The Jewish Museum sets a high bar for itself with its new group show of modern and contemporary art, “Unorthodox.” The curators achieve mixed success in finding and defining the unconventional in the 20th century—an era, needless to say, itself defined by dramatic ruptures and radical departures—and in seeking an unconventional way to do just that.

The exhibition brings together more than 200 works by some 55 practitioners, ranging chronologically from the late German cabaret dancer and artist Valeska Gert, born in 1892, to Moroccan video artist Meriem Bennani, who’s just 27. In between are young New York painter and market darling Jamian Juliano-Villani, Sierra Leonian draftsman Abu Bakarr Mansaray, former pro skateboarder Tony Cox, and gonzo journalist and novelist William T. Vollmann, making for a varied roster.

To their credit, the curators—Jewish Museum deputy director Jens Hoffmann along with assistant curators Daniel S. Palmer and Kelly Taxter—have uncovered many artists who are unfamiliar even to art world insiders.

Installation view of “Unorthodox,” at the Jewish Museum, New York.

Photo: David Heald, courtesy of the Jewish Museum.

How, the curators wonder in a catalogue essay, could they mount an unconventional show about alternative art practices? As for the show’s defining notion of orthodoxy, of course, the title harbors an allusion to the venue, which aims to serve both audiences interested in its holdings of Judaica and ceremonial objects as well as the contemporary art crowd. What artists have escaped the homogenization imposed by an omnivorous market and a highly professionalized art education system, the curators asked themselves?

Rather than focus on the Picassos, the Paul McCarthys, and the Andres Serranos of the world, the curators aimed, they write, to shed light on lesser-known artists expressing individual sensibilities, some untrained, some non-Western.

In recent years, though, such juxtapositions have become something of a formula, with just one example being the 2011 Istanbul Biennial, co-curated by Hoffmann and Adriano Pedrosa. Museums, like the market, have gotten good at absorbing such alternative models, so the curators set themselves something of an impossible task.

“We never succinctly articulated true ‘unorthodoxy,’” Taxter laudably admits in the catalogue. Elsewhere in the publication, Ruba Katrib, curator at New York’s SculptureCenter, contributes one of a series of brief essays in a section on “the unorthodox museum.” In trying to imagine such a phenomenon, she writes, she quickly became frustrated, and in the end points out that, for one thing, “I am not convinced that clever modes of exhibition making cut it. The museum has absorbed it all.”

And the work on view hews largely to conventional formats like painting, sculpture and video, seemingly a missed opportunity to explore less easily installed forms like performance and relational work, though there are several artists working in less traditional media and formats, like Mrinalini Mukherjee’s imposing dress made out of rope, and Olga de Amaral’s shimmering works combining linen, gesso, Japanese paper and gold leaf.

All that said, the curators turned up plenty of good work, whether from market-sanctioned insiders or those who, like Philip Smith, grew up among séances and spirits, or Jeni Spota, who has relied on input from psychics, or Vollmann, who has taken drugs with sex workers and nearly frozen to death in the Arctic Circle, all according to a brochure.

Some of the artists address the touchiest subjects available, like gender and race. Challenging those categories tends to cause orthodoxies to snap into place with brutal force.

For example, English artist Margaret Harrison’s works on paper poke fun at gender norms, plopping breasts on Captain America and squeezing Hugh Hefner into a Playboy Bunny costume, leading authorities to shut down a 1971 show of her work for indecency. For his part, Brazilian-born f.marquespenteado (nom d’artiste of Fernando Marques Penteado) has removed gender identifiers from his name and works with feminine-associated mediums like embroidery to create naïve-seeming depictions of subjects like Billy the Kid.

Installation view of “Unorthodox,” at the Jewish Museum, New York, with ceramic works by Hylton Nel, foreground.

Photo: David Heald, courtesy of the Jewish Museum.

And ceramic works by Hylton Nel frankly address gay themes, with lots of erect male members and one vessel inscribed with the phrase “queer life style.” The Zambian-born artist lives in South Africa, not known as a bastion of liberation, although same-sex marriage has been legal there for nearly a decade. Vollmann’s works, though they’re fairly bad paintings, delve into similar territory, as the straight artist addresses femininity and desire via images of cross-dressing and his female alter ego.

