Up Next

In Painter Jesse Mockrin’s Neo-Baroque Hands, Mirrors Become Metaphors for Society’s Expectations for Women

The artist's first solo exhibition with James Cohan Gallery, "Venus Effect," is on view in New York through October 21.

The artist's first solo exhibition with James Cohan Gallery, "Venus Effect," is on view in New York through October 21.

Katie White

Venus with a mirror confounds us with merely her glance.

Throughout centuries of European art history, the goddess of love has been painted in repose alongside her mirror, casting her eyes upon her own reflection, it seems, and taking in her own loveliness. Look again at these canvases, however, and one notices that something isn’t quite right. The reflection in the silvered oval of the mirror shows the goddess’s full face, not just a sliver, as though Venus were, in reality, looking not at herself but at the viewer, or the painter in her mirror. This tangled reflection is an impossible one, and yet, this compositional trope has been repeated with such frequency in Western art as to have a psychological phenomenon, the Venus Effect, named after it.

The Venus Effect describes the human tendency to maintain beliefs inconsistent with perceivable reality; it is also the title of Los Angeles artist Jesse Mockrin’s debut solo exhibition at James Cohan Gallery in New York, a name that hints at the complexities of perception that the artist engages with. Mockrin, who is well known for her enchantingly rendered canvases that reimagine Western art historical references—Rococo, Renaissance, Baroque—here delves into the heady history of images of women at the mirror, distilling and layering these allusions in surprising compositional encounters.

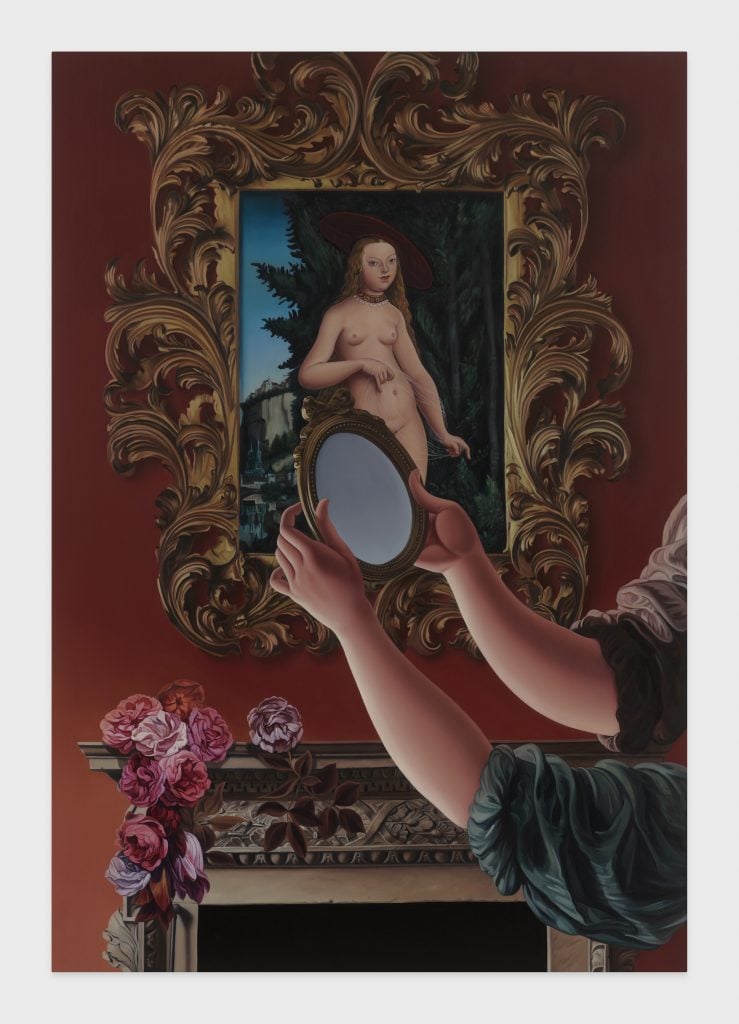

Jesse Mockrin, Enchantment (2023). © Jesse Mockrin 2023. Courtesy the artist; James Cohan, New York; and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo by Marten Elder.

Originally, Mockrin had been seeking out historical artworks of women applying cosmetics—a cunning metaphor for the art of painting—before recognizing that the true wealth of imagery lay in vanity and toilette scenes. “At a certain point in French history, men and women were both wearing the same kind of makeup. I’m interested in the parallels between the making up of a face and the painting of the face, which is how I came to this imagery,” she told me during a phone call from her Los Angeles studio. “I use makeup brushes in my practice, even. I find them quite useful.”

