People

Design Wizard Jean-Charles de Castelbajac Reflects on His Pop-Inspired Collaborations With Andy Warhol and Keith Haring

We sat down with him to discuss his retrospective at Maison et Objets fair in Paris, on view January 19–23.

We sat down with him to discuss his retrospective at Maison et Objets fair in Paris, on view January 19–23.

Anthony Stephinson

French designer Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is a creative polymath with a multifaceted career spanning more than 50 years. He’s best-known for his fashion work; Madonna, Lady Gaga, Beyoncé and, most recently, Drake have all worn his pop-inspired clothing. In 2018, he was named artistic director of Benetton Group.

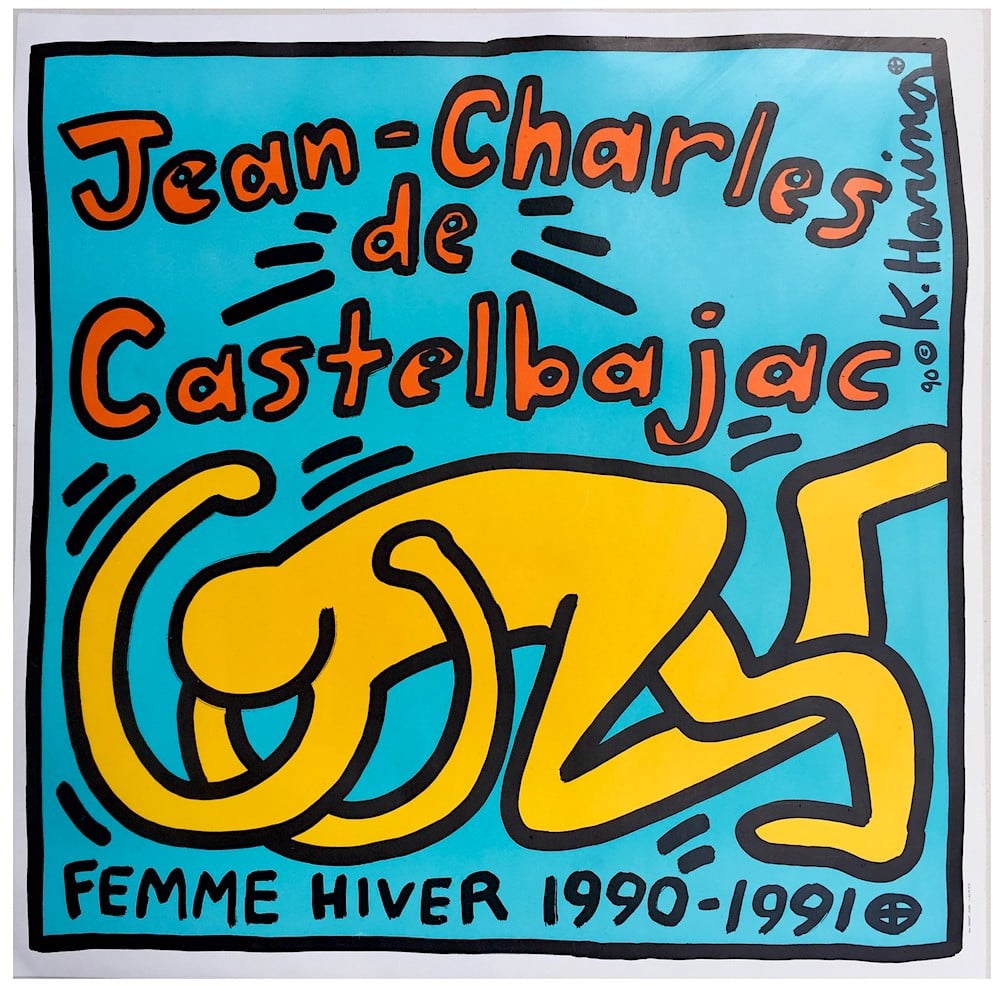

A spirit of collaboration running throughout his oeuvre is what motivates the Renaissance man, whose artistic partnerships harken back to the 1980s when Andy Warhol and Vivienne Westwood posed in his first ad campaigns. In 1990, Keith Haring created the invitation for his winter collection, one of the artist’s final drawings.

