People

Self-Taught Artist Jammie Holmes Didn’t Set Foot in a Museum Until He Was Over 30. Now, Collectors Are Vying for His Work

Jammie Holmes's recent rise is making him one of the hottest artists of Miami Art Week.

Jammie Holmes's recent rise is making him one of the hottest artists of Miami Art Week.

Annie Armstrong

It wasn’t until 2016 that artist Jammie Holmes even set foot inside of a museum. It was the Dallas Museum of Art, and he had just moved to the city from his hometown of Thibodaux, in rural, inland Louisiana. “It took me a month to get the courage to even go, because I didn’t know what I was supposed to wear,” Holmes told Artnet News. “I was like, I don’t have no suit, I don’t have no ties, I don’t know what the fuck I’m supposed to wear. I was freaking out…then I decide, you know what? I’m going, whatever I got, that’s what I’m going to wear. So I go to the museum and it opened my eyes—people were wearing whatever the fuck they wanted. I was like, holy shit.”

Within five years since that first contact, the 37-year-old self-taught artist’s paintings would be included in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Scantland Collection at the Columbus Museum of Art, shown far and wide from Los Angeles and New York to Italy, and selling for nearly six figures. Just this year alone, Holmes had a solo booth of his work at the Armory Show in New York and signed on with one of that art capital’s most respected dealers, Marianne Boesky.

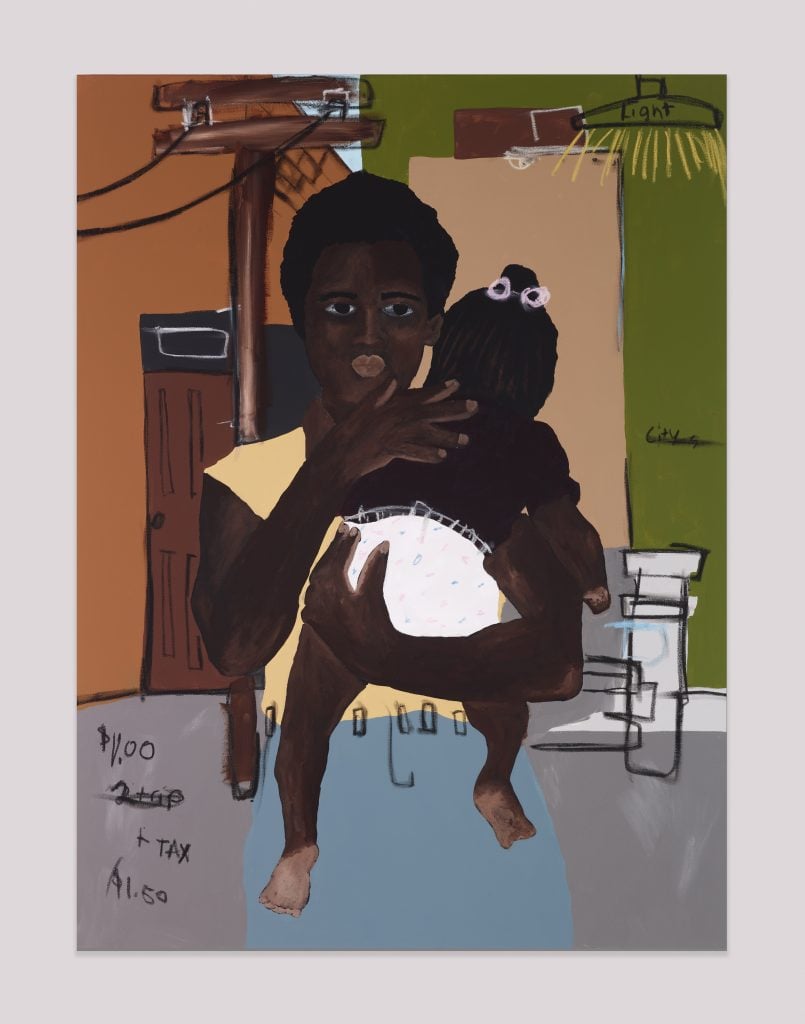

Jammie Holmes, Property Tax (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Jammie Holmes.

