show at New York’s Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, and he was feeling some jitters.

“My first solo show, no one knew who I was,” he added, noting that the pressure is way more “intense” this time around. Satterwhite’s first solo effort in the city was in 2013. “So much has happened for me since then, creatively, cerebrally, and critically. I hope of all of that comes through in what I’m showing.”

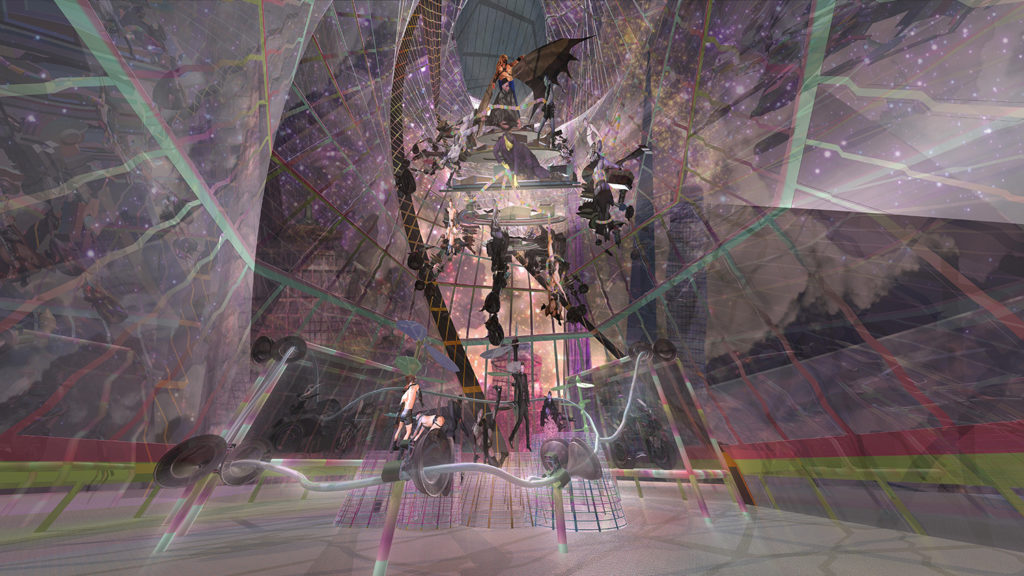

Titled Blessed Avenue, the exhibition is a concept album and an accompanying music video showcasing Satterwhite’s signature visuals, a trippy, queer fantasy of a dreamscape, with cameos from the likes of Raul De Nieves, Juliana Huxtable, and Lourdes Leon (Madonna’s daughter, now studying dance at a conservatory). At 30 minutes, it’s the artist’s longest animation to date—although Satterwhite is already teasing an extended director’s cut, on tap to be shown at Art Basel in Basel with Los Angeles’s Moran Moran.

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue, still image. Courtesy of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

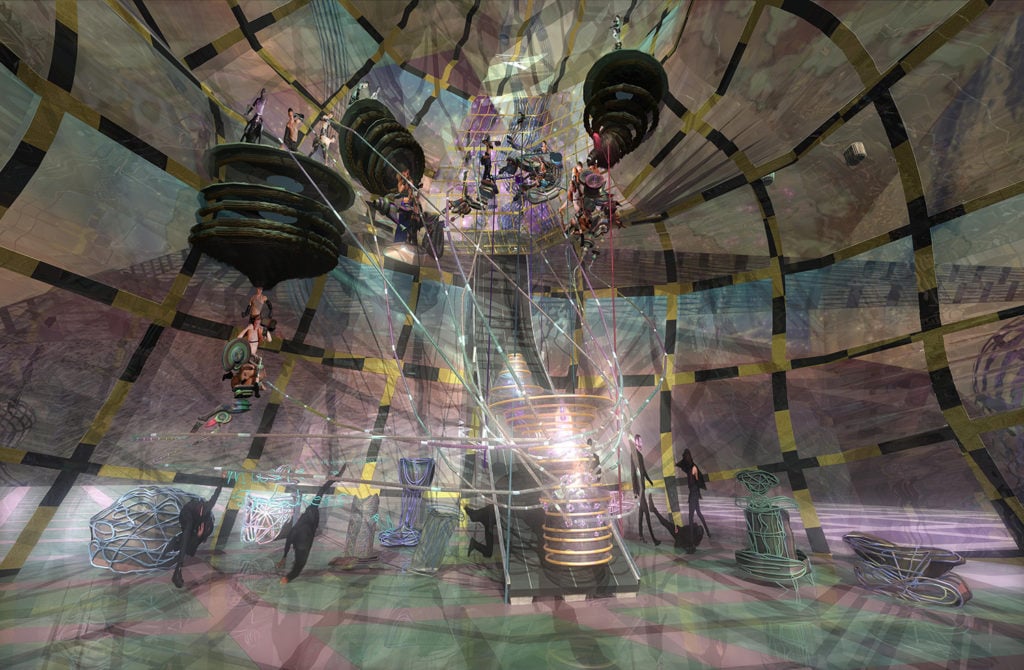

Blessed Avenue is also the artist’s most collaborative project to date. Satterwhite credits the many people with whom he has worked with giving him the confidence to consider his practice more broadly. “I started out as a very purist painter,” he said. “Exchanging creative energy with so many collaborators over this project gave me lots of courage, and freed me up to take on any genre or media and make it align with any concept.”