In the resulting exhibition, Mockrin has embraced art historical references that cross cultures, centuries, and a variety of contexts. “I’ve referenced images of Venus, of course, but also personifications of lust, and references to Biblical stories, too. One painting draws from Tintorretto’s painting Susanna and the Elders, and another painting pictures Bathsheba,” she explained.

Susanna and Bathsheba, both Jewish biblical heroines, share stories with striking parallels. Each woman is inadvertently interrupted while bathing and their radiant beauty ensnares them in prickly, dangerous encounters with powerful men. In Mockrin’s hands, these stories become windows into the ways perceptions of women can be shaped by outside forces, even habit—an everyday Venus Effect.

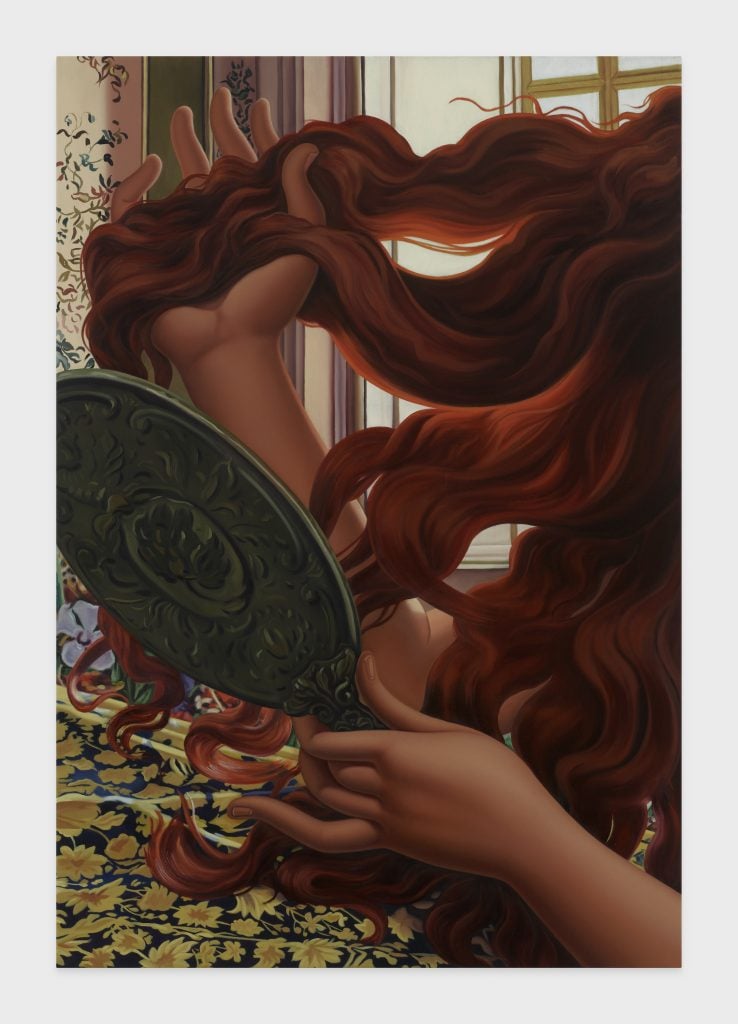

Jesse Mockrin, Echo (2023). © Jesse Mockrin 2023. Courtesy the artist; James Cohan, New York; and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo by Marten Elder.

“Most, if not all, of these paintings I reference in this show were made by men. Their depictions of women, with the mirrors, are meant to show this moment when the woman recognizes herself as the object of desire,” Mockrin explained. “It’s misogynist tradition—in depictions of Susanna and the Elders or in Bathsheba, we’re supposedly shown the moment that the woman recognizes her sexual power, which she can use over men. But actually, these paintings are not about female vanity despite the moralizing. The images are about gratification. The woman is a beautiful, seductive object to look at in the same way the painting seduces you.”