“For someone who has the benefit of not having been through the grind of grad school painting, there’s a freedom in his work that is special, and you can feel it,” Boesky said of Holmes. His work is largely figurative, culled from memories of his childhood as well as imagined scenes from historical events. Early works were a blend of his own experiences growing up in the rural South, where he encountered poverty and racism but also an intense connection to place and an affection for Southern hospitality. Seeing both darkness and light is a strength of Holmes’s—and one that he’s confronted with again in the art market, as his meteoric rise is both a testament to his talent, as well as another example of the market’s recent interest—and yes, exploitation—of the Black experience writ large.

“You could look at the art world any way you want. You could find the ugly of it and you could find the beauty of it,” he said. “I’ve introduced so many people to the art world you would not believe, and now they all talk about going to the museums and taking their girlfriends on dates to the New Orleans Museum of Art—I never would have thought that I was able to do stuff like that.”

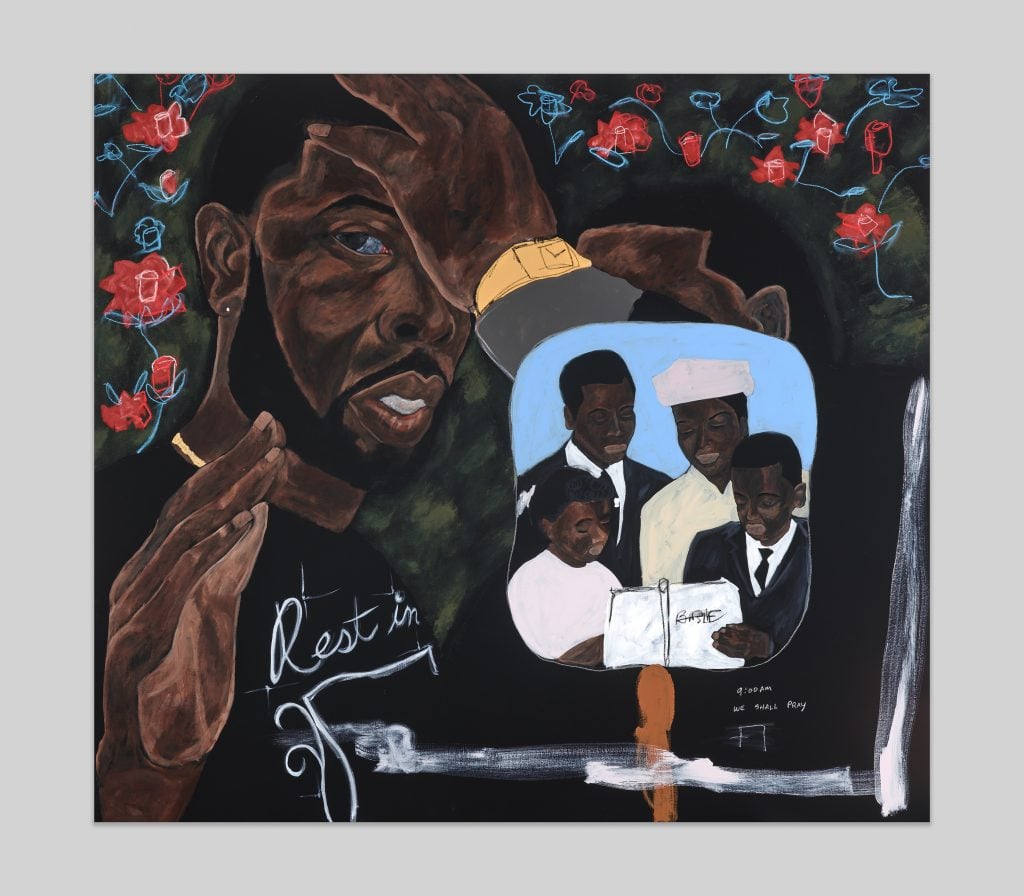

Jammie Holmes, Blame the Man #2 (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Jammie Holmes.

Likewise, Boesky is attuned to the tension between promotion and poaching, as she describes making sure to be sensitive to Holmes’s other gallery, Library Street Collective, in Detroit, which helped bring his career to the next level. “Whether I was going to be able to represent him or not, I tried to be as respectful at his gallery as possible,” she said. “I consigned work through them, and then I asked if they would do a joint booth with me at the Armory show.” At the Armory, his painting Furs and Concrete (2021) sold for $65,000.

