People

Sculptor Jean Shin on Using Live Mussels, Old Clothes, and Mountains of Dead Cell Phones to Force the Question of Sustainability in Art

Turning other people's waste into monumental works of art is her specialty.

Turning other people's waste into monumental works of art is her specialty.

Sarah Cascone

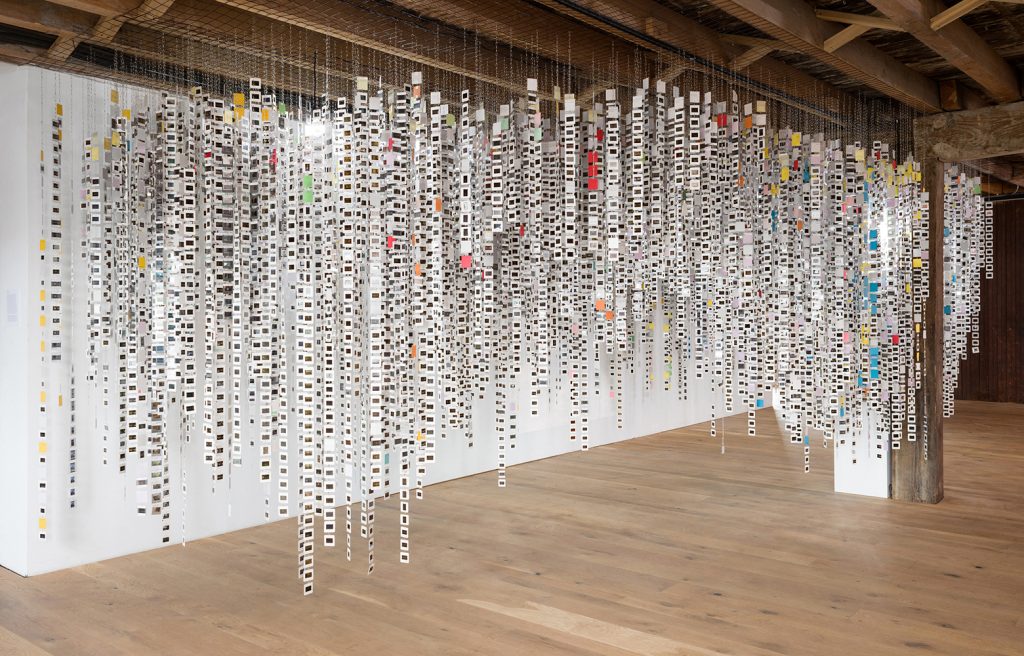

For decades, Jean Shin has made the saying “one man’s trash, another man’s treasure” into an artistic motto, transforming everything from diseased maple trees to the discarded 35mm slide archives of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art into ambitious sculptures and monumental installations.

Shin’s meticulous, labor-intensive processes shed light on the sustainability challenges we face on a daily basis—both individually, and as a society.

Splitting her time between Brooklyn and New York’s Hudson Valley, Shin took a break from her busy schedule (she’s also on the board of the Joan Mitchell Foundation) to chat with Artnet News about sustainability, how she hopes her work can inspire viewers to reexamine their own habits as consumers, and what impact our collective choices have on the environment.

Jean Shin, Allée Gathering (2019). Installation at Storm King Art Center, Hudson Valley, New York. Photo courtesy of the artist.

How did you start working with discarded materials?

As a young artist, it was just about being practical and resourceful. What do I have at hand without going to an art store and buying things? How could I transform those materials into art? That led to questioning consumerism, even as an artist.

What I gained by that was obviously savings for my pocketbook, which was great—but ultimately, I loved that the materials were so rich already. As opposed to the so-called blank canvas, these leftover materials had such a richness of stories and histories, traces of former owners that had abandoned them and of the society that had cast them off. These materials came with added associations and meanings. That’s when the work really took off for me.

Jean Shin’s Floating MAiZE in the Winter Garden at Brookfield Place, co-presented by Arts Brookfield and Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC) as part of River To River 2020: Four Voices. Photography by Ryan Muir. Courtesy of Brookfield Place

What are you currently working on?

My next project will be with the Philadelphia Contemporary, on a pier in the Delaware River, working with mussels, which have the ability to filter water. I’ll put living mussels in fountains in this very polluted Delaware river, which will filter the water and bring clarity.

I’m working with a glass fabricator on beautiful hand-blown glass to contain the mussels. I’m imagining this beautiful future that could be sustainable, where mussels could be nourished by the river.

