In the mid ’70s, Adelle Lutz managed the front of what she calls the “family restaurant.” Mr. Chow in Beverly Hills was like the Studio 54 of Chinese cuisine, a glitzy convergence of all creative vectors. Lutz’s sister, Tina Chow, was married to the artist and restaurateur Michael Chow. “Everyone came in from old Hollywood to the young flashier Hollywood. I was in the catbird seat,” Lutz recalled. “I was in a position where I could observe everyone and see how they treated each other and pick and choose who I wanted to know.”

One customer stood out: a teenage David Seidner, who would regularly come in by himself. “At the time, he was very gangly and uncoordinated. He would become much more elegant,” she remembered. “He was awkward. I don’t know how we started having our conversations.” Before long, she started posing for him.

“The first photo I remember doing with him I was wearing his mother’s silk dress and lying down in their driveway,” Lutz said. “I remember it was, ‘No makeup! Only put Vaseline on your eyelids.’ And I’m going, ‘What? Why is this kid telling me I have to lie down in the driveway? It just all seemed wrong.’ And then… he took these beautiful photos. That’s when he was starting to do those segmented images, the composites.”

David Seidner, Tina Chow and Adelle Lutz, 1978. Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

“He was incredibly gifted and mature for his age, and I’m not just saying that because he was my brother,” Jaime Seidner said. “He was into photography from a very early age, and he had drug me with him to a darkroom that you could go to and pay by the hour.”

Seidner became intertwined with Lutz’s family for the remainder of his life and photographed the sisters multiple times. “I still come across these little notes and postcards that David would send to my parents from India and images,” Lutz says. “He was generous with his work. David wasn’t just a talented photographer. He wanted to have an exquisite life. His writing was very precise, very beautiful. His interiors were unlike anyone else’s. He could find the one great piece out of a total snarl of junk. He was methodical. He loved perfection. He had an eye and a rigor and an appreciation of classics. You could see that in his photography, the way he would have people pose, it tended to be very classical—like statues.”

David Seidner, Lucinda Childs, 1978. David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

New York’s International Center of Photography is celebrating its 50th anniversary with two divergent exhibitions, one sprawling, the other intimate. The first, a survey of the institution’s permanent collection, tells the story of the medium itself. “David Seidner: Fragments, 1977–99” focuses on a photographer who was best known in his lifetime for his fashion work but who maintained a parallel art practice. It’s a compelling elegy.

The show marks 25 years since Seidner died of AIDS at age 42 in 1999 and is his first stateside solo exhibition in decades. It runs until May 6 and for many will serve as an introduction. In the 1980s, Seidner had a rapid fashion world ascension. A truncated bio reads like a fairytale: a Los Angeles native decamps to Paris and by the age of 19 is shooting magazine covers and scores a multiyear contract with Yves Saint Laurent. But Seidner’s story and work are much more nuanced and complex. His legacy has diminished since his passing, but that should change with “Fragments.”

David Seidner, Francine Howell, Azzedine Alaïa (1983). Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

“I want this show to be the beginning of the retelling of his story,” said its curator, Elisabeth Sherman. She was unfamiliar with Seidner when she joined ICP last year and discovered his archive. “To open up these boxes and see this lush, highly saturated, fragmented fashion work and then see these platinum print portraits on fiber paper of incredibly important contemporary artists,” she recalled, “it felt like these were done by two entirely different people.” Sherman was moved by his scope. “He’s attached to beauty and glamour,” she explained. “He’s interested in classical sculpture and Old Master portraits. On the other hand, John Cage is his biggest influence. He’s a fashion photographer, but he defines himself as an artist. I found that duality something to celebrate.”

Seidner’s art practice informed his fashion work and vice versa. His portraits for gallery shows were hyper-stylized. He employed experimental techniques for ad campaigns and magazine spreads like shooting models refracted in mirror shards. A throughline in Seidner’s broad oeuvre is that it’s rife with art history references from the ancient Greeks to John Singer Sargent to the Surrealists and beyond, and that it’s so anachronistic that it’s hard to relegate to an era.

“From the very beginning, he’s making handmade objects,” Sherman said, “fragmenting and piecing together images. In the ’70s, he’s making portraits of John Cage, Rauschenberg, Lucinda Childs—cutting them out and taping them together by hand. Then later when the work doesn’t look as fragmented or distorted, he uses light and shadow or blurring to achieve the same effect that a broken mirror or some other earlier technique did. That cutting up of the image literally and figuratively is there the whole career.”

