People

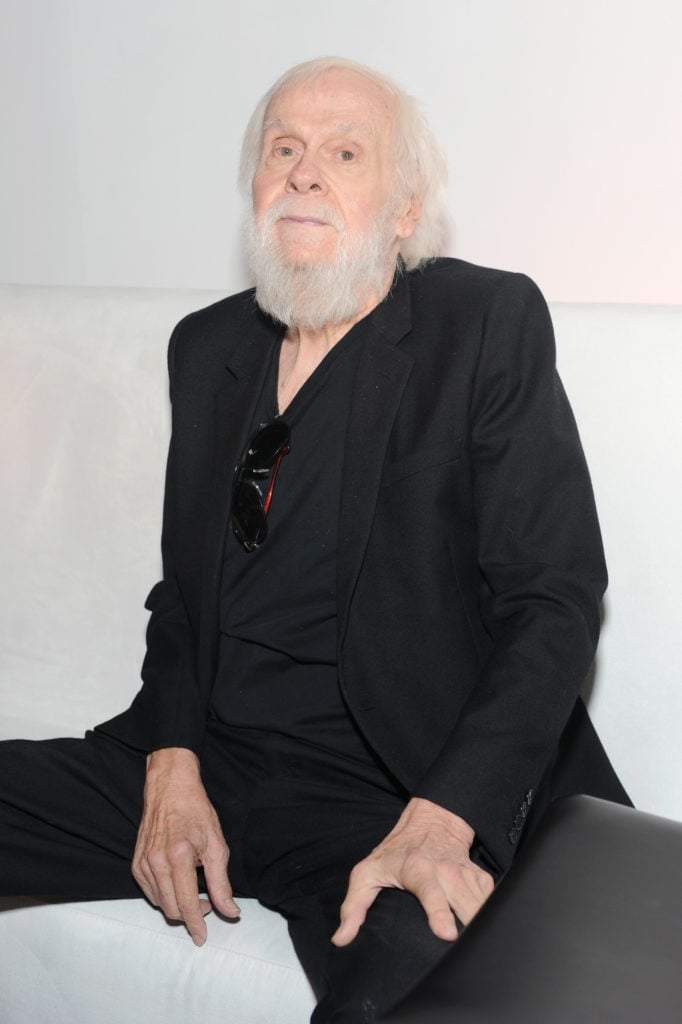

John Baldessari, the Wry Teacher Who Became a Path-Breaking Pioneer of Conceptual Art, Has Died at 88

John Baldessari was a towering figure in the West Coast art scene who inspired a generation of students.

John Baldessari was a towering figure in the West Coast art scene who inspired a generation of students.

Sarah Cascone

Pioneering Conceptual artist John Baldessari, whose droll, witty work helped expand the definition of art and shaped a generation of artists who came after him, has died. He was 88. His gallery, Marian Goodman, confirmed his passing, though a cause of death was not immediately available.

The subject of over 200 solo exhibitions worldwide, Baldessari was a towering figure in contemporary art both literally (he was six feet, seven inches tall) and figuratively (he won numerous honors over the course of his career, including the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2009 and the National Medal of Arts).

The artist’s international fame also transcended the art world, earning him a cameo on The Simpsons in 2018—Baldessari did his own voice acting work, appearing at a gallery opening that is disrupted when a baby Bart Simpson destroys a sculpture.

Born in National City, California, in 1931, Baldessari was drawn to art from an early age, earning an MFA in 1957 at the current-day San Diego State University. He was a dedicated educator who started out teaching high school and eventually went on to hold prestigious posts at CalArts, UCLA and UC San Diego, instructing students including Mike Kelley, David Salle, Barbara Bloom, and Matt Mullican.

