People

‘A Painting Is Never Finished’: Legendary Chef Jacques Pépin on His Secret Life as an Artist, and Why He’s Sharing It Now

The French American chef has a solo museum exhibition showcasing 50 years of his art.

The French American chef has a solo museum exhibition showcasing 50 years of his art.

Sarah Cascone

At age 86, Jacques Pépin is tired of writing cookbooks. That’s why his next book about chicken won’t be about how to cook it—instead, it will feature a selection of chicken-inspired artworks by the celebrated French chef, who happens to be just as at home behind an easel as he is at a gas range.

“I have over 130 illustrations painting chickens,” Pépin told Artnet News. “They wanted me to do recipes for it, but I said ‘I have 30 books of recipes. I don’t want to do more recipes!'”

The volume, due out this fall from Harper Collins, is more in the vein of his 2003 memoir The Apprentice, revisiting pivotal moments in Pépin’s life and career through the lens of preparing his favorite fowl, from collecting eggs as a child to serving as the personal chef for French President Charles de Gaulle. It will be titled Jacques Pépin, Art of the Chicken: A Master Chef’s Stories and Recipes of the Humble Bird.

“It will be a book of art and painting, but at the same time a book of stories,” Pépin said.

The book hasn’t been the only thing keeping the chef, who lives in Madison, Connecticut, busy. Since March 2020, Pépin has filmed more than 250 instructional cooking videos for his Facebook page, which is maintained by his daughter, Claudine Pépin. And then there’s his big exhibition at Connecticut’s Stamford Museum and Nature Center. Titled “The Artistry of Jacques Pépin,” it features more than 70 works of art created over the past 50 years.

Jacques Pépin, Interior Study (1974). Photo by Thomas Hopkins.

While Pépin dedicated himself to cooking from childhood, dropping out of school at 13 to pursue an apprenticeship, his passion for making art took time to bubble to the surface. When he moved to the U.S. in 1959, at 24, he made the unusual decision to return to school, beginning 12 years of courses at New York’s Columbia University. But very little of his education—which he completed at night, after working in the kitchen all day—involved the visual arts.

“One time I took a class in drawing and another one in sculpture, in the early ’60s. That was about it,” Pépin said. “But about that time, I had a bunch of friends who rented a house in Woodstock, New York. It was kind of an artist colony. We all started redoing furniture and painting and one thing or another. That’s probably where it started.”

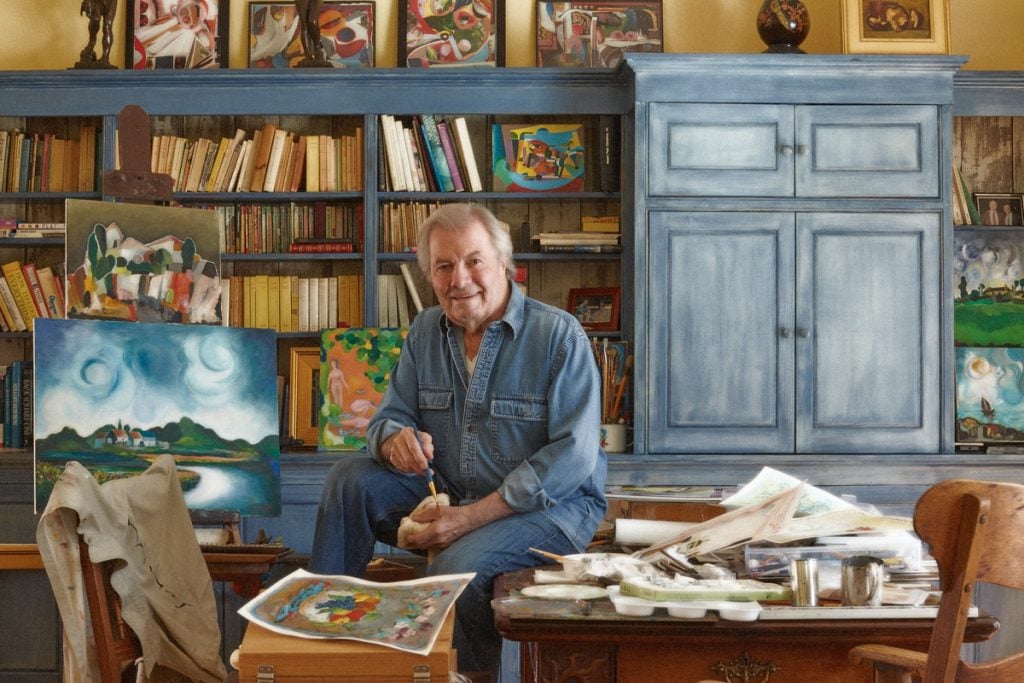

The works in Pépin’s museum show range from landscapes to abstract compositions. Many are illustrated menus for meals the chef created for family and friends during his 54-year marriage to Gloria Pépin, who died in December 2020 at age 83.

