On View

‘I See Color When I Sing’: Grammy-Nominated Singer Jewel on Her Turn to Painting

The musician, who turned to art for her mental health as a teenager, is the subject of a museum exhibition in the U.S.

While she may be better known for her music career, Jewel has been a visual artist for just as long as she has been singing and writing songs. Now, 30 years after her meteoric rise on the Billboard charts, she is leveraging her love of art for the next phase of her unique career.

“As a kid, drawing and words always came together for me,” the four-time Grammy-nominee told me in a video call in March, explaining how she began pursuing art around the same time that she started writing songs, between 15 and 16. For Jewel, who has synesthesia, these activities are closely related.

“I see color when I sing” she said, noting that art has helped “make sense of the world around me.”

As a precocious teen at the prestigious Interlochen Arts Academy in Michigan, she delved into philosophy, and was specifically influenced by the writings of French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal, who suggested that an understanding of shape developmentally precedes any understanding of language.

“We can relate to the idea of a circle before we ever know the word ‘circle,’” she explained, adding that this foundational recognition of form “really stuck” and laid the bedrock for her lifelong artistic practice.

Jewel was on a partial scholarship, having raised the remaining school tuition with funds won from yodeling, a skill she picked up performing with her father at hotels, honky tonks, and bars in rural Alaska, where she spent her childhood. Still, she needed a job to support herself, so she applied to be a model for the sculpting class, which was how she was introduced to marble carving—her first formal foray into fine art. Fascinated by what the teacher was explaining about plane changes, Jewel said she kept interrupting to ask questions.

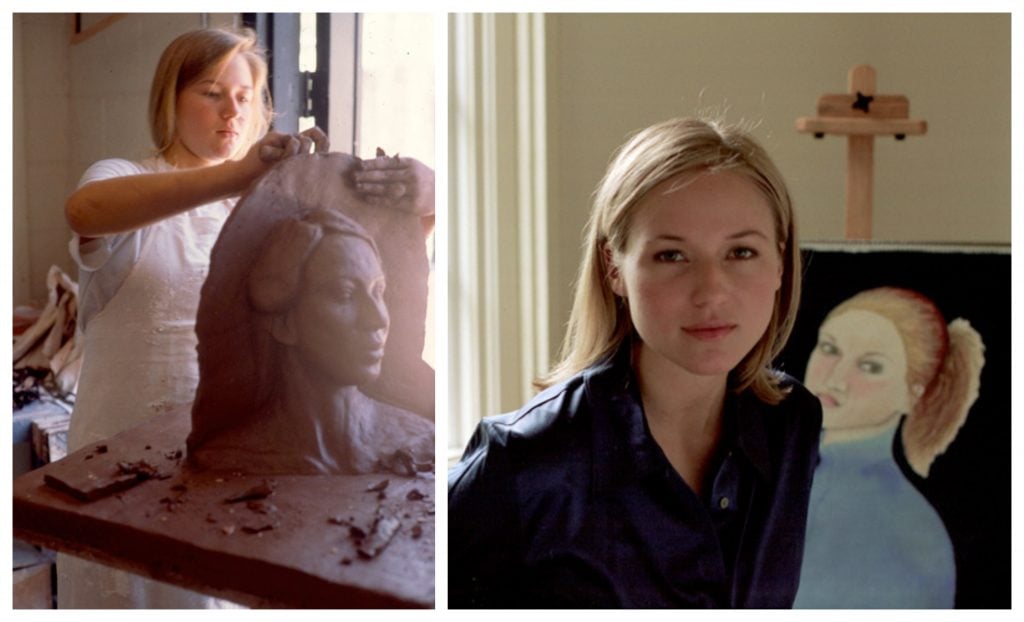

Left: Jewel in sculpting class at Interlochen Arts Academy, circa 1990. Courtesy of Jewel. Right: The singer is pictured with one of her paintings in 1997, just before her first Lilith Fair tour. Photo: West Kennerly. Courtesy of Jewel.

“Eventually [the teacher] told me I needed to stop modeling and just join the class,” she laughed.