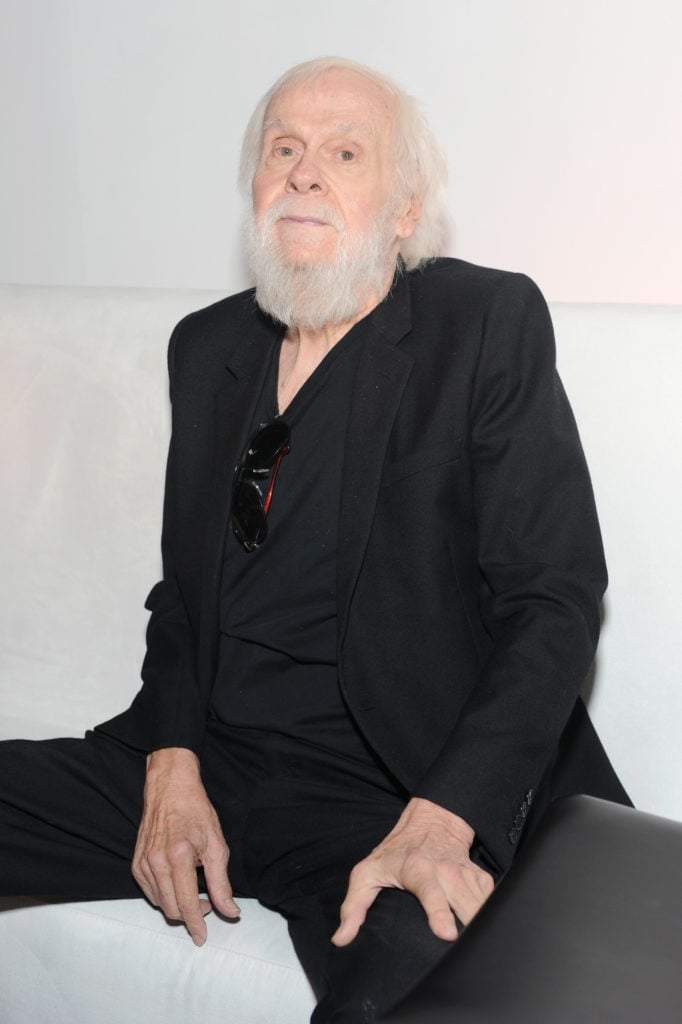

John Baldessari, Hot and Cold. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.

As a teacher, he did much to shape a now-mature generation of artists coming out of Los Angeles, who learned from his anything-goes attitude and accessible packaging of high-minded concepts. In a 2003 interview, he said of his teaching philosophy: “I set out to right all the things wrong with my own art education. But I found that you can’t really teach art, you can just sort of set the stage for it.”

Baldessari—who remained mild-mannered and good humored even as his star rose—found success as a teacher before he gained acclaim as an artist. His first major work, in 1970, involved destroying everything that had come before in a dramatic piece of performance art titled The Cremation Project. Baldessari burned every painting he had made between 1953 and 1966 and baked the ashes into cookies that he displayed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York’s 1970 Conceptual art survey, “Information.”

It was a rejection of what he had been taught, that “painting and sculpture were the only acceptable forms of art,” Baldessari told the Wall Street Journal. Though he counts Giotto, Goya, and Henri Matisse among his favorite artists, he felt called to push the bounds of art. In doing so, he helped give birth to the Conceptual art movement. Years later, the Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight would describe him as “arguably America’s most influential Conceptual artist.”

![John Baldessari, Frames and Ribbon [detail] (1988). © John Baldessari.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2019/04/top-half-john.jpg)

John Baldessari, Frames and Ribbon [detail] (1988). © John Baldessari.

From that point on, the California artist was driven by the desire to find his own answer to the age-old question of what is—or is not—art. On that quest, Baldessari delved into mass media culture, hired commercial sign painters to execute his works, created influential paintings that paired text with images, and appropriated everything from Old Masters to film stills to emojis. (A common motif in his work was obscuring people’s likenesses in found photographs with colored circles—he once lamented that he’d be remembered as the “guy who put dots over people’s faces.”)

John Baldessari, Ocean and Sky (with Two Palm Trees), 2009. The artist covered the facade of the Palazzo delle Esposizioni with laminated wallpaper on the occasion of being honored with the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. Photo courtesy of the Venice Biennale.

“I get bored easily,” Baldessari admitted during that Venice talk. “I like to do things that I’ve never tried before.” He was talking specifically about the sky blue makeover he’d given the biennale’s main exhibition hall—leaving the columned structure looking, as he put it, like a Roman villa by way of Malibu Beach—but it is a statement that has applied across the board throughout his multi-decade career.