Before we had plastic, we used mussel shells to make pearl buttons. The iridescence of pearl buttons was a status symbol, this beautiful, custom, luxurious thing. But native fresh water mussel populations were wiped out because of pearl button factories. This beautiful thing seems so insignificant, but we literally devastated mussels through consumer desire. And now we’re recognizing too late how incredibly valuable their contributions are to our clean water and the larger ecosystem.

There’s a huge effort among scientists and ecologists to try to repopulate fresh water mussels. They will literally be cleaning up the river, helping both plant life and fish, as well as helping with coastal erosion. Mussels are the foundation a larger environmental effort.

Jean Shin, Fallen (2021 ), at Olana State Historic Site, Hudson, New York. Photo courtesy of the artist.

That story of environmental loss reminds me of your piece FALLEN (2021), about how the 19th-century tanning industry destroyed the hemlock population in New York’s Hudson Valley.

Totally. Here was this mountain, full of beautiful ancient groves of hemlocks, that we deforested because we wanted leather and the tanning industry landed there. Similarly, fresh water mussels in our American rivers were devastated by the pearl button industry and our pollution of the rivers—and these little species do so much for the habitat and the landscape.

With FALLEN, a 140-year-old hemlock had died at Olana. The [Hudson River School] artist Frederick Edwin Church had planted it because he had witnessed the devastation of the hemlock trees by the tanning industry. I wanted to reckon with those two losses, of trees but also animals sacrificed to make these pelts.

So I de-barked the tree and, using leather scraps, created a second skin that would protect it like an armor. But it had a ceremonial and ritualistic presence as well. I was thinking of a shroud—clothing one would put around a dead body. This is really about mourning this tree and this beauty.

I applied the leather using upholstery tacks because, symbolically, leather and wood that would be revered would also be upholstered. Hemlocks, of course, weren’t treated this way, and all this dead stock from the fashion industry and upholstery industry would have been waste. I wanted to elevate them to the status of upholstery, something you would keep for generations.

Jean Shin, Sound Wave (2007). Photo courtesy of the artist.

You’ve done a lot of work with remnants from the fashion industry. How did that become part of your practice?

My earliest projects were using pant cuffs and deconstructing shoes and umbrellas. Fashion literally is connected to the presence and absence of one’s body. I’ve been very interested in the body, and how we fit or don’t fit fashion industry standards.

My work really talks about trying to celebrate our unique shapes and sizes. It’s so unsustainable to have new fashion every season, so I love this idea of repairing clothes and mending them to fit our bodies better. That’s also healthier for our planet.

And how do you source these materials?

They are all coming from Materials for the Arts, where fashion designers donate their scraps and remnants, whether that’s Marc Jacobs or Chloé, or even upholstery leather. So they are in the waste stream of fashion.

Jean Shin, MetaCloud at Pioneer Works, New York. Photo courtesy of the artist.

I know that for “Pause,” your 2020 show at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, you solicited people to send you their old cell phones. When did you stop just working with what you personally had on hand and seeking out the waste stream on a larger scale?

In the beginning, my focus was on found objects. Then in 2004, I was invited to have a show at the Museum of Modern Art in the project space [at MoMA QNS in New York].

For that show, I wanted to work within the community and solicit materials that would map this professional work environment and, specifically, the people who were behind the scenes. As a former museum employee, I wanted to talk about the individuals who are hidden yet so instrumental in making the institution run. I wanted to turn the gaze on this invisible workforce—not just focus on the artists themselves on the museum walls.

So I asked the curators to invite their colleagues to give me their work clothes. These were things that people had saved, but maybe were ready to let go of. It was a real donation to the project.

Installation view of “Projects 81: Jean Shin” at the Museum of Modern Art, MoMA QNS, New York. Photo by Thomas Griesel, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

I deconstructed the clothing. I was curious about how to generate a fashion pattern that would feel like a fragmented body within a collective mural made with laundry starch, with both cut outs and suspended pieces. It was like a mosaic or a collage of people’s identities that were reconstructed to fit a larger organization’s identity. In some way, they felt as if they were portraits of the museum employees.

Later on, when I wanted large masses [of discarded materials] to address the societal problem [of waste and sustainability], I realized there are organizations, recyclers, landfills, and transfer stations that are doing that deep work diverting waste.

Are these organizations surprised to hear from an artist?

It’s rare for them to work with artists and have an artist ask them for these materials. But the excitement is there, and they love that artists can amplify their work, which is what I want do. So I began to partner with these programs that are dealing with e-waste—with mobile phones, computer parts, or recycled plastics, and so on.

And that’s when my focus really became about the question of how effective recycling is. How many of our consumer goods have consequences in our landscape? How can we design better? How can we be better consumers? How can we, from the get-go, think from the point of view of sustainability.