David Seidner, Anne Rohart, Yves Saint Laurent (1983). Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

Paris

When Seidner was in his late teens, his father died. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Paris to study art history and literature at American University in Paris (he was fluent in French, German, and Italian). Another expat, Robert McElroy, would become a friend, and for a time, his agent. “The family situation was difficult for David,” he said. “When he arrived in Paris it was closing a lot of doors, but more importantly, it was a lot of doors opening—a place where he might actually creatively and personally have a sense of belonging.”

Seidner met Gabrielle Tana through Tina Chow. Tana had come to the city to get a master’s degree in philosophy but became a music video producer (she’d segue into film). “We were kindred spirits,” Tana said. “He loved literature and art. We went to museums. I learned a huge amount from him. He was extremely erudite and sophisticated and fun and kind of difficult. He was exacting. Perfection was everything. He was intolerant for less than excellent and [had] a sense of exquisite beauty. The complete aesthete.”

“He was very social,” Tana said. “He was part of a certain kind of sophisticated gay community. He was very grown up and old before his time. There was still that romantic idea of being an American in Paris. But it was like an echo of the past. He was a romantic. I remember going to Tangiers and him asking me to take a present to [author and composer] Paul Bowles. He loved that whole sense of history and culture and it was something that he yearned for. He would seek those kinds of people out. He had enormous regard for writers and artists.”

David Seidner, Yves Saint Laurent/Violeta Sanchez (1983). Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

Samia Saoma had an eponymous Paris gallery (Robert Mapplethorpe was on her roster). “David visited several times. That’s how I met him,” she recalled. “He talked easily to people and was engaging.” Saoma became a friend and mentor and began presenting his shows in 1978. She also posed for a remarkable segmented portrait. “There was something really fresh about him and how he was working,” she explained. “These images that were cut in several sections and then put together again, it was very unusual and different from everything you saw.” Saoma never showed Seidner’s prodigious number of fashion editorials.

“Fashion was a way for him to make a living,” Tana said. “The work that really mattered was his personal work. He considered himself an artist—that was his identity. He loved fashion. There was no snobbery. He thought he was privileged that he was able to do it and loved doing it. It just wasn’t the only thing that mattered to him.”

Violeta Sanchez was a stage actress when she met Seidner at a Paris art opening. “We hit it off immediately,” she recalled. “We spoke on the phone for three hours and agreed to meet at his studio. He wanted to shoot nude pictures. He had a beautiful turn-of-the-century studio with northern light, but he was broke. It was winter and there was no heating. He wanted me naked, lying on the concrete floor, on which there were big pieces of broken glass. It was so frigid I couldn’t take one more minute of it. David was someone that didn’t press the button quickly. He always made sure that he had exactly what he wanted. I get this phone call the next day. David said, ‘I’m terribly sorry and mortified, I guess I was intimidated, but I didn’t put the film in the camera properly. Would you do it again?’ I had to laugh, and I said, sure. The pictures came out stunning.” Sanchez would become a close friend and go-to model.

David Seidner, Yves Saint Laurent/Violeta Sanchez (1983). Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

“If David had his preference, he would’ve done every single sitting with Violeta,” said McElroy. “They had a special connection. When he was shooting her, she was one of the few people that he allowed to express herself. With David, everything was so particular, the angle of the head, where the hand went—it was his vision. But he allowed Violeta to add her own energy.”

In the early 1980s, Paris was the uncontested fashion capital. It was also a time of experimentation and evolution. Rule-breaking upstarts like Thierry Mugler, Claude Montana, and Jean-Paul Gaultier redefined French chic and by the mid-decade the stars of Japanese anti-fashion Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto would shock the Paris fashion week establishment with their deconstructed mystique and dark palettes. Seidner’s work, increasingly rife with classical references and throwback allure, was more in tune with the old guard—an aesthetic alliance that allowed him to transition out of his starving artist period.

“David was very much tied to the world of Saint Laurent,” McElroy said. “He got that unprecedented contract. The elegance of Saint Laurent was a perfect marriage for David. St. Laurent was the last of a certain kind of a designer. There was never another. The world dramatically shifted after that. It was St. Laurent and Lagerfeld and then the new world started—Thierry Mugler, Claude Montana, and all those people.”

