Art World

‘They Want to See Blood’: Anime Superfans Wage Cyber War Against Artist Jeanette Hayes Over Alleged Copying

The artist says she received "thousands and thousands" of angry messages after a user accused her of image theft.

The artist says she received "thousands and thousands" of angry messages after a user accused her of image theft.

Rachel Corbett

In June, the artist Jeanette Hayes posted a video to her Instagram on the last day of her sold-out exhibition at New York’s Romeo gallery to show some of the anime-influenced drawings on view.

A user zoomed in on the corner of one of the drawings on Hayes’s Instagram feed and noticed that a detail of tentacles extending from young girls’ faces almost exactly matched that of a work by Japanese artist Shintaro Kago. They posted a screenshot of the detail to Reddit and 4chan and accused Hayes of image theft.

“It was wildfire,” Hayes said of the online fury that spiraled from there. “I’d look down at my phone and it was like, ‘Kill yourself, kill yourself,’” she said. Eventually, she muted the notifications, which numbered in the “thousands and thousands.”

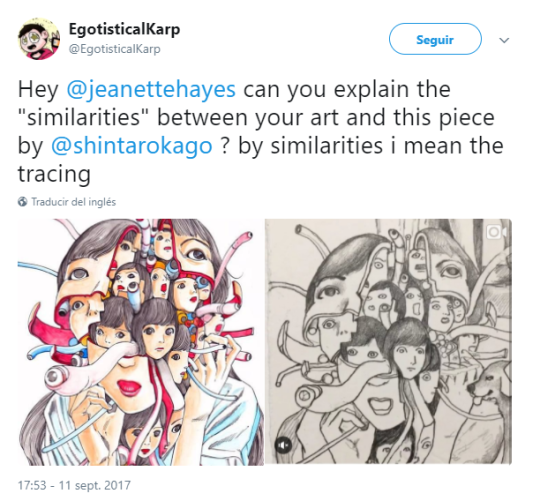

A tweet comparing a detail from Jeanette Hayes drawing with that of artist Shintaro Kago. Image: @EgotisticalKarp, Twitter.

