There might be no way to enumerate photographer James Hamilton’s archive. It’s way too huge, occupying an entire storage locker in Manhattan. It spans more than four decades, during which he has photographed everything from artists and parties to war zones and celebrity homes, creating images that are shot through with a loose spontaneity. Hamilton’s photos of musicians have filled one monograph and he’s toyed with the idea of compiling his pictures from film productions. But bringing together all his work in one place? “I don’t know if I can do one book,” he told me over a Zoom call. “It’s a Pandora’s box.”

For now, perhaps the best view we have of Hamilton’s hoard is in Uncropped, a new documentary directed by D.W. Young (The Booksellers). In tracing his storied career, the film resurfaces his indelible images with low-key narration by Hamilton himself. There’s a lot to unpack, not least for the photographer himself, who found the making of the documentary “illuminating.”

“I found pictures that I have absolutely no memory of taking, mostly pictures I’d taken in the street,” he said. “It’s almost as if: ‘Who took that?'”

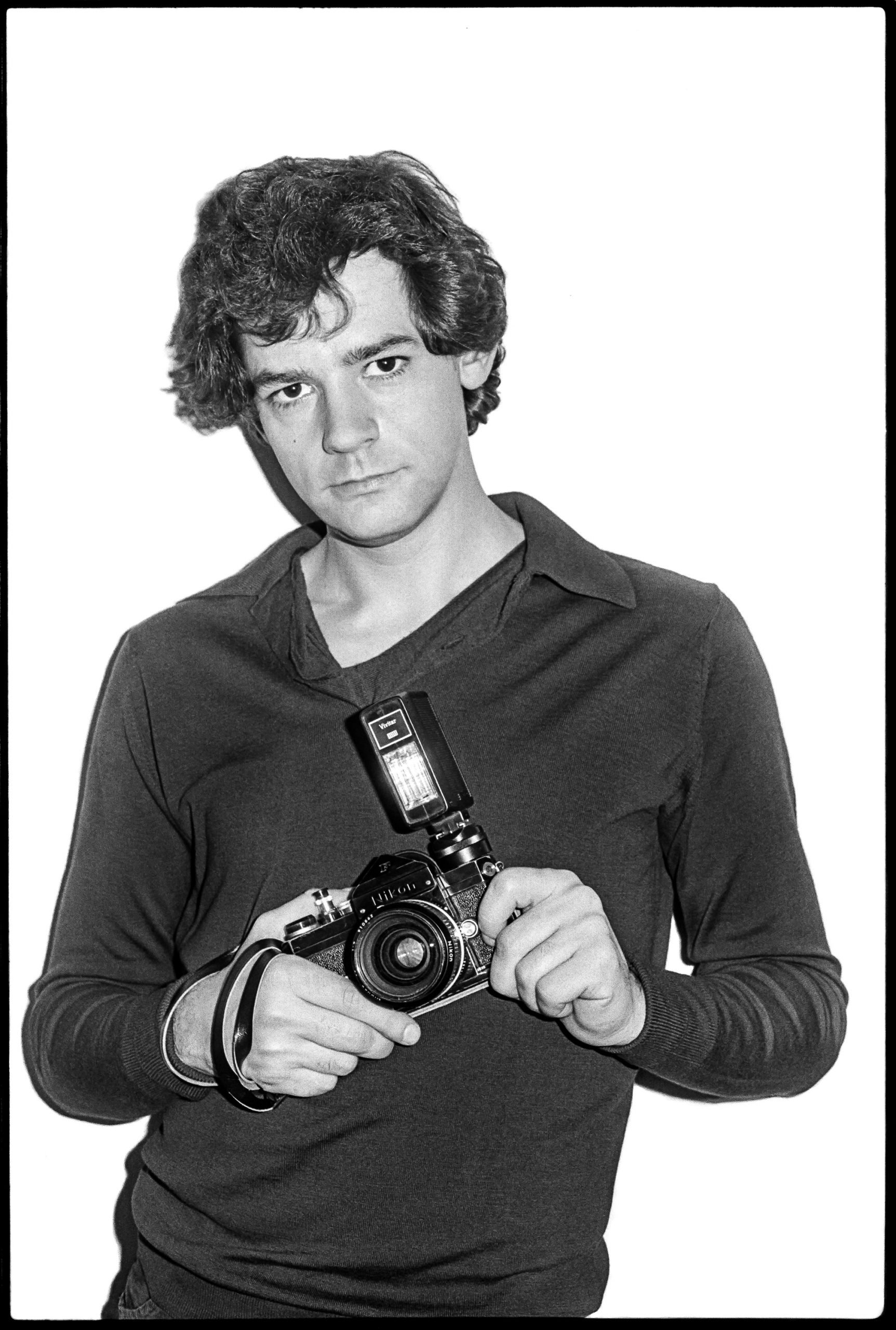

James Hamilton, Outside a theater on 42nd Street, Times Square NYC (1978). Photo: James Hamilton.