Jacques Pépin, La Boule des Dimanches (2010). Photo by Thomas Hopkins.

In 2015, Pépin began to sell his art online. Collectors can choose from original works on paper or canvas, which range from $4,000 to $30,000, as well as signed prints for $195 to $1,900. (A portion of sales support culinary education and sustainability.) “I didn’t want to do it, but it’s been more successful than I ever would have thought,” Pépin said.

We talked with the chef about the two sides of his creative life and how they fit together.

How did you come to illustrate so many menus?

When we would have guests at the house, I would write the menu out, and then I started illustrating them a little bit. I ended up doing a lot of chickens. Now we have about 12 books of those menus. That’s my whole life, basically. My daughter Claudine was here yesterday, and she was looking back at them and found one from when she was four years old where she had drawn a little chicken with its friend.

How does your approach to making food differ from your approach to making art?

I have been in the kitchen for over 70 years now, and I am known there for technique. Any good chef must first be a technician—repeat, repeat, repeat, so long that it becomes part of your DNA and you don’t have to think about it. In painting, it’s different, because I am not a great technician. I still don’t really understand all of the ways of mixing one paint with another to get different colors.

But otherwise, there is a similar process. As a professional chef, when I start cooking something, I don’t have a recipe. I take one ingredient, I put it with the other. It looks this way, so I do that. I test, I adjust. Eventually, the recipe kind of takes ahold of me and it takes me somewhere, and I stop when I think it’s finished.

Likewise when I start painting, maybe I know am going to do a landscape or a bunch of flowers, but I don’t know exactly where I am going. At some point, the painting kind of takes over, and then I react to it. I don’t even question myself. “Is it good, is it bad?” It’s immaterial to me. It’s just purely a kind of a reaction, just like the way that I do in cooking, in a sense.