De Castelbajac’s fondness for collaboration is the focus of a retrospective at the Maison et Objet design fair in Paris. On view January 19–23, the installation shines a light on some of the brands he’s joined forces with, most notably Maison Dada, Leblon Delienne, and Thomas Dariel.

We sat down with the indefatigable designer in his Paris apartment to discuss his people-first philosophy.

I was thinking on the way here that the first time that I saw your work was at the Victoria and Albert Museum in your “Popaganda” exhibition of 2006.

Ah, yes! Unfortunately, there was no catalog made for that show, but it remains in people’s memories. What I create, I want it to become part of the universe. When I see things like Yayoi Kusama’s colored dots on the windows of Louis Vuitton, I think that I was part of the origin of that.

I will always remember a conversation I had with Malcolm McLaren when Myspace began. I told him he should join and he said, “No, we are resistant, we are underground. We must disappear and progress in hiding.” And I said, “No, we must be a pop virus. We must invade the world and use these digital tools to conquer it.” And here we are.

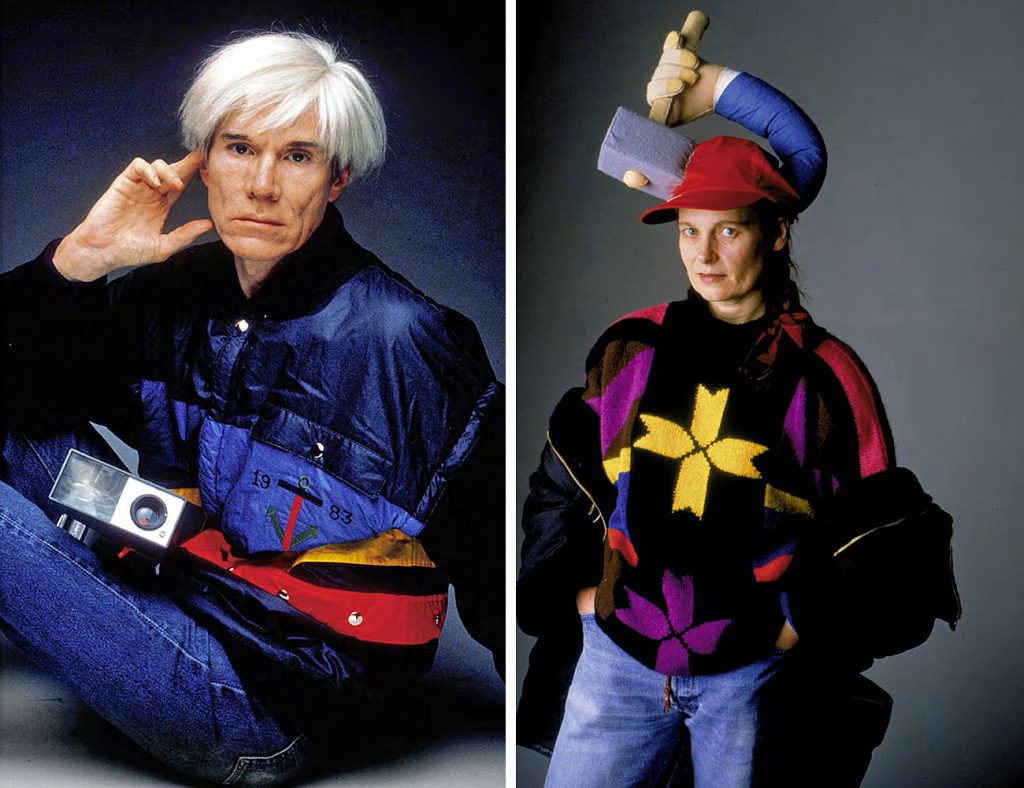

Andy Warhol and Vivienne Westwood photographed by Oliviero Toscani for Iceberg’s Les Contemporains II advertising campaign (1982). Courtesy of Jean-Charles de Castelbajac.

