People

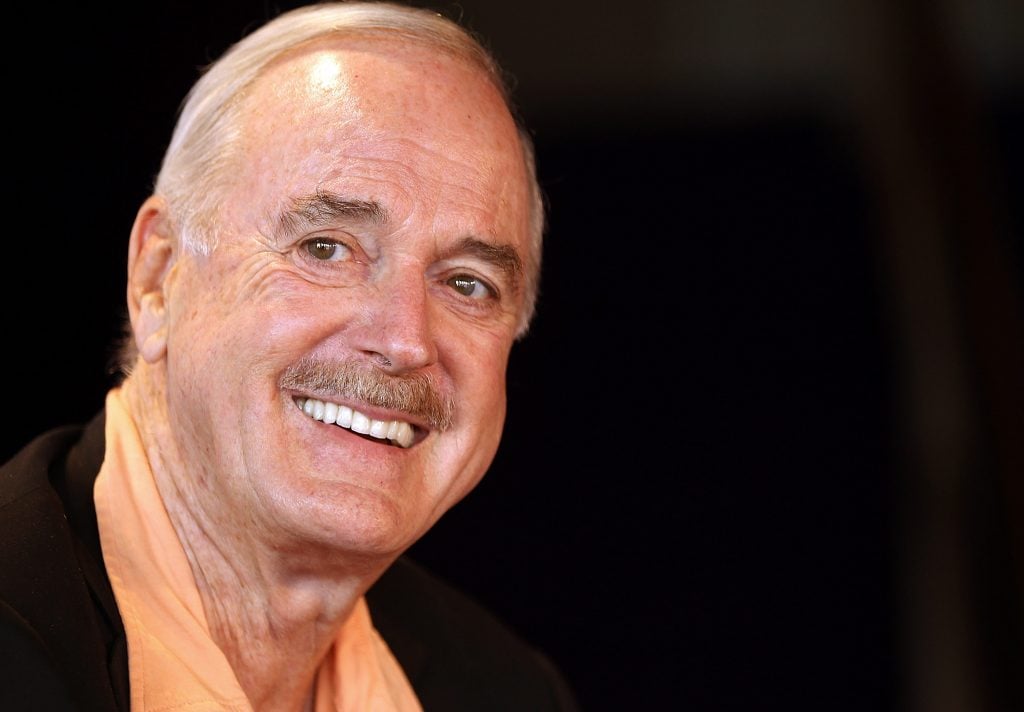

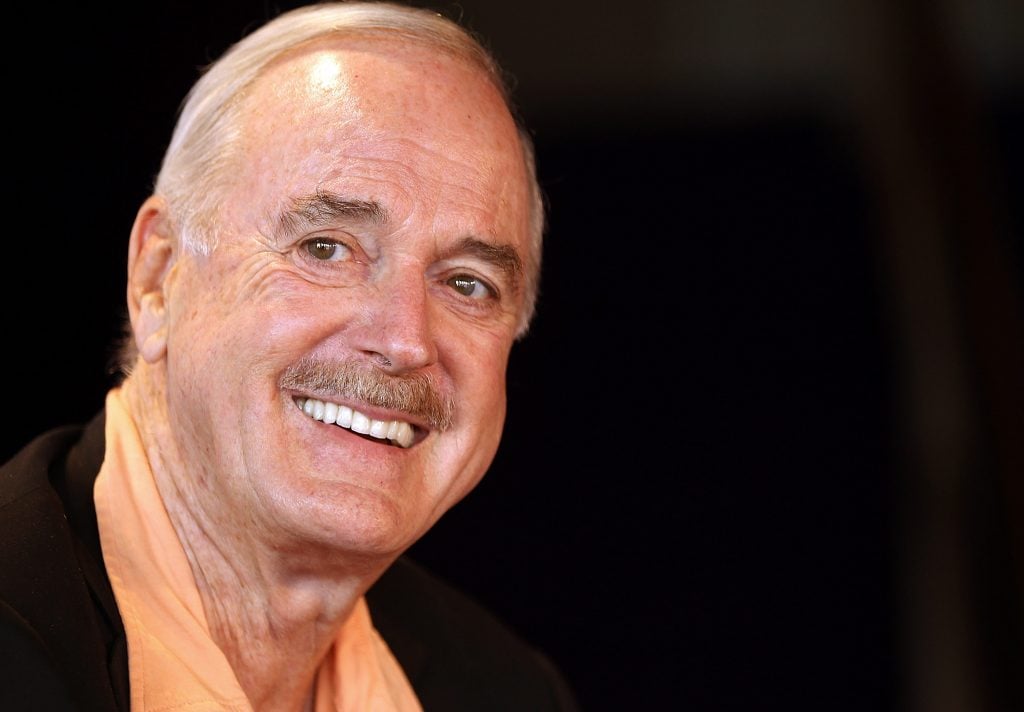

We Asked Comedic Legend John Cleese Why He Decided to Reinvent Himself as an NFT Artist. His Answer Was Rather Silly

Cleese has a bridge in Brooklyn he's willing to sell you.

Cleese has a bridge in Brooklyn he's willing to sell you.

Eileen Kinsella

Comedian John Cleese, who is now a young, anonymous digital artist, is finally (finally!) putting an NFT up for auction.