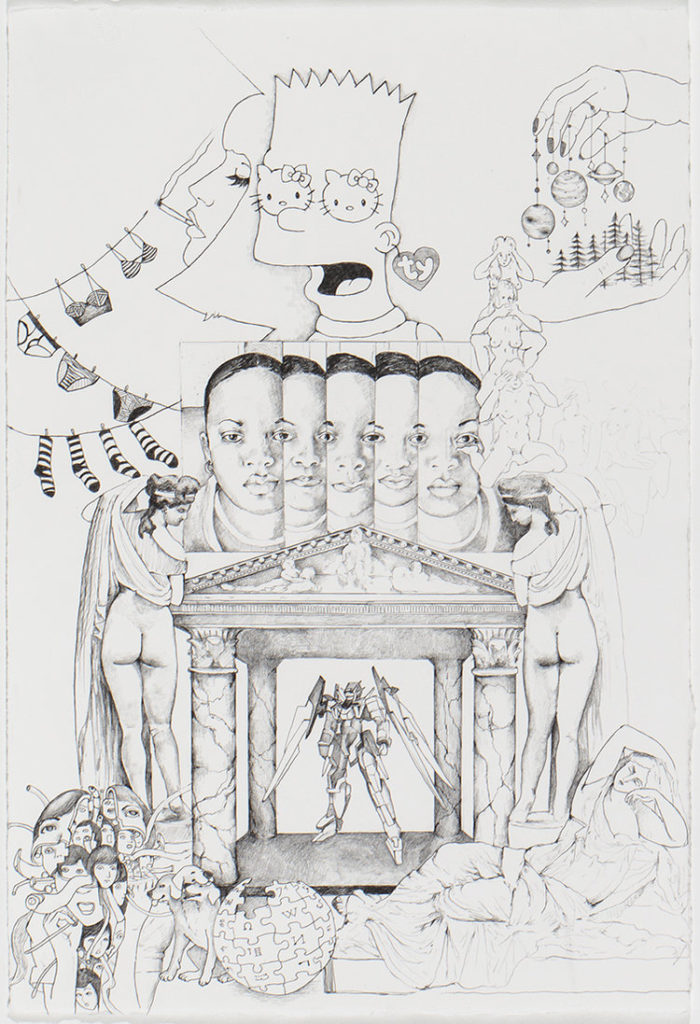

Hayes said she had pulled the image off of Tumblr years ago, as she often does, and never checked its original source. “My drawings are complex, it’s not just a 1:1 of other people’s work,” she said. Renderings of Bart Simpson, Hello Kitty, and other pop culture characters appear elsewhere in the drawing. “The show was called ‘Jeanettically Modified’ because it was all these things I was putting together.”

But the online commenters did not seem as concerned about debating the legality of appropriation art or the doctrine of fair use in US copyright law. They continued reposting the offending details of Hayes’s drawings, rather than their entirety.

The full-size drawing that came under fire at Jeanette Hayes’s June 2017 show at Romeo. Courtesy of the artist.

“It got personal,” Hayes said. They wrote to her galleries, her collectors, and to journalists who had covered her work in the past. “Someone even got my mom’s home number,” Hayes said. “A girl pretended to be me—and my mom knew it wasn’t me—but she said, ‘You raised me badly, I’m a thief, I’m a fraud.’ It was too far.”