That also relates to the iconic photographs you made with Oliviero Toscani for Iceberg in the 1980s.

When you see those images with people like Andy Warhol, Vivienne Westwood, and Ettore Sottsass—they were the influencers of their time.

The camera jacket that Warhol wears and the hat with the hammer on Westwood communicate so much.

Yes, the simplicity and the essence of the form. When you look at the outfits I made for the Pope in 1997, with the stripes and the rainbows, this is linked to eternity. When I started to use primary colors at the end of the ‘60s, they were essential for me because I didn’t want nuance or shade. Nuance means compromise to me, so color is linked to something radical.

World Youth Days in Paris Mass, celebrated at Longchamp racecourse during World Youth Day in Paris, France, on August 24, 1997. (Photo: Antonio Ribeiro/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

You believe that primary colors are radical?

Definitely. In 1976, Roger Tallon and I were asked to work on the interior of Air France’s airplanes. We visited an aircraft and they told us, “In first class, people don’t like color. We use off-white, gray, and turtle dove. This can’t be touched.” Then we went to business class and they said, “You can’t have color here either. This is a bourgeois palette of blue marine, British green, camel, Bordeaux, and flannel gray.” Finally, we arrived in the economy class and they said, “Here you can go for it—c’est la gamme du peuple (it’s the people’s palette). The people want color.” In other words, the people have no taste. We left the meeting telling them we were going to bring color into first class, so we lost the contract. Today, 40 years later, all the luxury brands have adopted la gamme du peuple. They all use primary colors.

George Condo, Keith Haring, Grace Jones, and Jean-Charles de Castelbajac at his son’s birthday party (1990). Courtesy of Jean-Charles de Castelbajac.

Bridging high and low culture links back to Keith Haring, who you also collaborated with.

I met Keith three years before he died. He and Sydney Picasso came to my studio in 1987. Keith wanted to buy one of my teddy-bear coats for Madonna’s birthday. His presence was radiant, he filled the room. I asked my atelier to prepare a special one for him. Later we became friends. He sent me a drawing—one of his final drawings—that became the invitation to my show in 1990. But I would say the thing that he taught me the most was to be daring when drawing. Drawing was my last conquest because I am left-handed. And, here we are, I have been drawing all over the streets for the last 30 years.

Keith Haring invitation. Courtesy of Jean-Charles de Castelbajac.

When did you realize that the collaborative process was part of your DNA?

Since the beginning, my manifesto was to always put my name alongside the brand I was working with. Whether it was for Sportmax, Iceberg, Ko & Co—nobody else was doing that. Everything I did was to bring people together, that’s my obsession, my passion. My history with Maison et Objet reflects this, I want to work with French houses and reinvent the architecture of their shadows. I want to be a link, to be the continuity.

Jean-Charles de Castelbajac x Leblon Delienne. Courtesy of Maison et Objet.

What are your current projects?

For “Le Monde de Jean-Charles de Castelbajac” at Maison et Objet, I am making an installation with nine partners. Even the products from my exhibition at the Centre Pompidou are there, which is their first time at Maison et Objet.

Jean-Charles de Castelbajac’s Robes-Tableaux performance at Centre Pompidou on June 27, 2021 in Paris, France. (Photo: Francois Durand/Getty Images)

I’m also busy writing my memoir. I’m writing it as a series of short stories about the Pope, Robert Mapplethorpe, Malcolm McLaren, Vivienne Westwood, and others. But my memoir is not about memories, it’s more about activity. I want it to be an example for young people. They have to be pirates, they have to be transgressive, and they have to use the tools of the time to show their creativity.

“Le Monde de Jean-Charles de Castelbajac,” Maison & Objet, Paris, January 19–23, 2023