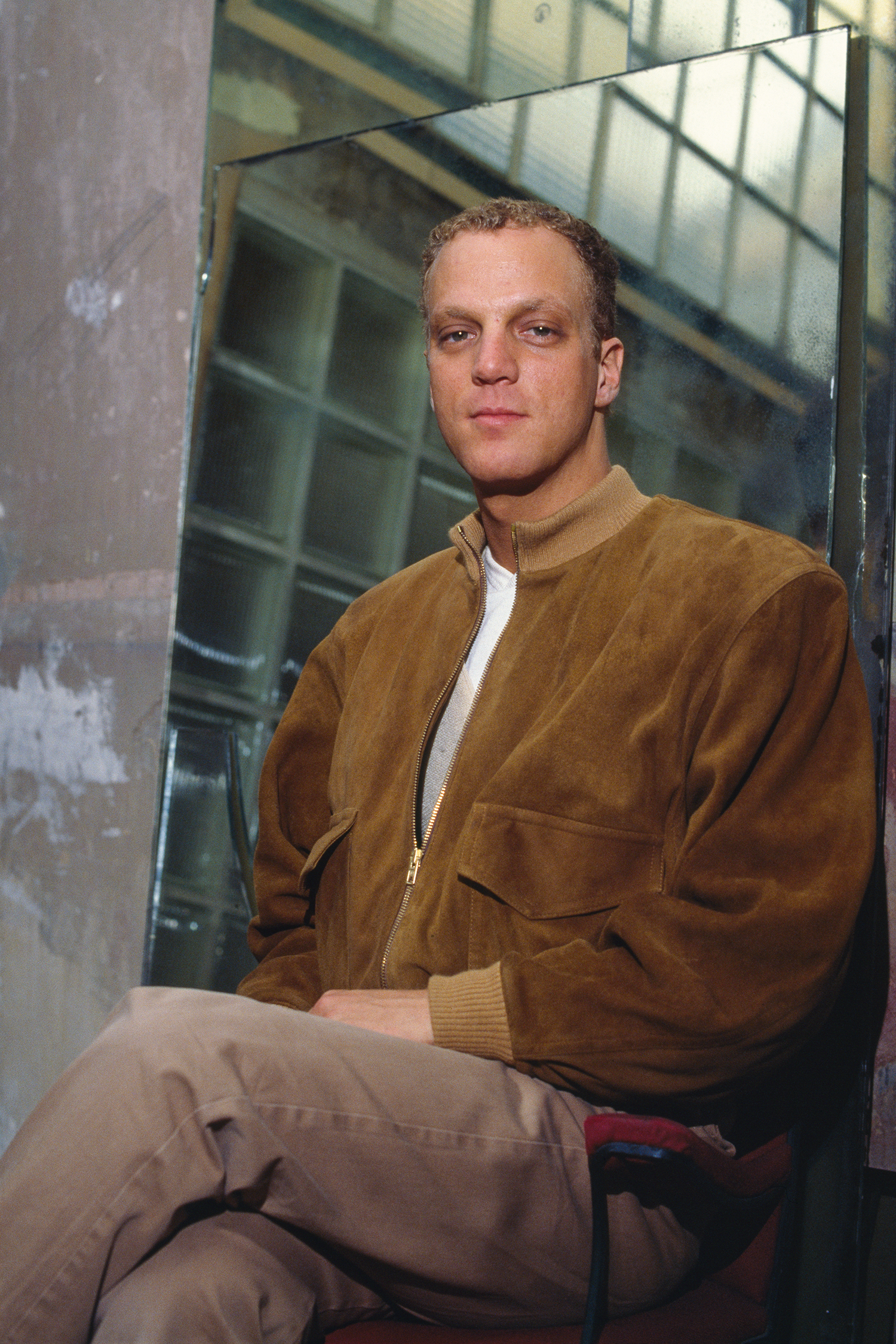

Photographer David Seidner (Photo by Robert Mitra/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images)

“It certainly wouldn’t happen now that someone like Pierre Bergé with this enormous Saint Laurent empire would just pluck a young American like David and give him a platform, but he did. It was just magical, but the world was just a very different place. There’s no analogy in where we are now. It was perfect for David that he was young at that time when those kind of possibilities were available to talent like his.”

McElroy attended the first YSL-commissioned shoot. “Violeta was of course one of the models and David did it in the courtyard of his building,” he said. “It was not at all what fashion production became. Everything was quite simple and scaled back. There was not anyone there other than David to oversee anything. The clothes arrived and it just happened. There wasn’t that team of people. The entire business changed so quickly into a completely different animal. That moment suited David perfectly where he had control over every element of what the photograph could become.”