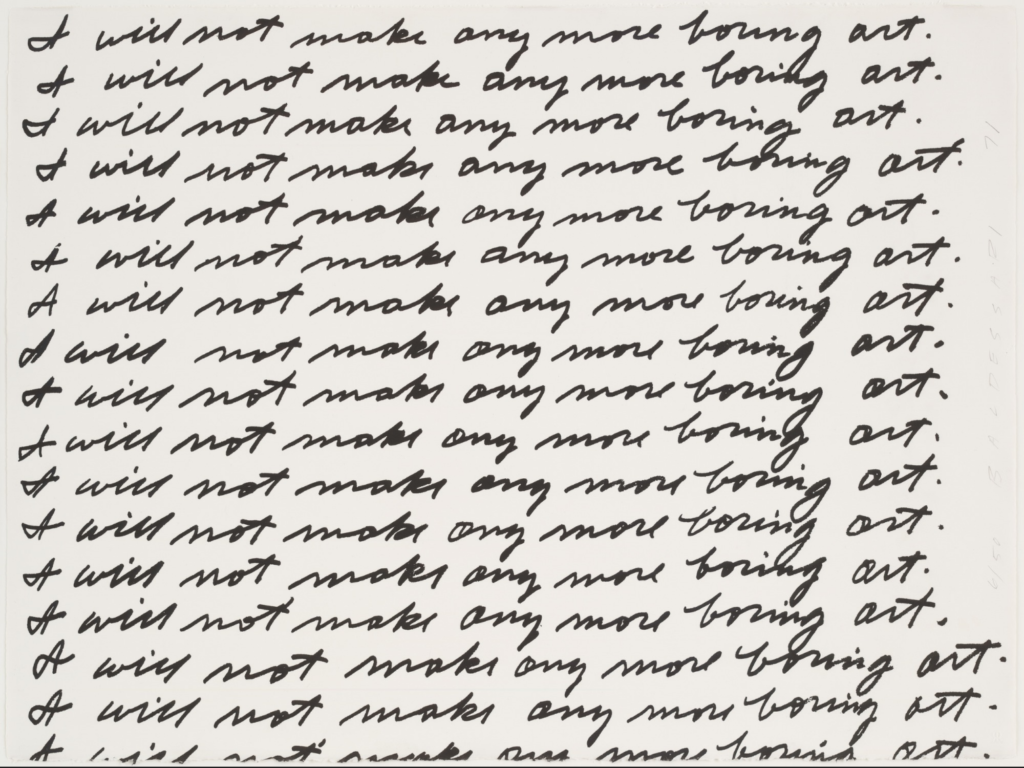

A master of collage and printmaking, he has repeatedly revisited painting and sculpture, as well as exploring photography, books, architecture, exhibition design—even app-making—with just one rule: “No More Boring Art,” a signature phrase of the artist since 1971, as immortalized in a piece in the MoMA collection.

John Baldessari, I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971). Photo courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Baldessari’s work is held by such major institutions as the Hirshhorn, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Broad in Los Angeles, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. He’s been featured in such prestigious exhibitions as the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, the Whitney Biennial in New York, and documenta in Kassel, Germany.

A 1990–92 traveling retrospective appeared at MOCA, Los Angeles; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, in Washington, DC, New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art; and the Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montreal. Another major retrospective, “Pure Beauty,” debuted London’s Tate Modern in 2009, making stops at MACBA in Barcelona, LACMA, and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art over the next two years.

In 2011, Baldessari’s outsized contributions to the Los Angeles art scene were lauded in the Getty Museum’s massive Pacific Standard Time initiative, which saw dozens of Southern California museums mount exhibitions about the consisting of dozens of museum exhibitions that explored Postwar development of contemporary art in the region. No less than 11 of them featured Baldessari, the most of any artist.

As Peter Schjeldahl wrote of the artist in the Village Voice: “Baldessari is a poet of the wrongness that esthetic devotion visits upon flawed, shaggy, mere individuality. He repeatedly evokes the experience, which I believe is quite common, of feeling devalued by what one loves: just not good enough, unworthy, even fraudulent. This is an embittering experience for many. Baldessari absorbs it with consummate humor.” He continued: “Paying attention to his work won’t make you better or happier, but it will remind you what truth tastes like.”