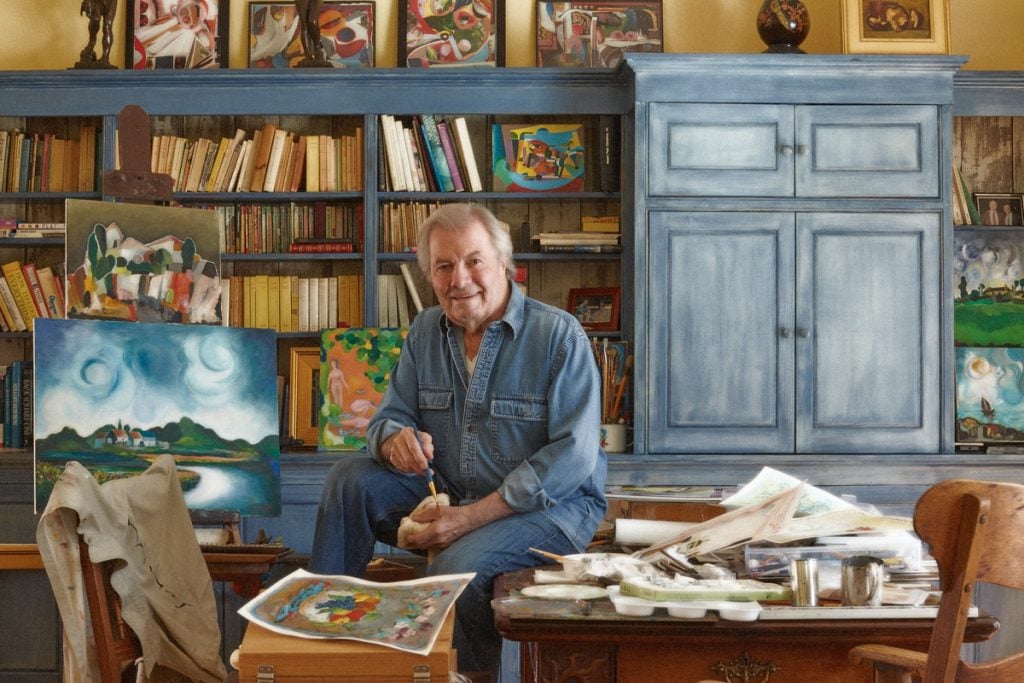

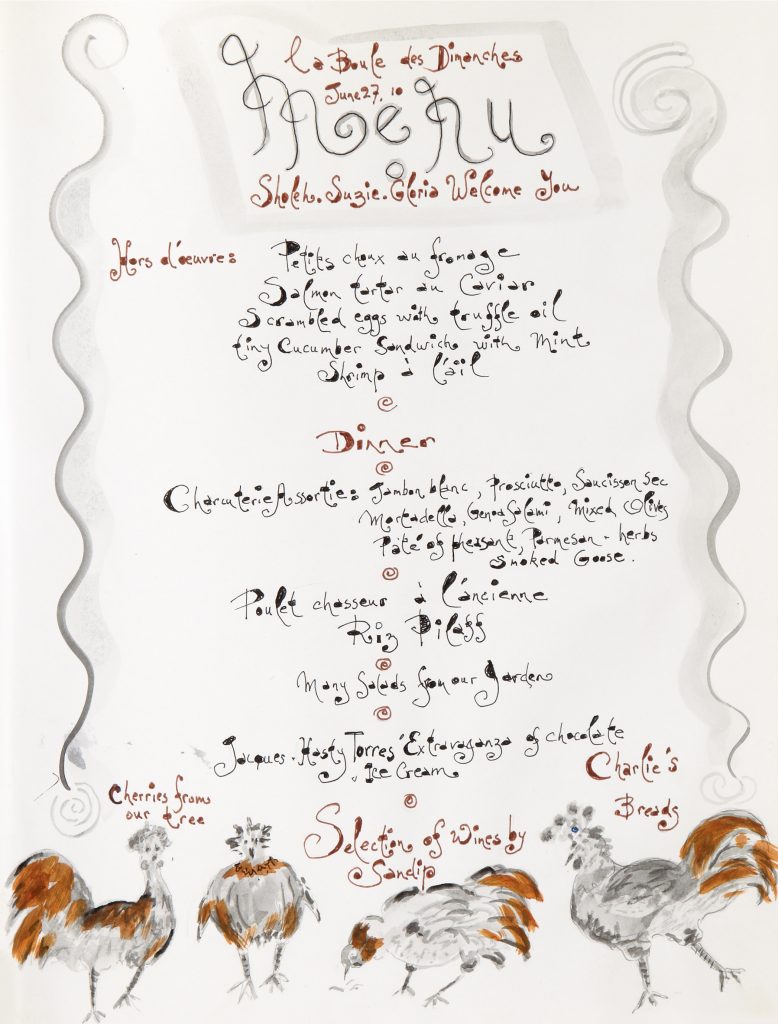

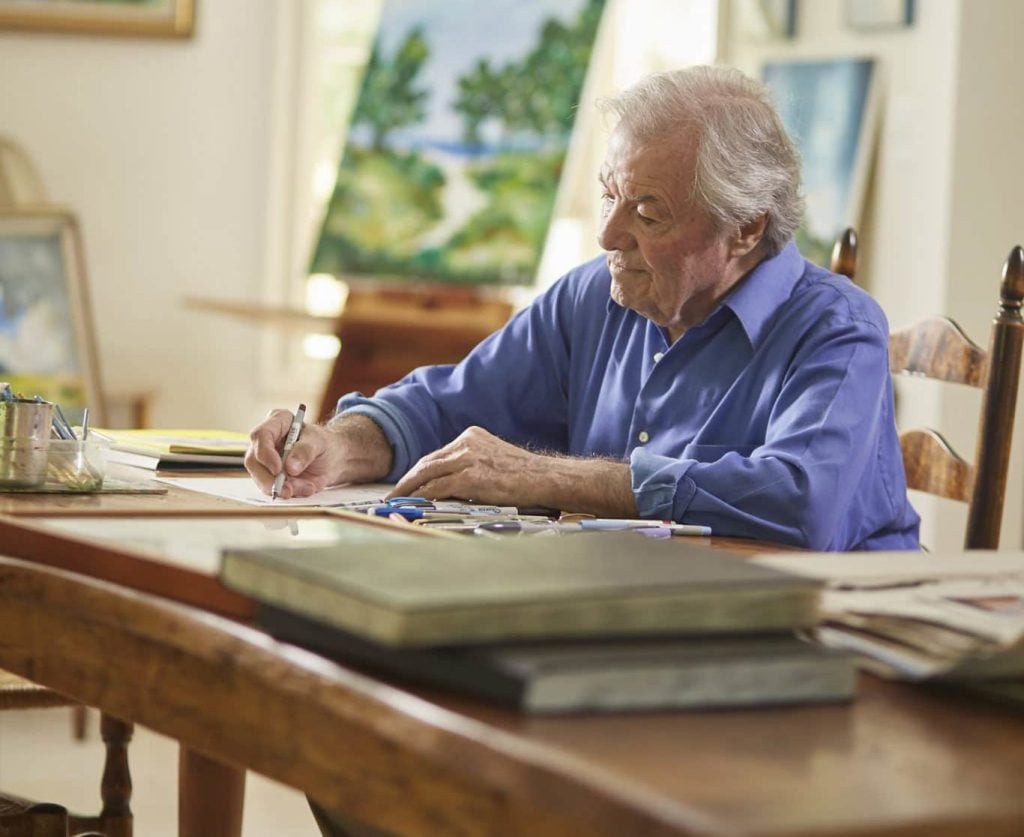

Jacques Pépin in his studio. Photo by Thomas Hopkins, courtesy of the Stamford Museum and Nature Center.