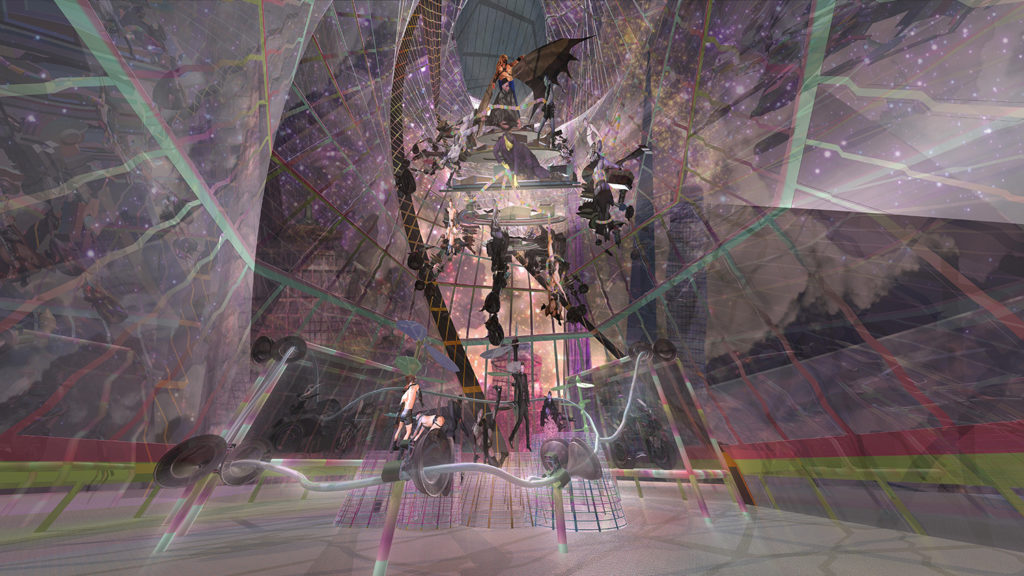

The entire exhibition is a tribute to the artist’s mother, Patricia Satterwhite, who died in 2016, leaving behind a trove of her own art and music. “It was a self-medication situation, a way of dealing with the crazy voices in her head,” Satterwhite explained. Using songs she recorded on cassette tape in the 1990s as a jumping off point, Satterwhite teamed up with Nick Weiss of Teengirl Fantasy to make a “disco, acid house, trip-hop record,” inspired in part by Daft Punk’s 2001 Discovery album, which had its own anime film.

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue, still image. Courtesy of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

The project began with a commission from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2014, which has been presented in part at various venues under the working title En Plein Aire. In some ways, however, Blessed Avenue’s roots go even deeper, back to 2008, when Satterwhite began thinking about working with his mother’s personal recordings.

“I had her drawings and cassette tapes in my archives, but I wasn’t sure what to do with them,” the artist recalled. “I took a Fluxus and Dadaist approach and would use them as a Surrealist prompt and just react. It was a secret way for me to loosen up whatever kind of creative jargon I was working on at the time.”

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue, still image. Courtesy of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

As a kid, Satterwhite remembers having friends over to play video games and being really embarrassed about how loudly his mother was singing in the other room. “A lot of the songs are about depression, her battle with schizophrenia, and love. They’re pretty standard tropes for pop music, actually,” he said. “I was like ‘Mom, they sound derivative!'”

Now, he appreciates the sophistication of what she was doing. Though these were simple compositions, performed a capella, they were rich with Southern influences from rhythm and blues, folk music, and Gospel songs. “What was really endearing about working with these tracks,” Satterwhite said, “was finding someone in the creative process who had absolutely no audience, but was still continuing to work.”

Before she died, Patricia was able to listen to the new versions of some of her songs. “She was really shocked,” Satterwhite recalled. “In the ’80s and ’90s, you’d have to be at Columbia Records with a studio to produce this kind of music. It was really alarming for her because she hadn’t left the house in 12 years, and [music-making] technology had come such a long way to be affordable for the average person.”

