Art World

Friends and Former Students Remember the Late John Baldessari as an Artist Who ‘Always Knew What He Was Doing’

David Salle, Lawrence Weiner, and Martha Rosler look back on their friend and colleague.

David Salle, Lawrence Weiner, and Martha Rosler look back on their friend and colleague.

Zachary Small

Until he died on Thursday at age 88, the artist John Baldessari was engaged in a lifelong battle against good taste.

“Twenty feet back, all paintings look the same,” he said in a 1981 interview, reflecting on his struggle to find a voice after he graduated from art school in 1957. “I couldn’t spend the rest of my life making different combinations of colors.”

So he evolved. In 1970, Baldessari burned more than 100 of his canvases, folding the charred remains into cookie batter and stowing a separate portion inside a book-shaped urn that became a fixture on his studio shelf.

“I’d be busting my ass on a painting and look over at the trash and think that’s much better than what I’m doing.” He would often joke like this, but the artist knew what he had was a breakthrough, writing to curator Marcia Tucker that his Cremation Project was “[his] best work to date.” Years later, Tucker would describe Baldessari’s work as “Pandora’s Box.”

Yet he remained unconvinced that art was his vocation. During his lifetime, he wondered if he should have become a writer, a filmmaker, or a chemist. Friends recall him wanting to become a lay brother, traveling the country in his van to help people. And even later in life, he distrusted the idea that art could change the world.

President Barack Obama presents the 2014 National Medal of Arts to John Baldessari. Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images.

“If I think art should do something, then I shouldn’t be an artist,” he said in a 2007 conversation with the artists Liam Gillick and Lawrence Weiner. “I should be a doctor, curing people.” Asked to look back at his career in 2012, Baldessari said he believed that he would largely be remembered as the guy who put dots over people’s faces.

But Baldessari’s doubts about his work seemed to have no bearing on his role as a teacher in an era in which the conventions of Greenbergian Modernism were flagging. Among his students were David Salle, Meg Cranston, Jim Shaw, Mike Kelley, Jack Goldstein, and many others with whom he remained in contact throughout his life.

“It’s hard to imagine a world without him in it,” artist Martha Rosler told Artnet News over email. She recalled first seeing his text paintings in 1968 at the University of California, San Diego, after driving from New York. “Captions, words busting into silent, canonical spaces—painting, photography—knocked my certainties up side of the head.”

“I will miss John terribly,” Salle said. “I can’t believe he’s gone. I never saw John misplace his sense of humor, even with the demands of his considerable fame. I used to get postcards from him, as I’m sure many others did as well, when he was traveling for shows. I have one sent from Australia just signed ‘Kang-Guru.’”

Despite living in close proximity to Hollywood, Baldessari never settled into his fame as an artist. He was charmingly self-deprecating, telling reporters visiting his Frank Gehry-designed home in Venice, California, to look for the strange building “where the Muppets would live.” He appeared on the The Simpsons as a parody of himself. And he allowed the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to use his text painting, Wrong (1967), as its 404 error page.

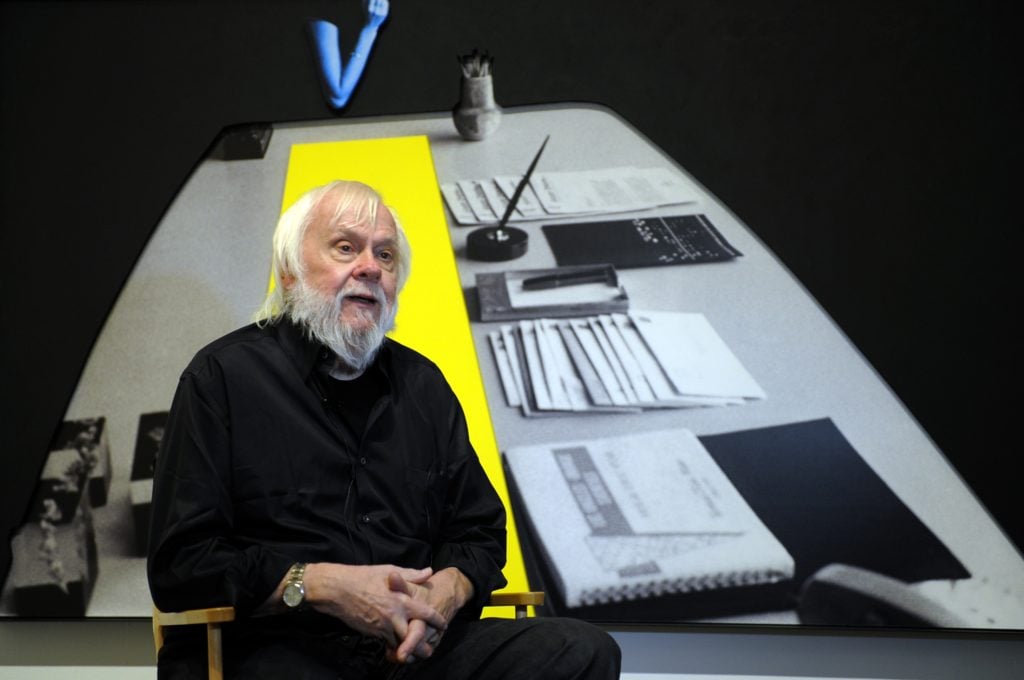

John Baldessari gives an interview at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2010. Photo: Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images.

Among the core tenets of Baldesaari’s work is that learning and conversation involve more than just transforming the space of the canvas; they require a complete reimagining of logical space itself. His incorporation of commercial media and film stills into his work in the 1980s allowed him to explore new dimensions of free association, and to probe the deeper subtleties of absurdity and Surrealism.

The lapsed painter even returned to his brush, covering the faces he saw in photographs with bright dots, lacerating movie stills and filling in the empty spaces with whatever suited him. While New York’s conceptual artists bolstered linguistic and political messages, Baldessari was an overtly emotional artist, a dreamer.

Weiner, the conceptual artist, fondly remembers the many arguments he had with his California counterpart about the function of conceptual art.

“We were friends who didn’t have to agree to disagree,” he told Artnet News. “I’m at a rare loss of words now that John is gone. He was literate. He was witty. He was a curmudgeon. But I remember him always having a list of jokes he had heard.”

“John Baldessari was an artist who always knew what he was doing,” Weiner added.

Baldessari used images the way Goya used language to expose the inadequacy of language, as the art critic Peter Schjedahl observed in a review of the California artist’s series of works devoted to the Spanish painter. I would agree. We have lost our Goya, our court jester, our true north.

“A lot of humor comes out of sadness,” Baldessari once said in an interview, describing the impetus behind some of his work. “I have this idea that civility is just a thin veneer that could crack open any minute. And would it be funny? I don’t know. Yes, it could be funny.”