This early experience with sculpture—both as a model and as a maker—may explain why one of her favorite artists is Amedeo Modigliani. “I was just very struck by how sculptural his painting was, and obviously his sculptures, too,” she said. “His nudes still give me chills when I look at them, they’re gorgeous.”

Taking chisel to stone proved a helpful creative outlet for the budding artist to tease out how shape “speaks to the collective subconscious” and helped her be a better songwriter, she said, adding that melody, like sculpture, “is all about form and structure.”

Carving out something beautiful from something hard was perhaps nothing new for Jewel, whose mother left when she was eight. To cope with the demands of being a single parent and his own PTSD, a product of the Vietnam War as well as his own abusive upbringing, her father turned to alcohol. At 15, Jewel decided to move out on her own as an emancipated minor with the offer of Interlochen on the horizon, a decision she details in her 2015 memoir, Never Broken.

“I knew that statistically, it wouldn’t go well for me,” she said. “Few leave an abusive house and make it on their own at 15, and so for me to feel like I could have a possible better outcome, I knew that I had to be very strategic. I needed to have a strategy for mental health, although mental health wasn’t a word then.” It was through music, poetry, and art that she was able to define a new “emotional language” to express herself more fully and change her patterns of behavior from negative to generative ones.

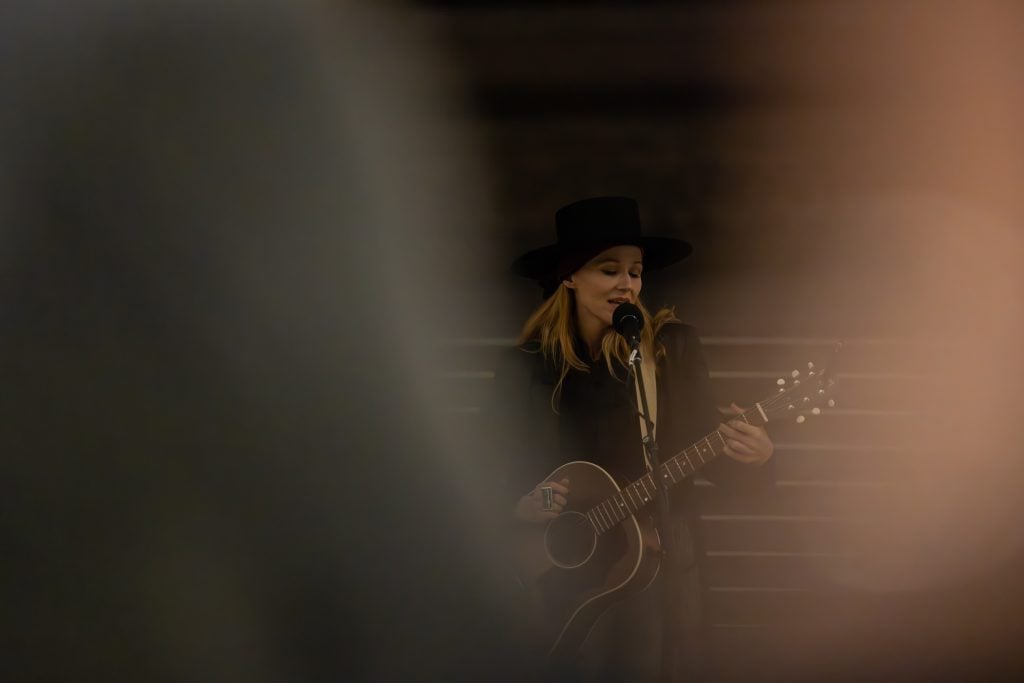

Jewel sings at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Photo: Philip Thomas. Courtesy of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

At 19, Jewel was living out of her car in San Diego, where she was playing her songs in coffeehouses, when her music career took off in the 1990s with her debut album “Pieces of You.” Her introspective lyrics and folk-infused acoustic melodies made her a best-selling artist and a fixture on the counterculture Lilith Fair scene—and provided an indelible score to my own moody early teen years.

But fame, a constant stream of multi-platinum albums, acting gigs, and a grueling tour schedule proved “toxic.” So Jewel made the decision to take a break from music in 2014, following a divorce from her husband of eight years, Ty Murray, a Texas-based world-champion bull rider and professional rodeo cowboy.