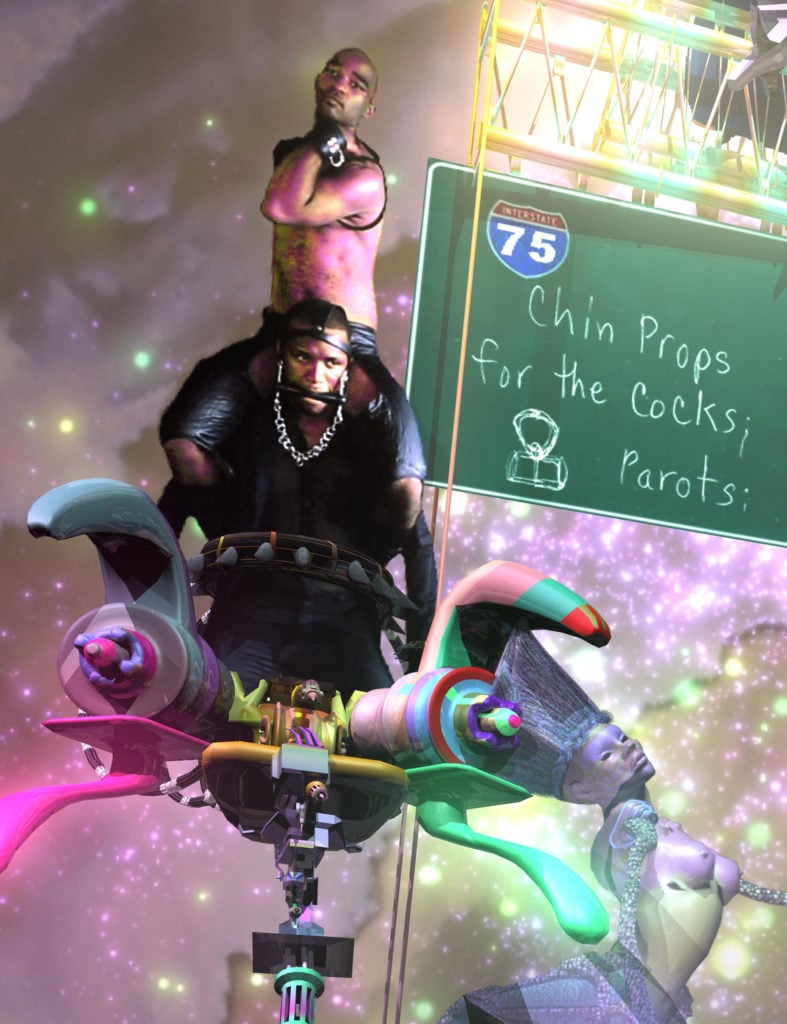

Patricia also comes through in the accompanying music video, which contains animated versions of her drawings, which Satterwhite has traced and turned into 3-D objects. In addition to populating the video landscape, her designs will also have a physical presence in the show.

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue, still image. Courtesy of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

“I thought it would be very meta if I realized my mother’s dream to have a QVC line,” Satterwhite said. So the artist teamed with stylist David Casavant—who also did the costuming for the video, with vintage pieces from the likes of Helmut Lang, Raf Simmons, and Alexander McQueen—to have affordable versions of his mother’s designs manufactured in China. “She made drawings of utilitarian objects like mugs, lamps, tables, and grills. That’s where there’s so many detailed, da Vinci-like instructions on them.”

They will be available for purchase at a display inside the exhibition and restocked regularly during its run. The shop component is a manifestation of Patricia’s dreams, but Satterwhite has his own personal goals for the show: “Museums are my number one priority. Being in a public collection means it lives forever in a really respected way, and it doesn’t collect dust.”

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue, still image. Courtesy of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

“The Renaissance is really where my head is. The Renaissance was all about conflations of many mediums, of music and dance and art,” Satterwhite explained. “In Blessed Avenue, the sonic portion is just as labored and custom and academic as the visuals portion, the dance portion, the relational aesthetics portion.”

“I’m trying to do a Garden of Earthly Delights thing,” he said, likening his work to that of Hieronymus Bosch and Piero dell Francesca, but “with a dark downtown aura.”

“It’s kind of set in these sadomasochistic factories,” Satterwhite added. “They look like BDSM films mixed with Japanime… it’s really explicit, but in a way that’s not gratuitous. There’s a lot of water torture.”

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue, still image. Courtesy of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

And what would Patricia have to say about all that?

“My mom would think it was funny, because she had a perverse sense of humor, and I would have felt uncomfortable with her finding it funny,” said Satterwhite. “This is kind of a send off for her. This is a way for me to move on and focus on the present.”

“Jacolby Satterwhite: Blessed Avenue” is on view at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, 291 Grand Street, March 10–May 6, 2018.