People

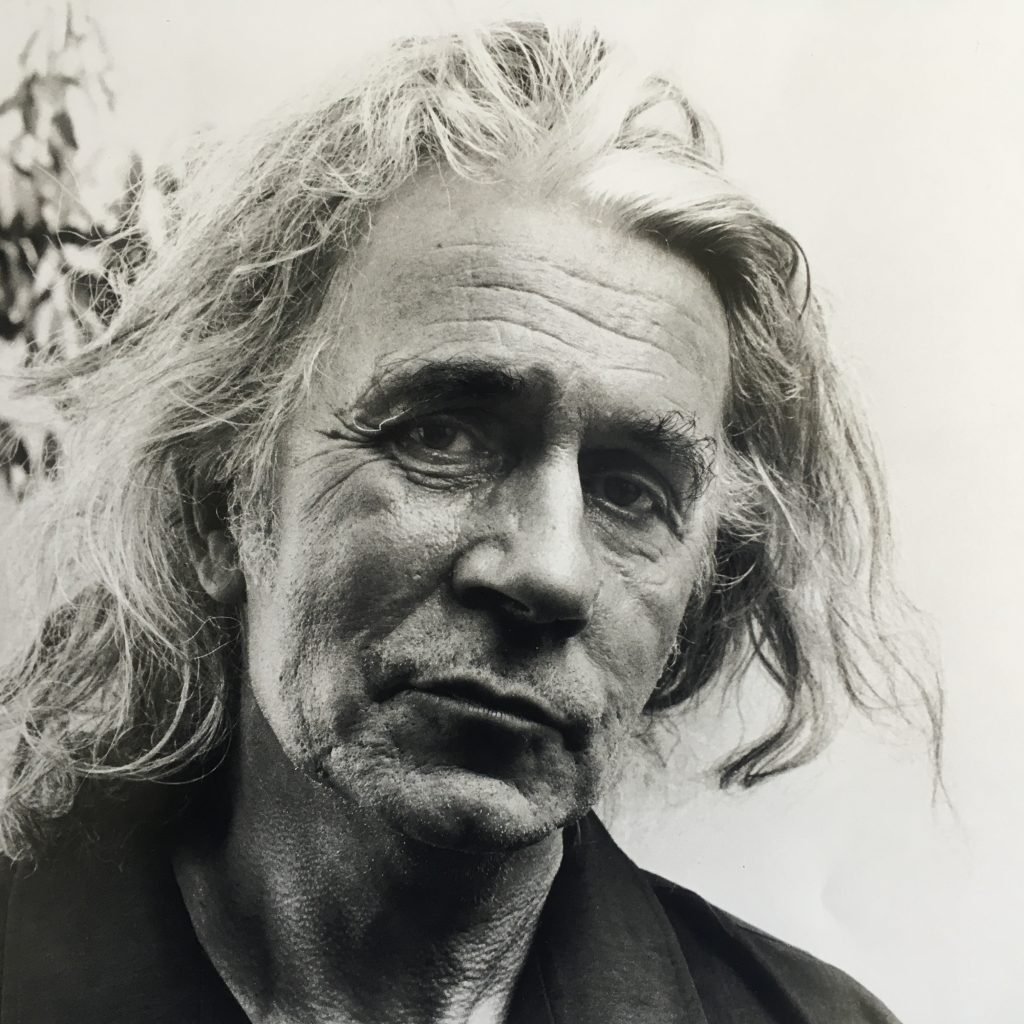

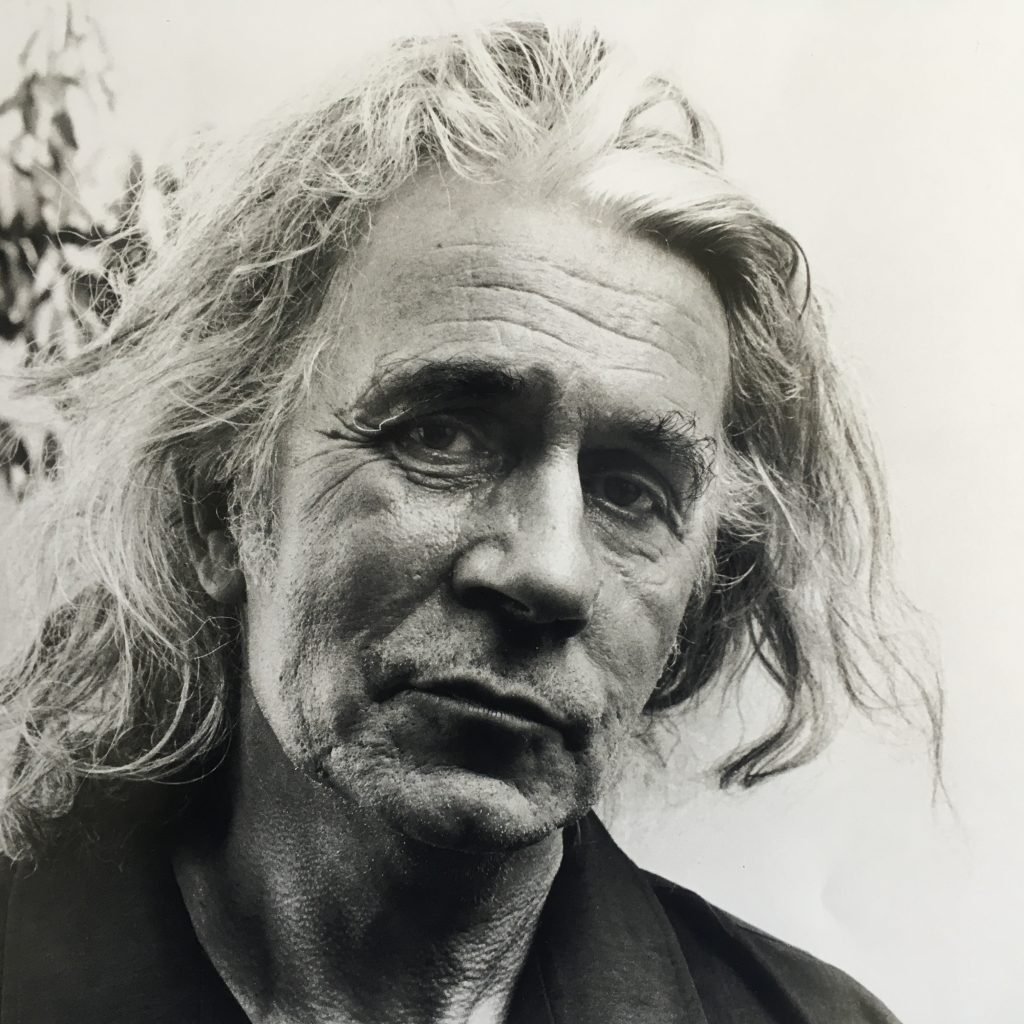

Remembering Renegade Artist Jamie Reid, Whose Subversive Designs for the Sex Pistols Defined the Look of Punk

Reid has died at age 76.

Reid has died at age 76.

Min Chen

Jamie Reid, the artist who helped define the look of punk with his brightly subversive collages and protest art, has died at age 76.

Reid’s death was first reported by Louder Than War and confirmed by his gallery, John Marchant. In a post on Instagram, the gallery remembered him as an “artist, iconoclast, anarchist, punk, hippie, rebel, and romantic.” He is survived by his daughter Rowan.

Over a career that began in the 1970s, Reid married his anarchist leanings with art, creating striking works that agitated against the establishment. His best-known designs remain his cover art and posters for the Sex Pistols; once deemed controversial, they are now collected by museums from MoMA to the V&A, priced high at auctions, and embraced by luxury brands.

“Radical ideas will always get appropriated by the mainstream,” Reid told Another Man in 2018. “A lot of it is to do with the fact that the establishment and the people in authority actually lack the ability to be creative. That’s why you have to keep moving on to new things.”