And how do you compare your finished results in the kitchen and in the studio?

Very often, I do a painting, and I retouch it and retouch it. It’s very hard sometimes to stop. In a sense, a painting is never finished, it’s just abandoned at some point. And if I see a painting a few years later, I will touch it again.

The food is different. I would love to be able to taste food that I made 50 or 60 years ago. I probably would be surprised to cook that way now. But of course the food is very vanishing. It disappears, and all you have left is memory.

Jacques Pépin, Patterned Blue Vase (2004). Photo by Thomas Hopkins.

Looking at cooking as an art form, how important is the visual component to making good food?

There is an aesthetic with food, but I have never emphasized the presentation, even when I was with Julia Child or other shows that I did on television. Of course I like food to look nice, but the most important part of food—the essence—is taste.

Is there any food item you don’t like to paint, that you don’t find appealing as an artist?

Not really! When I paint food, very often it’s very abstract or stylized. I don’t try to reproduce things exactly as they are. I look for a feeling, an emotion, for a structure in the canvas or an exploration of color more than anything else.

My daughter loves my abstract paintings. But they always end up with some kind of buffet table or some kind of picnic, something that is related to food to a certain extent even without realizing it. I guess I can’t escape myself.

Jacques Pépin, Vivid Buffet (2021). Photo by Thomas Hopkins.

What about a favorite ingredient to paint? Chicken, I suppose?

I would say chicken, but after that, certainly flowers. Flowers are the perfect transition between abstract and representational painting. I’ve also done a bit of the same thing with vegetables. I’ve done some chickens that look like an artichoke or leeks or different types of vegetables or fruits. There is always something that brings me back to food. But I paint it more the way I feel it than I see it.

In the art studio, do you like to drink a glass of wine while you work?

Wow, no one has ever asked me that question. The wine comes after, as a relief. When I am painting, it’s the same as when I am cooking. I get engrossed in it. I listen to music, but I don’t really think about food or wine until I am finished for the day. I like classical music, modern jazz, and old French songs from Édith Piaf and Yves Montand.

Jacques Pépin, Apple and Chicken (2020). Photo by Thomas Hopkins.

What was the most transferable skill from the kitchen to the art studio?

I’ve never really thought about that. You can use a knife or even a brush in the kitchen with pastry and certain other things. I guess I have a certain dexterity with a brush or a spatula that could apply to art.

I have always worked with my hands. When I was a kid, my mother had a little restaurant and she was a cook. My father was a cabinet maker. The choice was pretty easy: I was going to be a cabinet maker or a cook.

In my house here in Connecticut, I have four bathrooms in granite, in tile, in marble, and I did all of those myself. I made a mosaic with broken tiles. I have big stone walls outside that I made myself. I have some furniture on the porch, a table that I made myself.

If you were to have a dinner party with any artist from history who would you invite and what would you make?

Ay yi yi, I don’t know! Probably Picasso. He always fascinated me, the different periods that he had. I have been to his place in the south of France. And I would love to have Monet or Manet.

[For guests,] I usually try to cook not exactly what I like, but what they like. So I would try to do a little research on Picasso, being Spanish but living in the south of France. I would try to have some type of Mediterranean diet to please him. When you cook, there is a great deal of love. You cannot cook indifferently. You have to give a lot of yourself. Cooking is the purest act of love, whether its for your kid or your grandmother or your lover or your wife. It’s always to give.

Jacques Pépin, Tranquil Field (1999). Photo by Thomas Hopkins.

If cooking is the purest act of love, is painting a little bit more selfish or indulgent? Because you are giving that gift to the world, too.

You do, but painting is not as immediate or direct as cooking. I would cook a dinner for Picasso like I do for my friends—last night I had a friend, Reza Yavari eating here. He’s Iranian so I put more hot pepper in it than my palette can take usually, because I know he loves that. But when I paint, I never paint thinking about how to please someone else. I wouldn’t even know how to do that. I really paint for myself.

“The Artistry of Jacques Pépin” is on view at the Stamford Museum and Nature Center, 39 Scofieldtown Road, Stamford, Connecticut, November 19, 2021–January 30, 2022.