Art World

Outsider Artist James Castle Left a Treasure Trove of Works Hidden in the Walls of His House

Was this work intended as a time capsule?

Was this work intended as a time capsule?

Eileen Kinsella

When the city of Boise, Idaho, bought the home of renowned Outsider artist James Castle (1899–1977), it hoped to use the property to pay tribute to the homegrown artist’s life and work. As it turned out, the late artist had much more than a house to contribute to that mission.

After acquiring Castle’s property in 2015, the city began restoring the home in order to convert it into dual-use space: a public gallery to showcase the artist’s oeuvre and a studio residence for working artists. But the project yielded a far richer return than anyone could have imagined. Amid the restoration, art experts stumbled upon 11 previously unknown works concealed in the house’s walls.

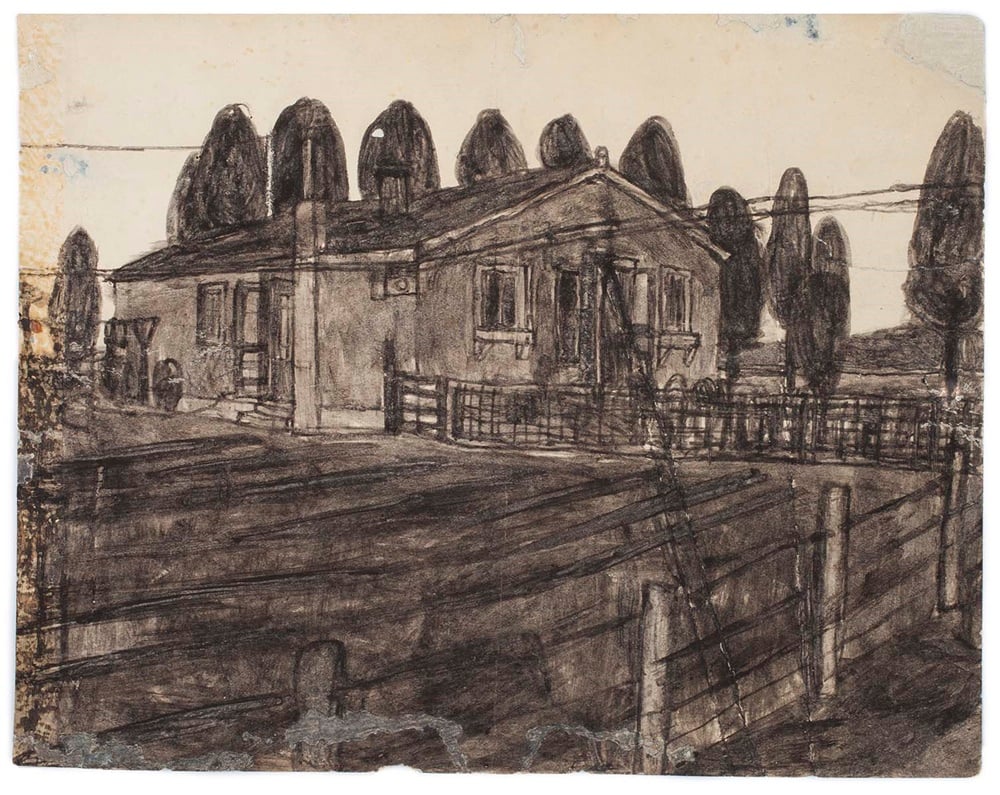

The exterior of the restored James Castle House. Image courtesy of the Boise City Department of Arts & History

Rachel Reichert, cultural sites manager for the Boise City Department of Arts and History, says that the newly discovered works were found when the restoration crew was searching for studs in the walls. Ten of the works were in the Castle family living room, and one was found a small book in one of the bedrooms, Reichert told artnet News. But they weren’t just lying around. “All were inside walls,” she says.

Castle was known for using found materials in his work. So Reichert and an architect began researching the site, looking for materials like sheetrock, wallpaper, and beaverboard that might help date different works. “We were discovering lots of different layers, so we just kept going,” she says. What they found was far more valuable than an artist’s raw material. Together with a gift of 50 works given by the James Castle Collection and Archive, the group of donated and salvaged works—61 in total—now have an appraised market value of about $1 million, according to Reichert.