Reid was born in Liverpool, England, in 1947 to parents who were “diehard socialists,” in his estimation. At 16, on a whim, he enrolled at Croydon Art School where he met Malcolm McLaren, the future impresario behind the Sex Pistols (and “the greatest conceptual artist of the 20th century,” according to Reid). The pair apparently took part in a sit-in at the school.

Jamie Reid’s artwork, part of the Stolper-Wilson Collection of Sex Pistols memorabilia, at Sotheby’s in London on October 21, 2022. Photo: Daniel Leal / AFP via Getty Images.

Not long after graduating, Reid and a group of friends founded a community press, called Suburban Press, which produced materials ranging from anarchist cookbooks to activist pamphlets. The DIY ethos behind Suburban, remembered Reid, would prove influential to his graphic design practice.

“I probably learned more from the printing press than I did in art school,” he said in 1998. “You start developing an appreciation for what actually looks good—out of sheer necessity, from having no money. Some things gain qualities, some things lose qualities. We had to produce things really fast.”

In the ’70s, Reid was roped in by McLaren to work on a “project” that turned out to be the Sex Pistols—a band McLaren had formed by recruiting a bunch of kids that hung out at his clothing boutique on King’s Road.

Jamie Reid’s “God Save the Queen”, a machine print trial proof, part of the Stolper-Wilson Collection of Sex Pistols memorabilia, at Sotheby’s in London on October 21, 2022. Photo: Daniel Leal / AFP via Getty Images.