Sanchez was intimately connected to the YSL world. “He and Helmut Newton shot the most campaigns,” Sanchez said. “In-house is not exactly the term. David became part of the family. If they liked you, they really liked you. Fashion didn’t mean anything to Saint Laurent. He was fashion. So, he did whatever he liked. Of course, he had to refresh the whole thing from time to time. They saw David’s work and that he was not just a fashion photographer. They loved when people were not just one thing.”

David Seidner, Yves Saint Laurent/Anh Duong (1986). Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

Seidner met the young ballerina Anh Duong at the Paris nightclub Le Palace. “He took my Polaroid and suddenly I was doing the Yves Saint Laurent campaign with Tina Chow,” Duong said. “Before I met David, no modeling agency would take me on. Being mixed race and looking different, everyone turned me down. David was so well-respected. Having him choose you, suddenly, your career is launched.”

“He was working mostly for European magazines. The Americans were not ready for that kind of style. He was very couture. It was a little like Erwin Blumenfeld. His style was very ’50s where women posed with a lot of eyeliner, super elegant. Which was not the aesthetic of the ’80s—big shoulders, big hair. David was very much in his own bubble. At that time, Bill King was the biggest photographer when women used to jump in the air and have their hair blowing.”

Duong was added to the Seidner’s coterie of regular models. Many were discoveries who could bring something else to the table. “He had a very small group of women that he loved and he would use them over and over,” she explained. “Tina Chow was definitely his muse. She was a married woman. She was not like a young girl just starting in life and ready to travel all over the world for modeling. She had this established life.”

David Seidner, Hat by Balenciaga (1988). Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

Seidner’s shoots were notoriously arduous. “It was purely about the aesthetic,” Duong recalled. “I adored working with him, but he was difficult. He would make you pose forever in one position. I was young, so I had the stamina. I could hold the pose forever coming from classical ballet. It was excruciating, but you knew the picture was worth it.”

“People who only worked with David saw this sort of control freak,” McElroy said. “He was not a light person to work with. But in his personal life, he could be incredibly silly and fun. When talking to people that just worked with David, they can say, ‘oh my god, he’s kind of scary.’ He was so specific. He knew exactly what he wanted before he clicked a shutter. He either saw it or he didn’t see it. In all the conversations we had over the years, I don’t recall him ever discussing what other photographers were doing. It was of absolutely no interest to him. He had his own vision.”

Colombe Pringle, the editor of Vogue Paris from 1987 to 1996, frequently commissioned Seidner. “With David, you didn’t always get what you expected, and that was wonderful,” she said. “These days people expect exactly what they want. I couldn’t work today. We didn’t care about marketing. We had no idea about all that.”

David Seidner, Yves Saint Laurent/Violeta Sanchez (1983). Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

For all of his perfectionism and control of the image, Seidner didn’t convey anodyne flawlessness. There is a sense of wabi-sabi in the images and a behind-the-curtain reveal of the grit of Paris. It belied his complexity. “His French was wonderful. He was very cultured. He knew everything about everything, whether it was design, furniture, art,” Duong said. “It was almost like he was acting. It was hard to believe he grew up in America. It was a little bit like [Andy Warhol’s manager] Fred Hughes, whom I also knew. You know, sophisticated, very in the art and fashion worlds, reinventing themselves completely like a persona, and being very social, knowing all the right people. Fred was friends with all the aristocrats. David was friends with Paloma Picasso. All the best of Paris.”

Duong continued: “He was completely not from his time. I suspect he really cut himself off from his background. People can reinvent themselves and create this whole world around what they love. And Paris was part of that. I think that David had a darker side to him, I suspect he was going wild at night. It was the ’80s. I think he was very tortured because he tortured people and he tortured himself the most.”

By the mid-decade, the onslaught of AIDS was decimating the creative spheres and hitting close to home. Tina Chow died in January 1992 at the age of 41. Seidner had learned that he was seropositive sometime in the 1980s.

David Seidner, Tina Chow/Chanel (1984). Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

New York-Miami

“There’s something strangely calming about feeling so close to the continuum,” Seidner said in a 1993 interview in Bomb magazine. “I look at a flower and I don’t think it’s any less beautiful because it only blooms for two days. I think of how green turns to black as it decomposes and how, in turn, black engenders green. This is lofty and poetic and sophomoric and clichéd, but I think about it a lot. I think about recognition and existence in very Cartesian terms. About vastness and my true insignificance in the reality of it all. I prefer to think in Eastern terms of it all being illusion.”

