Art & Exhibitions

See Images of Joep van Lieshout’s Controversial ‘SlaveCity’ Project

The model city is as harrowing as it is profitable.

The model city is as harrowing as it is profitable.

Naomi Rea

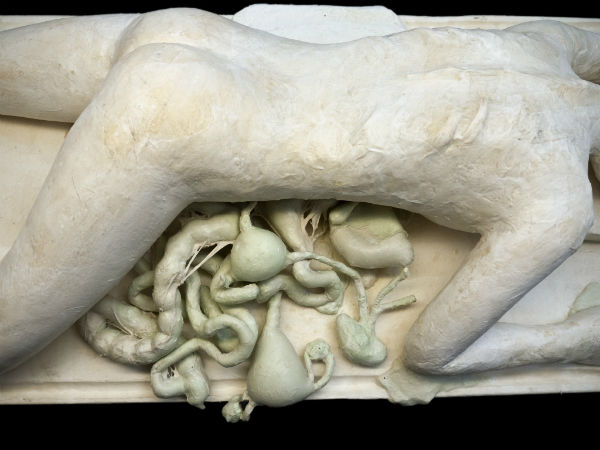

Joep van Lieshout, Woman (2009). Photo ©Atelier Van Lieshout.

Controversial Dutch artist Joep van Lieshout’s latest unorthodox installation SlaveCity, which is now showing at the Muesum De Pont in Tilburg, explores the fine line between utopia and dystopia.

SlaveCity is being shown as part of the “2016 Bosch Grand Tour,” during which seven Brabant museums are presenting special exhibitions to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the death of Hieronymus Bosch, another artist from the area known for his disturbing and critical visions of society.

Installation view of Joep van Lieshout’s SlaveCity (2005-2009). Photo ©Atelier Van Lieshout.

SlaveCity, which Van Lieshout has been working on since 2005, is a model city derived from a satirical extension of today’s dominant business models, which value efficiency, sustainability, and profit above all else. A series of models, objects, and works on paper make up the design of Van Lieshout’s imaginary city.

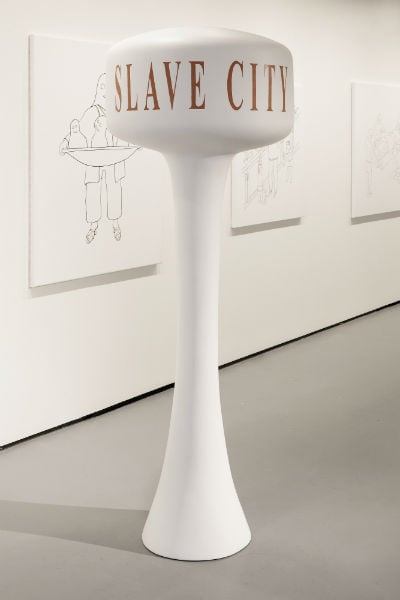

Joep van Lieshout, Watertower (2006). Photo ©Atelier Van Lieshout.

At the heart of SlaveCity are careful calculations made by the artist, which detail how putting 200,000 slaves to work in a call center for seven hours a day could net an annual profit of €7.8 billion.

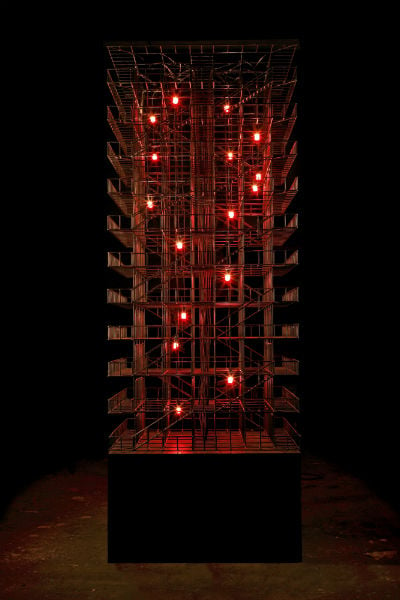

Joep van Lieshout, Minimal Steel Red Lights (2008). Photo ©Atelier Van Lieshout.

In the ambitious project—which recalls the utopian vision of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World—models, sketches, and paintings of all the buildings and installations have been realized.

Producing no waste, SlaveCity will be the world’s first “zero energy” city of its size (60 square kilometers) and, while the slaves earn no wages, expenses, housing, entertainment, and even visits to the brothel are organized neatly for them.

After manning the phones at the Call Center, inhabitants of SlaveCity must labour for a further seven hours a day in the fields or the workshops in order to maintain the city. Worker’s efficiency is monitored, and sub-optimal performance is punished. Sustainability is the watchword: everything in SlaveCity, including the organs of its residents, is recycled.

Organs, 2009. Photo ©Atelier Van Lieshout.

Van Lieshout’s work raises questions about how we live, the ties between power and corruption, and of the sinister consequences of taking the values that govern our society to their extremes.

In this latest project, Van Lieshout continues his preoccupation with questions of the autonomy of art and the artist. Can contemporary art, like SlaveCity and the rest of Van Lieshout’s oeuvre, work towards solving social problems? Or are artworks devoid of practical function and instrumental value?

Installation view of Joep van Lieshout’s SlaveCity (2005-2009). Photo ©Atelier Van Lieshout.