Much of Hamilton’s career has hinged on the talismanic press pass, credentials that granted him access behind the curtain of New York’s arts and cultural scene. His first was faked, though: in 1969, he mocked up a press pass to photograph performers at the Texas International Pop Festival, developed the pictures, and submitted them to music magazine Crawdaddy. Thus launched his work with a string of outlets including the Herald, New York Observer, Harper’s Bazaar, and Village Voice from the 1970s through the 2000s.

As captured in the film, Hamilton’s staff positions at these publications coincided with the heyday of print journalism. These magazines, he told me, were often generous with space, allowing him total creative control. “I basically almost created my own assignments in many cases,” he said. “I mean, the Observer had two pictures a week and I could do anything I wanted.”

James Hamilton, Patti Smith and Tom Verlaine (1975). Photo: James Hamilton.

For these publications, Hamilton would photograph a slew of figures, not limited to Jack Nicholson, James Brown, Patti Smith, Candy Darling, and Andy Warhol. In the documentary are his tales about hanging out with Duane Allman in his hotel room and attending a party where Cary Grant informed all at a table about his knife phobia. Hamilton also once showed up unannounced at Alfred Hitchcock’s St. Regis suite with a camera and press pass; the Rear Window director allowed him to fire off a few casual shots.

“I worked very fast and I talked more than I took pictures,” he recalled of his portrait sessions. “I didn’t shoot a lot of pictures, but I would engage. That was the thing really, because otherwise, the whole experience would be boring for both of us.”

James Hamilton, Alfred Hitchcock (1972). Photo: James Hamilton.

Hamilton’s work also took him farther afield. Beginning in the late ’70s, he photographed conflicts in the Philippines, Nicaragua, Haiti, and Beijing; across the U.S., he shot anti-choice protests, white supremacists, and people dying of AIDS. With writer Kathy Dobie, his partner in life and journalism, he produced visually rich stories about interracial adoption and sex workers in Brooklyn, among others. For GQ, he traveled the world photographing pinball machines, images of which made up his first book, Pinball! (1977). “I said, ‘Who wants a book about pinball?'” he told me laughingly. “It turned out a lot of people did.”

Throughout, Hamilton maintained his practice of documenting the streets of New York—one that continues today. “I had more fun doing that kind of photography than anything because it was full of surprises,” he said, adding that he found that same element of discovery when developing his photos in the darkroom. These images, like the rest of his work, are black-and-white, dynamically composed artifacts that convey an of-the-moment kineticism, a Hamilton signature.

James Hamilton, Protest in Tompkins Square Park, NYC (1988). Photo: James Hamilton.

The photographer’s compositions and effective use of light emerge from his passion for cinema, cultivated during his childhood in Baltimore, Maryland. “I’m always reminded of films because they were very important to me,” he said in Uncropped. After he first picked up a camera as a student at New York’s Pratt Institute, his dramatic frames owed an immediate debt to the films of the 1950s and ’60s. (In our conversation, he rued not working more in Hollywood, where he could have met the likes of Orson Welles.)

While photographing film sets, Hamilton would also find himself in front of the camera: he’s had cameos in Milos Foreman’s Taking Off (1971), George Romero’s Knightriders (1981), and notably, Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums (2001). Anderson, an executive producer on Uncropped, had sought out Hamilton to shoot stills on his sets, an assignment to which the photographer brought to bear his unswerving eye. “I’d rather have [him] document the movie like it’s part of the city,” the director recalled in the film, “than having someone that does things the studio is telling them to do.”

“I was photographing everything, everything around the making of the film,” Hamilton told me about his time working with Anderson. “I treated it like a documentary—that’s the only way the job becomes fun.”

James Hamilton, Muhammed Ali (May 1977). Photo: James Hamilton.

As a younger man, Hamilton aspired to become a filmmaker until he picked up photography and found himself “content with the moment.” But in many ways, his photographic oeuvre serves up narratives of its own—of New York’s cultural and social fabric, of a lifetime’s worth of work—or, as he described them in the documentary, “stories made up of moments.” They’re much like the vintage flipbooks he collects—a series of images that, when flicked through swiftly, give the semblance of movement. Hamilton, as he recounted in Uncropped, couldn’t resist swiping his first flipbook as a child.

“The irony is the first thing I ever stole was a flipbook, which combines film and stills, which is too weird,” he said. “I really do regret that I didn’t pick up a camera at that age because that’s what I believe I was born to do.”

Uncropped is now showing at IFC Center and Sag Harbor Cinema in New York, and Laemmle Royal in Los Angeles. It will be available on digital platforms from May 7.