Jean Shin, MAiZE (2017). Installation at Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Of all the materials that you’ve used, was there one that surprised you in its unexpected beauty as art?

The properties of plastic, how versatile it is, its clarity, its color—all of it really continues to amaze me. Plastic was such a major innovation when it was discovered. Unfortunately, now it’s being overused. It is so seductive, and so useful, but also so toxic and harmful to us. Consumer demand has allowed us to imagine that single-use plastics fulfill all our desires, and that they’re disposable, but they’re not. They collect somewhere.

I was first attracted to prescription pill bottles because their beautiful orange color was mesmerizing. And I’ve been working with Mountain Dew bottles, which are this beautiful green. When a light strikes this plastic, it glows tremendously. Even on the cloudiest day, it has a color and substance that is really surprising.

That green seems so natural, but in fact it is the very opposite. The soda is incredibly toxic for our bodies with its high fructose corn syrup. And then the plastic waste ends up polluting our oceans and our marine habitats. Microplastics continue to break down, creating harm for so many species and environments.

Jean Shin, Invasives (2020), installation at Riverside Park, New York City, for “Re: Growth.” Photo courtesy of the artist.

What have you made using Mountain Dew containers?

I first used two-liter bottles for an exhibition that I did called MAiZE, about how the American landscape has been transformed by corn production. High-fructose corn syrup goes in a lot of our processed foods.

The work was shown in Iowa [at the Figge Art Museum in Davenport], and was really talking about the heartland of America and corn farmland there, and our health and our environment. It was questioning what we add to our bodies and to the landscape, as pollution.

I’m also questioning my own waste stream. I saved the ends of the plastic bottles and riveted them together to create these organic forms called Invasives (2020) [which are installed outdoors]. They appear like flora on a rock, but in fact, it is one of my plastic “invasive” versions, not the native species. So, it’s thinking about plastic pollution, but also about habitat loss.

I showed it in Riverside Park [in New York City] and it’s been reconfigured and expanded, and will hug another rock formation in “Fault Lines” at the North Carolina Museum of Art, for an exhibition that deals with the climate crisis.

Is using unconventional materials labor-intensive?

When you deconstruct something, you learn so much about how it was made and how it was designed. Then, in remaking them, the beauty is really in the tension you add with every stitch. That to me is the ethos around sustainability—labor is important. It’s not about the quality of the material. It’s about the fact that it matters to you, and you want to elevate it through transformative labor.

Jean Shin, Alterations (1999). Photo courtesy of the artist.

What are some of the challenges you’ve had physically using some of these materials that are not designed for art-making?

With my recent project with mobile phones—talk about intricately designed things, all these batteries, plastic hardware, wires… To work with this precious material had a sense of danger quite literally, because if I drilled a hole in certain way it felt unstable to me. When people recycle these materials improperly, there are toxins that we’re being exposed to. It’s really challenging to work with e-waste because it is so integrally beautiful and seamless. Your phone wasn’t really meant to be deconstructed. It doesn’t break apart easily.

We were aiming for like 10,000 phones. And we had miles of cables as well, creating this immersive landscape. To me it looks like a possible dystopia. This is the future if we don’t recycle. But many people got very nostalgic for their old phones, their flip phones, that first sense of mobility from these once innovative devices that really changed our lives—but they’re also changing our environment.

As consumers, we’re continuing to upgrade constantly and to leave behind so much of the hardware as waste. We think that we’re going virtual, but in fact, all of our technological advances have a carbon imprint. It may not be seen in your drawer or in your house, but the servers that power digital life are expanding all the time. That has incredible environmental impact on climate change.

Installation view of “Jean Shin | Pause” (2020) at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. Photo ©Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Having started out working with found materials out of necessity, how important is it to you now to create work with environmentally conscious messages, with an eye towards sustainability?

It is completely important to me. What was accidental as a young artist has now become the mantra of how I make work—really asking the question of whether my practice, my materials, my techniques and processes are sustainable.

What is the most important thing that you hope people take away from a Jean Shin exhibition or a Jean Shin artwork?

Questioning their own consumer habits, their impact on the environment, and how they can invest in more sustainable green practices, environmentally friendly products, and going green in every way. Understanding how the way they choose to live is incredibly inequitable for the planet and for others who don’t get to choose how they live.

“Fault Lines: Art and the Environment” will be on view at the North Carolina Museum of Art, 2110 Blue Ridge Road, Raleigh, North Carolina, April 2–July 17, 2022.

“Jean Shin: Freshwater” will be on view with the Philadelphia Contemporary at Cherry Street Pier, 121 North Christopher Columbus Boulevard, Philadelphia, summer 2022.