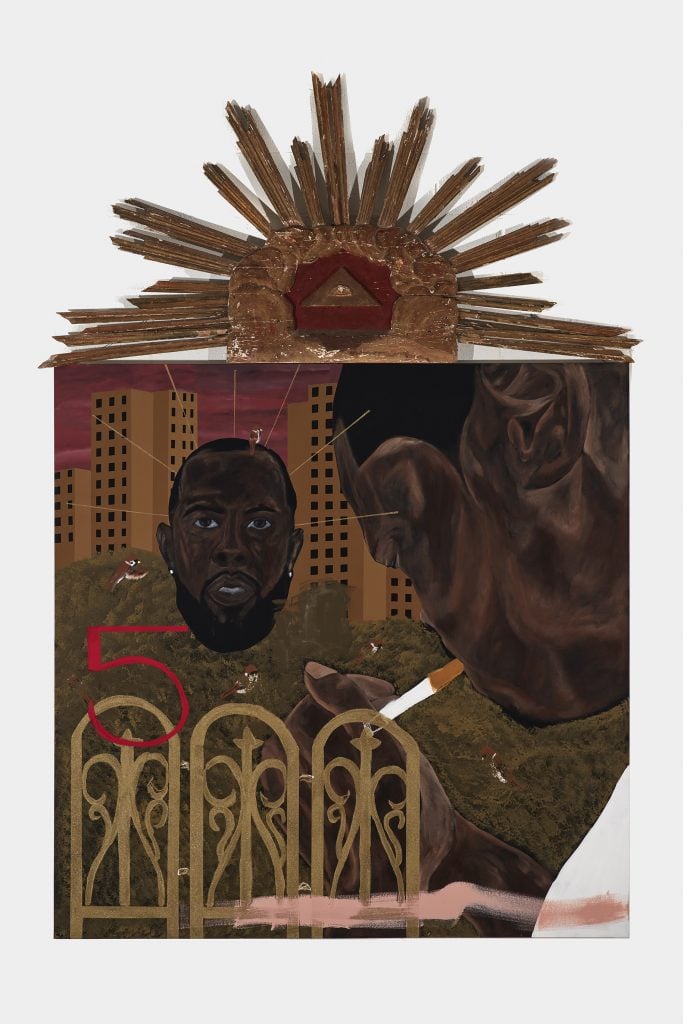

This week in Miami, Boesky is featuring a piece by Holmes, Illusions and Meanings (2021), in her booth at Art Basel. The piece incorporates a wooden sculptural element on top of the canvas, which portrays Holmes as a floating, Christ-like head in front of his late cousin, who is lighting a cigarette. “Whenever you see the painting of a person that you might know, even just knowing them from social media, it impacts you so much more,” Holmes said of the piece. “That’s your opportunity to get as close as you can to that person.”

Jammie Holmes, Illusions and Meanings (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Jammie Holmes.

Holmes has another work, Morning Start (2021), on view in the group show “Shattered Glass” in the Moore Building at the Miami Design District, co-curated by AJ Girard and Melahn Frierson, director of Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles, in an expanded presentation of a wildly successful show at the gallery this past spring.

As it stands, Holmes’ smaller paintings sell within the range of $12,000 to $15,000, and his larger canvases are priced between $85,000 to $95,000 on the primary market. On the secondary market, they are already selling for considerably more. Holmes has seen 21 works hit the auction block over the past two years; in the span of four months this spring, six of them sold for more than $100,000 each. His auction record, set at Christie’s Hong Kong in May for a 2020 painting of a Black figure in an inflatable pool, stands at $193,231.