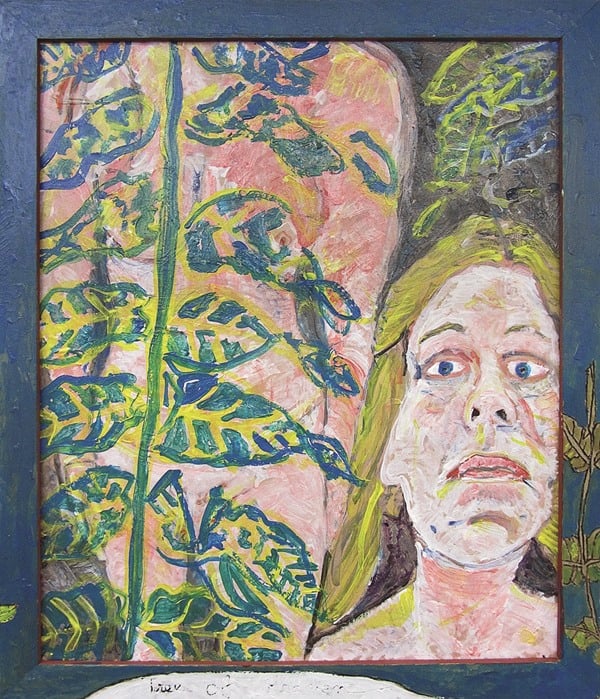

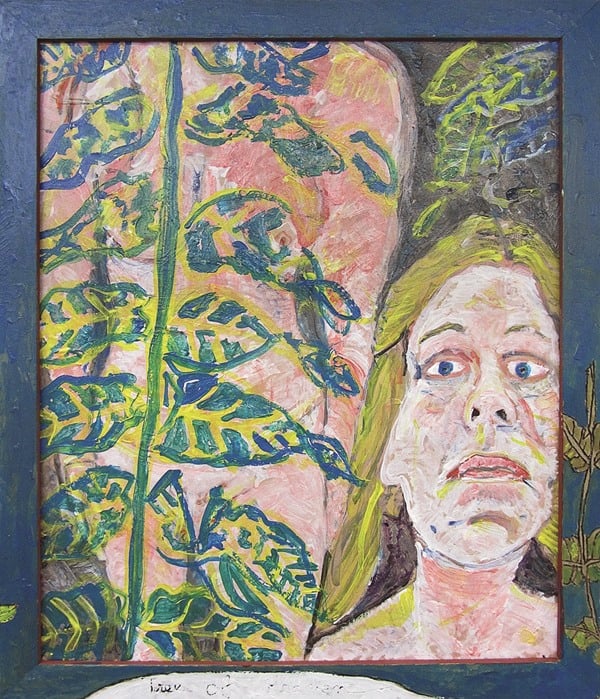

William T. Vollmann, Tree of Heaven, 2015.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist. © William T. Vollmann.

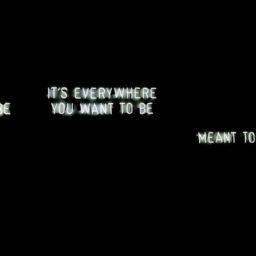

On the subject of race, the incisive soundtrack for a video by Tommy Hartung is inescapable throughout about half the densely installed show. It’s a recording of a Nation of Islam orator with a high voice and a ferocious delivery, who challenges the very notion that white people accept him and his peers as human. Against a litany of examples of exploitation, he asks, Oh, really? “When did I become a human being?”

Departing from convention can also be a high-stakes game under repressive political regimes, and several of the show’s artists have paid a price for it.

Turkish artist Gülsün Karamustafa, who was imprisoned by the military during the 1980s after having her passport confiscated for 15 years, created bold, graphic mixed-medium works on themes of political resistance; examples from the 1970s are on view, on subjects like the 1871 Paris Commune.