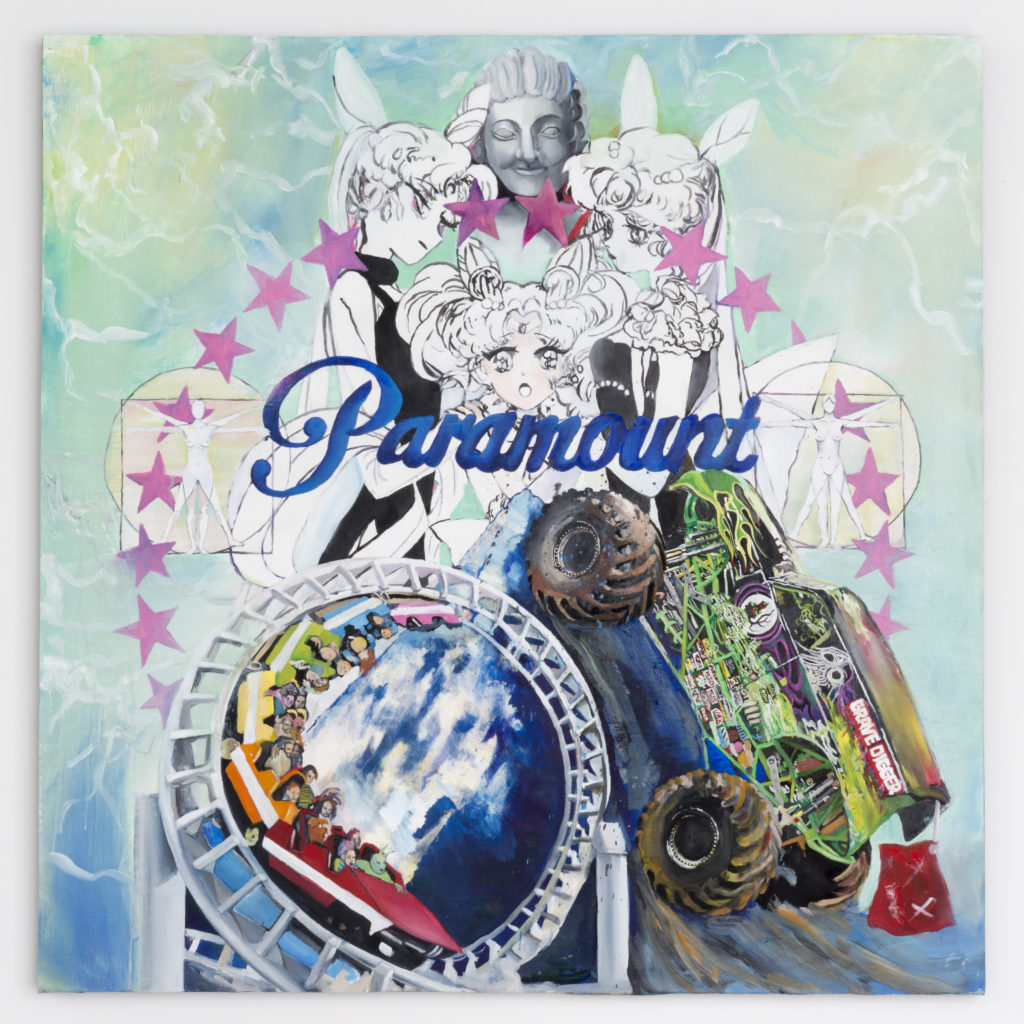

Things seemed to settle down briefly over the summer, but then Hayes reignited the controversy with the opening of her solo show at New York’s Castor Gallery last week (through December 30), titled “Despicable Me 5.” Alongside a new series of oil paintings that make reference to Michelangelo, monster trucks, and movie-studio logos, Hayes has also debuted a video in which she reads—for seven hours—the hate tweets, subtweets, and direct messages that targeted her.

“Over and over again, for hours reading about how I should be shot, how I don’t deserve to live, repeatedly called a ‘bitch’ or ‘cunt,’ and the excitement of the mob mentality about efforts to ruin my career and life,” she said. “The real anger was about me selling the work, not making the work.” Ironically, some of Hayes’s main accusers were upset about her using their images of Sailor Moon or Hello Kitty, she said. “Their interpretation of it. But it’s already fan art.”

Jeanette Hayes’s A24 cheeky (2017). Image courtesy of Castor Gallery.

So far, no legal action has been taken against Hayes, but at least one artist is considering it. A Canada-based illustrator who goes by the name Kaze-Hime discovered last month that Hayes had apparently incorporated one of her Manga-style illustrations—which included a watermark requesting it not be used for any derivative purposes—into a drawing. A social media follower of Kaze-Hime’s recognized it and “then informed me about it and commented on the Instagram post that the piece was being used without permission, but was promptly blocked,” Kaze-Hime told artnet News in an email. “Later that day, I learned the [Hayes] piece was sold on Artsy.”

“I am currently consulting advice from a few lawyers, but no definitive plans as of yet,” she added. “I do feel as though US copyright laws are making things a bit difficult.” (In the US, artists may use source material without permission so long as it is done in a “transformative” way, such as in parody or criticism.)

Castor Gallery director Justin De Demko is standing by Hayes. “At the gallery level, we did not receive significant backlash from this bullying behavior and the little we did see we simply disregarded,” he said in an email. “At the end of the day, Jeanette is making original oil paintings and drawings incorporating work from outside sources. I do not see the confusion and do not think the troll response is right or warranted.”

The debate is in some ways reminiscent of photographer Patrick Cariou’s high-profile lawsuit against appropriation artist Richard Prince, who incorporated several of Cariou’s photos of Rastafarians into his paintings. But Hayes is not interested in relitigating that terrain. “I’m not here to have a conversation about whether appropriation is OK or not. I don’t think it’s up for debate,” she said. “The yellow brick road has been paved—Richard already went to court.” (An appellate court found in 2013 that the vast majority of the Prince works in question were sufficiently transformative to count as fair use.)

While Hayes may not worry that she made any legal or ethical missteps, the battle is being waged in a very different landscape. While Prince fought his accuser in the relatively civilized realm of the courtroom, for Hayes, “this is cyber warfare. They want to see blood.”

Still, she is doubling down on her practice. “As I’ve said in the past, if you put something on the internet, it’s mine. And I mean that vice versa as well,” she said. “Anything I put on the internet is yours, too.”

Jeanette Hayes’s Paramount unmentioned (2017). Image courtesy of the Castor Gallery.