Over the Pistols’s brief existence, Reid would create for the band instantly iconic images including the group’s hot pink logo, the shredded Union Jack for the cover of its 1976 single “Anarchy in the U.K.,” and most notoriously, the cover of “God Save the Queen” in 1977, which featured an image of Queen Elizabeth II wearing a safety pin through her lip. Some of these album covers, in fact, were so controversial that a few shops opted to sell the records in blank sleeves.

These visuals all bore Reid’s scrappy cut-and-paste, décollage stylings that made an art out of appropriation, juxtaposition, and provocation, sprinkled with a good dose of humor and Situationist thinking. “We just went for it,” he remembered of his work with the band. “An enormous amount of spontaneity.”

Reid’s close collaborator, Jon Savage, who compiled the 1987 volume Up They Rise: The Incomplete Works of Jamie Reid, described the artist’s work to the Guardian as bottling complexity and sophistication in an “apparently simple” package. “In comparison to some of the rather tawdry and imitative punk graphics,” he said, “Jamie’s came from a deep place.”

RIP Jamie Reid, best known as the designer for the classic Sex Pistols era 1976-79. His ability to render complex ideas in eye catching visuals was their perfect accompaniment. He and I did a book together in 1987: it’s a good one pic.twitter.com/lyRSYy9L8N

— Jon Savage (@JonSavage1966) August 9, 2023

Reid’s designs for the Sex Pistols were so potent and enduring that in the following decades, the artist would even grow weary of discussing them: “I obviously do get sick of the Pistols thing,” he told the Quietus in 2011. And more so because Reid, post-Pistols, would embark on projects and activism that he felt were just as vital.

In the decades following punk, Reid would work with groups including the Dead Kennedys and Afro Celt Sound System, while designing protest art for causes as diverse as Occupy and the Anti-Poll Tax movement.

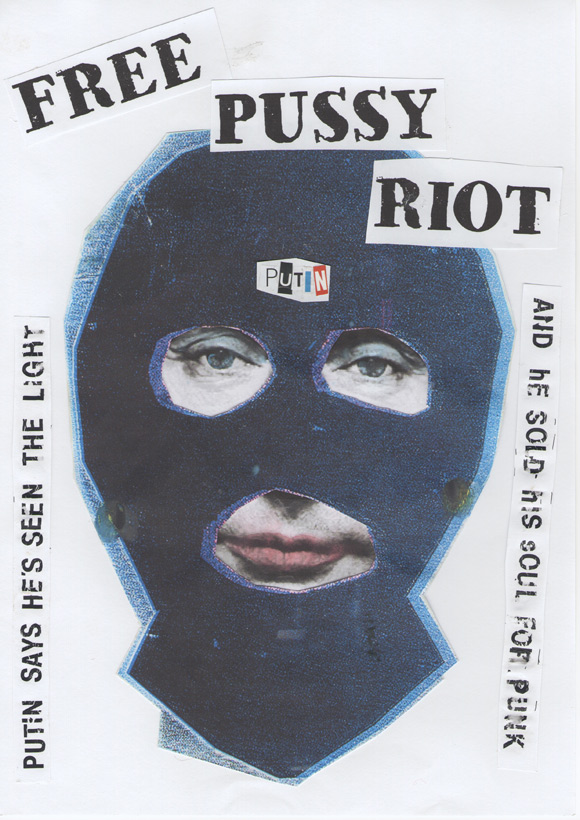

His latter-day work retained a loathing for bullies, taking aim at despotic leaders, including Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, the latter in support of Pussy Riot following the group’s 2012 arrest. In 2009, after Damien Hirst threatened to sue a student over copyright infringement, Reid turned in the pastiche, God Save Damien Hirst.

Jamie Reid, Free Pussy Riot (2012). Photo courtesy of the artist.

More recently, Reid had been delving into his Druid heritage (his great uncle George Watson MacGregor Reid was once head of the Druid Order). He created a series of swirling paintings, titled “Eight-Fold Year,” in 2015, that centered on the eight festivals of the Druidic calendar, and was working on an autobiographical film with Julien Temple about his Druid background.

His final work, Time For Magic, likewise took cues from Druid rituals. The year-long project sowed a massive Cornish field with cornflowers, poppies, corncockle, and wild carrot in the shape of Reid’s OVA glyph—a circular symbol he’d devised combining A for “anarchy” and V for “victory.” The 328-foot installation concluded its run with John Marchant in May.

“I worked with Jamie for years and years, often speaking three times a day. He was always inspiring, always said something unexpected and was a wonderful teacher,” Marchant told Artnet News. “Jamie and the art establishment were wary of each other, but in time it will all work out. As Jamie would always say, ‘Cheerio. All love.'”