Seidner moved from Paris to Manhattan. Tana recalled his Crosby Street loft: “It was dark and it was sort of reminiscent of Rue Daguerre, but it didn’t have quite the same oomph. He was already sick at that point and struggling with it and going to the gym a lot. He always ate very healthy and was self-disciplined about taking care of himself. It was before there were any drugs. We lost Tina before we lost him. It was horrible. And it was also after such a glorious time. So many gifted, fabulous people were lost.”

David Seidner, Self-Portrait (1992). David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

Also coalescing was a sea change in fashion and photography built upon point-and-shoot immediacy and naturalism, with scattershot sub-genre offshoots like grunge and heroin chic. Photographers like Jurgen Teller were redefining the landscape. Seidner was even further out of step than before. “Things had moved so dramatically into a different worldview, particularly with fashion photography,” McElroy said. “It was about something happening in the moment, which is the opposite of how David worked where everything was in his mind. He already saw the photograph before it was taken, which is why he actually shot very little film. When he looked in the camera, if he saw the image that he already had in his head, it was just a matter of a few clicks. Which is completely opposite than what everyone else was doing at that time—let’s keep shooting and see what randomly happens.”

The photographer and artist Jack Pierson befriended Seidner in New York. “He had this air of hauteur, which he deserved,” he recalled. “He was also really darling when he liked you. I remember going to Odessa with him in East Village, which was a Greek diner. He wasn’t pretentious. He just seemed to have the most perfect, exquisite life.” Seidner’s work stood out for Pierson. “He was giving you old school glamor in the ’80s,” he said. “He wasn’t a household name. His work still looks contemporary today now because he was trying to do something against the grain of the time.”

Pierson sensed that it was a time of transition for Seidner. “I have no doubt he was an artist,” he said, “but there is a difference between being an artist and being in the art world. Even Richard Avedon struggled with the same thing. People weren’t accepting of the concept of art and fashion being the same thing as easily back then. And subtly, I don’t think it’s so acceptable now.”

Installation view of “David Seidner: Fragments, 1977–99”. Photo: Jeenah Moon. Courtesy of International Center of Photography, New York

Seidner leaned further into portraiture and contemporary art, blurring all of his interests. One series of nudes echoed Greek statues. He also had a decade-long project of documenting artists’ studios and taking a head-on portrait (of subjects such as Brice Marden, Cindy Sherman, Richard Serra). Many would be compiled along with his razor-sharp prose in the Assouline book Artists’ Studios (now out-of-print; it’s well-worth it if you can find a used copy). The images document the cloistered worlds of intimates like Felix Gonzales-Torres and Joan Miller, and Seidner vicariously embraces the chaos, mess, and allure of his subjects’ spaces.

Seidner also used his work to confront the AIDS epidemic in an era when just being out as HIV+ was an act of defiance and activism. He was on the board of the Community Research Initiative on AIDS and shot portraits for research campaigns. He wrote a memorable diatribe in The New Yorker decrying the empty virtue-signaling and trendiness of the ubiquitous Red Ribbon.

“When David became ill to the point where he made it clear that he just couldn’t continue the fight any longer, he spoke to Gaby and he said, you know, you are the person that needs to go to Miami with me and see me through this. Robert can’t do it, he’ll fall apart. Which would have been true. Gaby had to close her business basically. She devoted herself to being with David and seeing him through that last stage of his life,” said McElroy.

Seidner moved into a mid-century modern house on the beach. “For a long time, he was able to keep living a certain kind of quality of life,” Tana said, “and he was brave and he could do it. And then it just became too hard. He was in so much pain and he was miserable. But he fought. It was work that kept him going. And beauty.”

David Seidner, Orchid (1999) and Orchid (1999). Courtesy of David Seidner Archive, International Center of Photography © International Center of Photography

“David’s love of photography continued until his very last days,” McElroy said. “That’s when he did that brilliant series of orchids which are so outside of what you would ever think of when you look at David’s work. Those are a departure, but very much the kind of thing that you see a lot of artists at the end of their lives do—work that makes you think, where did that come from? It’s a different kind of creativity when people know that they’re near the end. Something clicks creatively and you have these magic moments.” Seidner died in June of 1999.

The orchid photos hang in the final corridor of “Fragments” at ICP. They are bright washes of soft-focus color. The blurred flowers are abstracted and inhabit two realms. Poignantly across from them on the other wall is a gauzy, dream-like black and white photo of Tina Chow. Shot from above, her hair is shorn into a Joan of Arc coif and her face is obscured and turned away from the camera. She’s wearing a voluminous 1951 Balenciaga silk cape; it flows around her and she’s walking off into the distance.