I asked her if she was able to keep making art, even amid burnout. “Yes, although I would go months without writing songs, and that would scare me,” she said. It was, after all, her livelihood. “But I also realized that, within that same time, I was always drawing.”

Using art as a rehabilitation and mental wellness tool is at the center of “The Portal: An Art Experience by Jewel,” opening on May 4 at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas. It’s less of an exhibition and more of a 90-minute accessible immersion into art therapy that museumgoers can choose to take advantage of.

Jewel and the Crystal Bridges team pictured with Retopistics: A Renegade Excavation by Julie Mehretu in the Contemporary Gallery at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Photo: Tom McFetridge. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Nestled on 120 acres of forest in the scenic Ozarks, Crystal Bridges “felt like the perfect partner” for the project, Jewel explained, noting that she approached the museum with the idea for a “takeover” back in 2022. “It’s beautiful, and there’s a real connection between art and nature there.”

Undergirding the “Portal” experience are the “three spheres,” Jewel’s take on the mind-body-spirit connection that she has developed while working with the two mental health initiatives she cofounded: the Inspiring Children Foundation, which offers mentorship and support for at-risk youths and underprivileged families, and Innerworld, a virtual member-driven mental wellness community and therapy “toolkit” of sorts.

Jewel outlines the spheres for me, noting that she believes all three need to be in harmony to find mental and emotional balance. The “inner” world is your inner life. “It’s your psychology. It’s your emotional life. It’s your heart’s desire,” she said. Then there is the “outer” or “seen” world, that includes your family, your job, nature, cities, “whatever makes up your daily environment.”

Lastly, there is the “unseen” world, which is comprised of that which exists but cannot be empirically known. “I think some people see the unseen as, ‘That’s easy, it’s Jesus,’” Jewel said. “Other people just know they get goosebumps when they see images from the Hubble telescope, or something like that. To me, the unseen sphere is just represented by awe, wonder, and inspiration.”

Museum visitors stand in front of Fred Eversley’s Big Red Sphere, a keystone work in Jewel’s “Portal” experience. Photo: Philip Thomas. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

“Portal” offers what is essentially a meditative art walk, narrated by Jewel (she even wrote the wall labels), through the museum’s contemporary wing, during which she prompts you to reflect on your relationship to the inner, outer, and unseen spheres in front of key works she selected from within the collection. Among these are paintings by Ruth Asawa, Julie Mehretu, Mickalene Thomas, and Sam Gilliam. For Jewel, Fred Eversley’s Big Red Sphere (1985) sculpture appropriately unites things.

Additionally, a hologram of the singer will greet visitors at the start of the experience and a choreographed 200-piece drone light show will happen nightly over the museum’s outdoor pond, during which visitors will be invited to wear headphones to listen to a conceptual song, also written and recorded by Jewel. (The drone show culminates in a large red heart, reminiscent of her iconic “Queen of Hearts” costume on the sixth season of The Masked Singer.)

Technology, she says, is just another tool for storytelling, just like music or painting. “If I had to sum up my artistic practice in one word, it would be ‘storyteller,'” she said. “Art is whatever I can use to tell a story.”

Left: Jewel shows the Crystal Bridges team the portrait she painted of her son Kase. Photo: Jared Sorrells. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Right: The portrait, titled Double Helix, is on view as part of “Portal.” Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Two of her own visual art creations are also on view: a portrait of her and Murray’s son, Kase, now 12, that she made after taking a two-week oil painting class in Rome last year, and a 30-inch lucite sculpture titled Chill, which depicts a person meditating and is filled with various pills and medications.

“For me, it is a conversation about wellness, culture, and the longevity of life versus the quality of life, about what it means to find balance,” the artist said of the sculpture, noting that medication can be lifesaving as much as it can be dangerous. “There really is so much hysteria and judgment around medication, and how we use it.”

I asked the singer-songwriter, actor, author, poet, activist, and now artist, who turns 50 this year, if she is finding a new level of harmony between her three spheres as she makes her museum debut and takes her visual art practice public.

“I think this is the most inspired I’ve ever been,” she said, “as if I’m back at the very beginning of my career.”