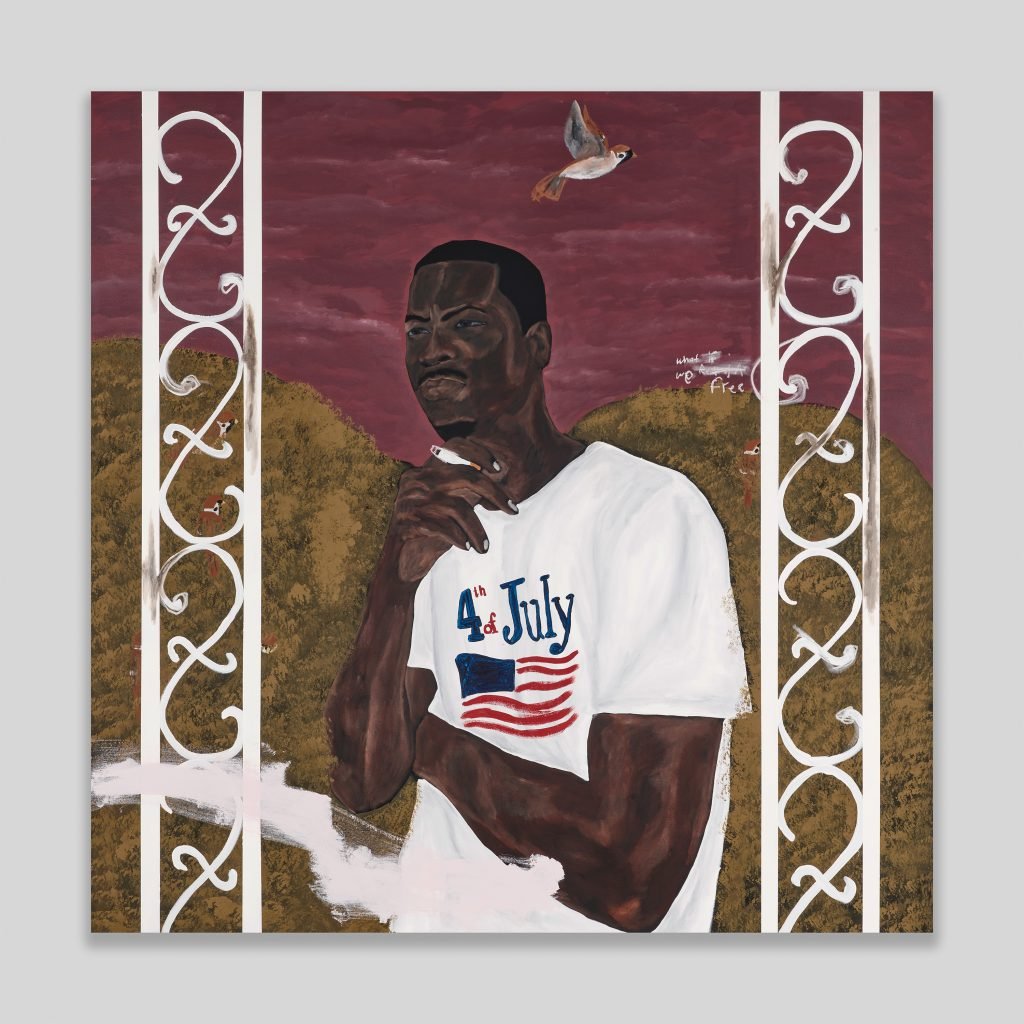

Jammie Holmes, The illusion (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Jammie Holmes.

Perhaps as a bulwark against the threat of speculation, Holmes’s current goal is singular: to get his work into museums. “With my figurative art right now, I want people to be able to go to a museum and say, ‘Wow, that looks like me, that looks like somebody that I know,'” Holmes explained. “Even if you’re white, if you’re open-minded enough, you can look at the painting and go, ‘That reminds me of one of my homeboys, that reminds me of somebody that I’m cool with.’ It makes you comfortable.”

That approach is not unlike that of an artist who serves as a direct inspiration to Holmes: Kerry James Marshall, who told NPR in 2017, “The hope was always to make sure these works found their way into museums so they could exist alongside everything else that people go into museums to look at.” While this strategy has proven fruitful for Marshall, its been an uphill battle to keep it that way at times.

For now, Holmes is optimistic about his own imminent ascent, trusting that the path paved by Marshall and others is no temporary detour. “I mean, the Black experience is in everybody’s face anyway. It’s been there—it’s been in movies, it’s been in TV shows….We’ve been studying Black people for a very long time. Now, the museums are starting to catch on.”