Mockrin’s compositions have, in recent years, been characterized by a Caravaggesque tenebroso with swaths of luscious, colorful fabric and pale limbs cutting across pitch-black backdrops. These compositions, often marked by fragmented forms, were the hallmarks of previous solo exhibitions at the Center of International Contemporary Art of Vancouver, Night Gallery in Los Angeles, Nathalie Karg Gallery in New York, and Galerie Perrotin in Seoul. Mockrin, who has never shied from melding pop culture references within historical reference points, even painted Billie Eilish for Vogue, in 2020, a portrait that directly referenced Caravaggio and his 1593 Boy with a Basket of Fruit. She told writer Dodie Kazanjian, “In the Caravaggio painting that inspired me, his model was sixteen years old. The basket of fruit represents abundance, youth, vitality…all things Billie has in spades. (Her works have also entered permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Rubell Collection in Miami, among others).

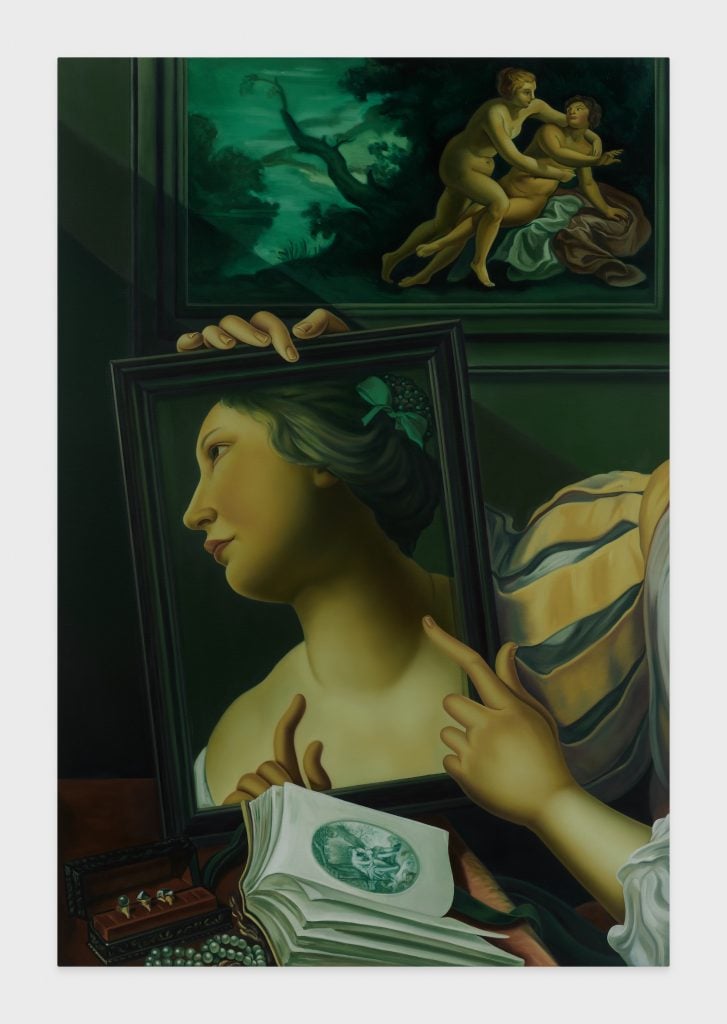

Jesse Mockrin, Sorceress (2023). © Jesse Mockrin 2023. Courtesy the artist; James Cohan, New York; and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo by Marten Elder.

But here, in “Venus Effect,” the artist charts exciting new compositional territory, even as she continues to engage with her ongoing questions of figure and form, history and the present moment. The void-like black backgrounds have given way to light, and sumptuous interiors rich with floral wallpapers, curtains, and draping textiles. “Often in my work, I’m thinking about constructed space—creating illusions and the contrasts of volumetric rendering of the people within the flat, unreal space that they occupy,” she said. “That’s still happening but there is also deeper space and perspective, which is new for me. Color and a lot of light come into these works—which means that light is sometimes different from the original references. So I’ve maybe made something backlit, or in one painting, the mirror is casting a shadow onto her face,” she noted.