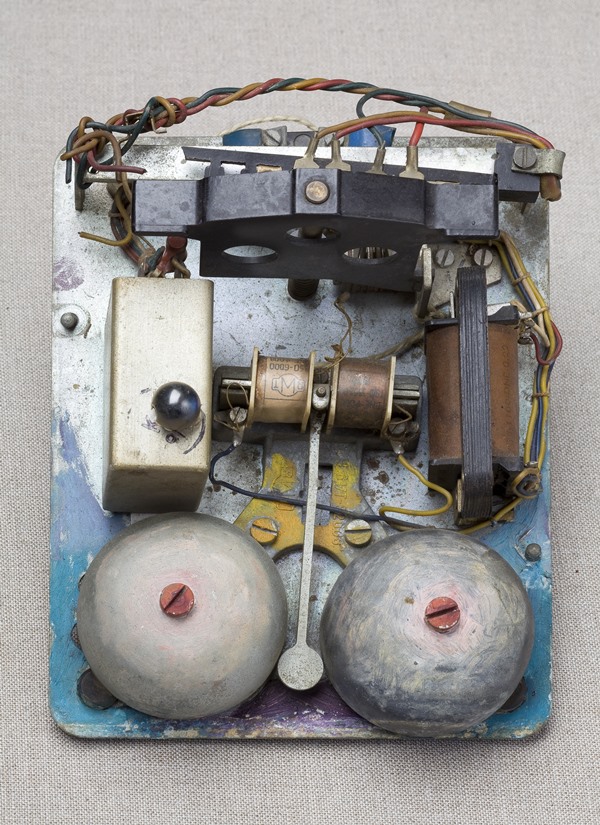

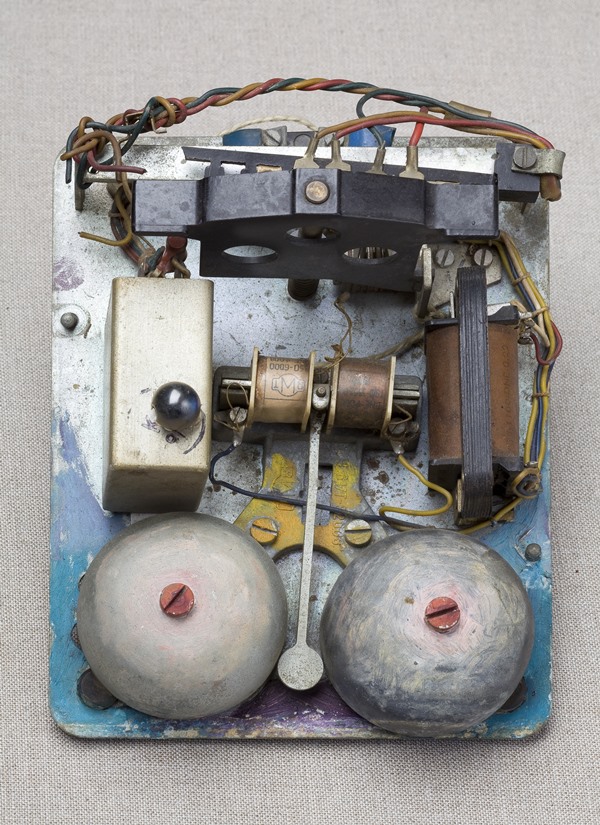

Erna Rosenstein, untitled, not dated.

Photo: © Adam Sandauer, image courtesy of Adam Sandauer and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw, Poland.

Erna Rosenstein, born in 1913 in what was then Austria-Hungary (now Ukraine), creates more understated work, judging by the example here, a tiny found sculpture in which she’s painted the inner mechanisms of a doorknob, which suggests various metaphorical resonances. That’s despite having formed an underground Communist cell in Krakow after studying painting, later being tried in court for her activities.

Zoë Paul, left to right, Speach Figures X, 2015; IC, 2015, courtesy of the artist and The Breeder, Athens; and Speach Figures C, 2015, Ahmanson Collection, California.

Image: © Zoë Paul. Photo by Will Ragozzino/SocialShutterbug.com.

Less dramatic but among the satisfying surprises are several unassuming works by young Athens-based English artist Zoë Paul.

In the works here, she weaves abstract designs in wool thread onto busted, rusty old refrigerator racks. The simple, economical gesture, while hardly revolutionary, illustrates the always-new principle that wonder can pop up anywhere, an idea that is, admittedly, only about as unorthodox as the nose on your face.

“Unorthodox” is on view through March 27, 2016, at the Jewish Museum, New York.