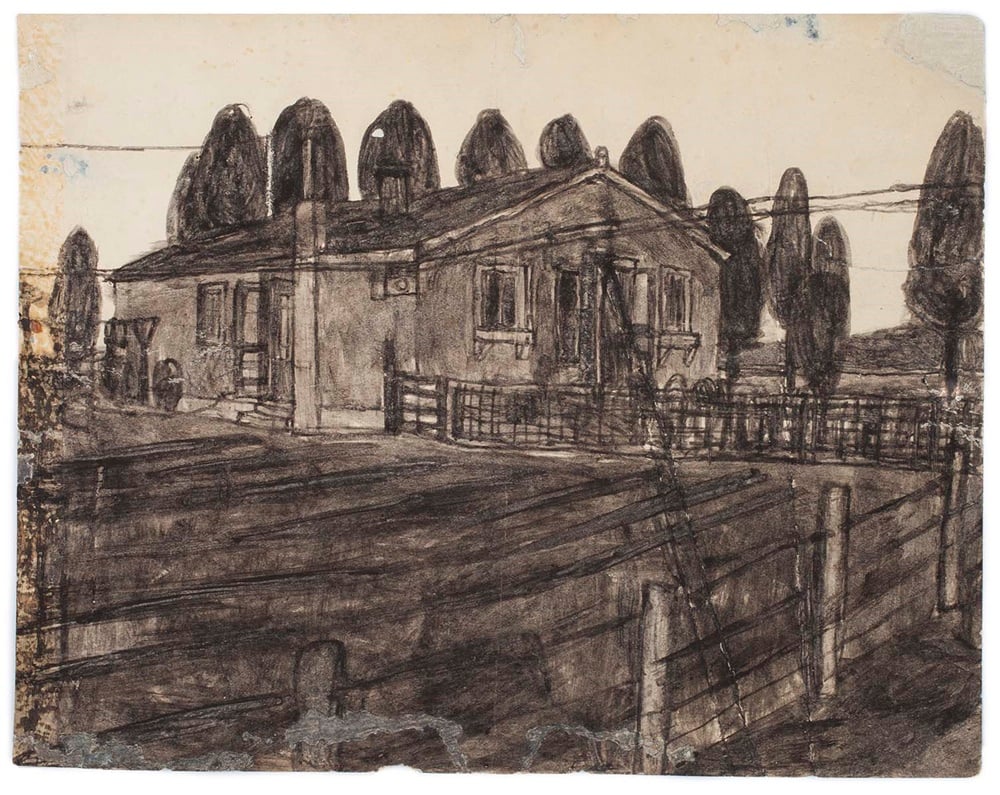

Eugene Street House in Snow. James Castle House Winter, Circa 1940 Image courtesy of James Castle Collection and Archive L.P.

Reichert describes the newly unearthed artworks as “really beautiful representations” of his drawings and other assemblages. As for what might have motivated the artist to stash the works in the walls, Reichert isn’t so sure. “It’s hard to say what the intention was. I don’t get the sense that it was a storage issue, ” she says. “It’s almost like a little time capsule.”

Castle, who was born in 1899, in nearby Garden Valley, was completely deaf. As one of seven children, he moved into the Boise house with the rest of his family in 1931. For nearly seven decades, the entirely self-taught artist made drawings, handmade books, and other assemblages, using found objects such as scrap paper and other packaging materials. It wasn’t until a nephew, visiting Boise in the 1950s, saw his uncle’s works that the artist would be “discovered” by the art world. This led to several museum exhibitions in the 1960s and ’70s. However, the real catalyst for a broader audience came with exposure at the Outsider Art Fair in the 1990s. Today, Castle is perhaps best known for his “soot and spit” drawings, works made using his own saliva.

Castle’s work has been the subject of retrospectives organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in 2008, and by Madrid’s Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, in 2011. According to the artnet Price Database, more than 50 of his works have come up for auction over the years. The highest price realized to date, is $43,750, for Untitled Construction, an assemblage of string, soot and spit, and thick paper and card. It sold at a Christie’s New York sale of American furniture, art, and folk art this past September on an estimate of $40,000 to $60,000.

Now, the newly discovered works and others by Castle will be presented to the public for the first time as project leaders gear up for the official James Castle House opening later this month. The event coincides with a major two-day symposium (April 26–27) and includes a keynote speech from Nicholas Bell, former curator-in-charge of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery. During his tenure there, Bell oversaw the acquisition of the largest public collection of works by Castle outside Idaho. The 61 Castle works will be on display in an exhibition titled “Between Board and Button,” which will run for the first year after the opening. It will be followed by a smaller group of works on permanent display thereafter.

Reichert believes it’s a fitting tribute for an artist whose home so directly—and materially—informed his work. “One of the most incredible parts of this project was to realize the connection between the house and Castle’s work,” Reichert says. “We discovered that many of the materials that Castle used in his work were quite possibly the same types of materials that were used to construct the house or to add on to the house.”