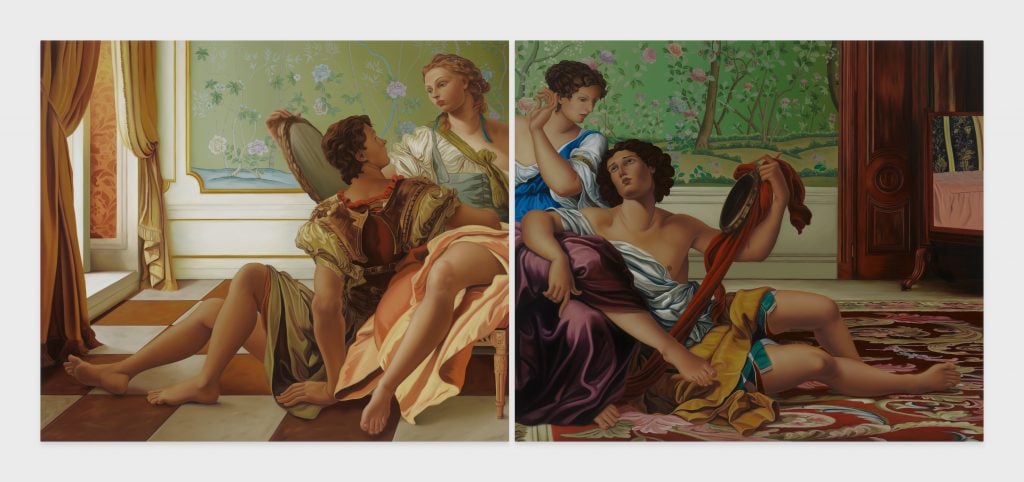

Jesse Mockrin, The lover and the beloved (2023). © Jesse Mockrin 2023. Courtesy the artist; James Cohan, New York; and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo by Marten Elder.

In The lover and the beloved (2023), the largest painting in the show, Mockrin takes inspiration from a 16th-century Italian epic poem about the Crusades. In the poem, the Christian knight Rinaldo is lured off course from his mission by Armida, an alluring witch, who ferries the knight off to an island where he must be rescued by his fellow soldiers. “In this painting, the men stare up adoringly at the women. It’s a kind of gender role reversal that I find interesting,” Mockrin considered. In many of these paintings, the feminine and masculine beauty of her figures find an almost Mannerist equilibrium—figures appear both supple and muscular, almost elastically elongated.

“I paint Mannerist hands—the fingers are missing knuckles, they’re almost tentacle-like. For me, the perversion of elegance is exciting. We see something that is beautiful but troubling,” she considered. “In painting the figures, I put multiple layers on the skin. This creates a very smooth effect and the paint sinks in and becomes this unified, matte, powdery surface. But it’s not the smoothness of youth, it’s artificial and strange.”

The constructs of gender and beauty, and how they relate to depictions of desire, particularly, play out here. “Inside the painting Reputed Fair, I’ve included a painting of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis, which is a story in Ovid’s Metamorphosis. In the myth, Hermaphroditus is this beautiful young man, and Salmacis is a woman, a nymph, who is obsessed with him, and relentlessly pursuing him,” said Mockrin. “One day he’s bathing, and she’s so overcome with lust that she dives into the water and throws her arms around him and prays to the gods that they be united together forever. They answer her prayer by making them into one being with two genders, which is where we get the word hermaphrodite. It’s a fascinating depiction of female lust.”

Jesse Mockrin, Reputed fair (2023). © Jesse Mockrin 2023. Courtesy the artist; James Cohan, New York; and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo by Marten Elder.

Other paintings are nestled within her compositions as well. Mockrin toys with space, and layering of imagery, with finesse and a sense of pleasure. “There have been fun opportunities for many pictures in a picture with this exhibition,” she said with amusement. Several of the compositions in the exhibition are diptychs, a format she has used frequently in the past. Previously, her diptychs have divided across a single figure, offering a staccato, time-lapse effect. “In these new works, I’m using the diptych as a mirror,” she explained. “The gap between the two panels is the mirror and each panel is mirroring the other, folding outwards from that inner slice.”

For Mockrin, the mirror is a metaphor for the way meaning is mapped onto the female body in the real world—not just the painted one. What we see in the painting, we reflect out into the world, with real consequences. The back room of James Cohan Gallery, in fact, is filled with drawings of women crying, a decision Mockrin made after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last year. Still, her metaphors are agile and open-ended, rather than didactic.

In developing the painting Exhibition, Mockrin found herself looking for allegories of profane love or lust in art history. “One painting showed a woman with two birds copulating on her hand. She’s looking at herself in the mirror, with a table of food and wine before her. Then on this table close to her, there’s a mysterious little bottle of liquid and a sponge. I thought, is that contraception?” Mockrin recounted. “A friend of mine suggested that the painting might be a metaphor for the life cycle and the way the female body becomes a stand-in for the entire natural order, which I think is very possible.” She allows her own works the same ambiguity.

“Reworking familiar imagery is just my way of giving history a second look,” she said. “It’s me nudging and saying let’s think about this from the point of view of our moment in time.”