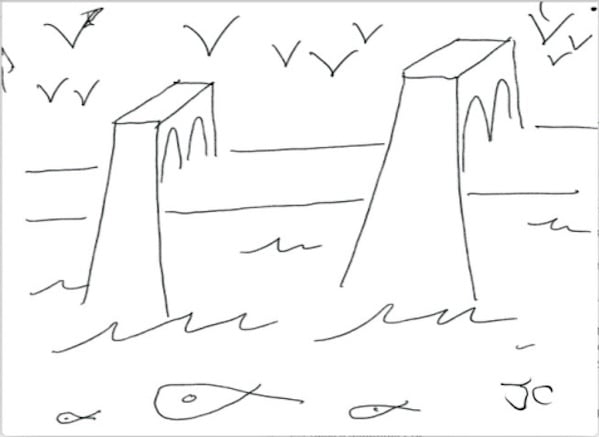

On March 23, Cleese made the announcement via Twitter that he would be selling “a non-refundable token” based on a rudimentary drawing he made of a well-known landmark.

“Today, I’ve got a bridge to sell you,” he said in a live Twitter announcement. “The Brooklyn Bridge.”

Hello! It is time you meet my alter ego "Unnamed Artist" I'm delighted to offer you the opportunity of a lifetime. I'm selling my 1st NFT. Though bidding starts at 100.00, you can “BUY IT NOW” for 69,346,250.50! https://t.co/Vuyx4trvPE pic.twitter.com/aC4oSVfGHF

— The Unnamed Artist (@JohnCleese) March 19, 2021

A bridge? Pray tell, why a bridge?

“A bridge is about trust,” Cleese said in the video. “As in the saying, ‘If you believe that, I’ve got a bridge to sell you.’ When you believe someone, you trust them. And then you buy a bridge from them. It’s that simple.”

Bidding, which began at $100, is now up to a cryptocurrency equivalent of over $38,000 (as of this writing). The reserve price has not yet been met, and—sorry to say—you’ve already missed your opportunity to “Buy It Now” for the very reasonable sum of $69,346,250.50.

Guess when the sale ends? April 1, dummy!

On the occasion of the sale, we spoke with Cleese about NFTs and great art (but unfortunately not about a species of lemur that’s named after him).

What prompted you to create your own NFT?

It came completely out of the blue, on very short notice. I read about the artist who made $69 million and my eyes rolled. Within seven days, a guy with whom I’d worked on animated cartoons got hold of me. He had a brother that worked with me on Third Rock From the Sun, when I had done those shows for John Lithgow.

They said, “We would like you to come down and have you shoot some things, and see if we can give people a bit of a laugh and maybe make a bit of money, because obviously anybody can do this. It doesn’t require artistic skill.”

They just showed me how to draw something digital and said, “That’ll be it.”

What has happened with the bidding on your work so far?

It was at $50,000 at one point and then that bid disappeared, and then people would put in a silly bid for .000001 and that would be registered. And now there’s a $38,000 bid. I’m told it will all happen on the last day, and somebody will think, “I would like to have that.” Probably so they can talk about it at dinner. I don’t understand any of it.

John Cleese, aka The Unnamed Artist, Brooklyn Bridge NFT (2021). Image courtesy the artist.

Do you follow or pay attention to the art world?

I’m one of those people who believes that money spoils everything. You start out with a wonderful gig like basketball and then you finish up with a whole lot of people playing for a city that they have no connection with, halfway on their way to another city that’s going to make them more [money]. That’s professional sport all over the world now. Once money is brought into it, the nature changes.

It’s the same with paintings. Once people are primarily interested in money, any kind of rational behavior goes out of the window. Why does anyone pay so much money for a painting? It’s because it makes them feel special. They don’t look at it and have an emotional experience, at least I don’t think they do. And that’s what I think pictures are all about.

I remember going to The Hague once and seeing a Vermeer exhibition and there was a painting of his very famous view of Delft, and I almost felt my knees collapse. That’s what I love. When I look at a Monet or a Matisse, I just find something in me melts.

I don’t need to put it into words, which is why I don’t particularly like going to art galleries with people. I just want to see what emotional effect it has on me. I think that’s the primary purpose of art.

Do you own or collect art?

I had quite a collection of paintings. I had to sell them after the third divorce. It’s the only real thing I’ve ever wanted. I collected a lot of English watercolors dating from about 1880 to 1920. In particular, a guy called Albert Goodwin, whom I thought just painted the most extraordinarily beautiful scenes. I had a portrait or two, but I was mostly interested in landscapes and townscapes.

So you must have some art market insight as a result?

What I’ve always felt is that anything to do with money is strangely arbitrary. I always thought there was a funny sketch to be written about the very first bankers sitting there in their animal skins saying, “Alright, what’s going to be the token, or the gold standard, of wealth?”

And they say, “Well there’s three runners: there’s gold, there’s zinc, and there’s conch shells.” Everybody laughs at conch shells and then there’s a debate about whether it should be zinc or gold, and they say, “Well, zinc’s very useful, you can use it for lots of things. Gold is no fucking good at all.”

The whole thing is completely arbitrary. And the prices of these paintings are arbitrary. So much of it is that people agree what a value is because they agree what the value is, and that’s what the value is—because they agree.

What’s next? What are your plans if the NFT takes off?

If there is a feeding frenzy and bidding takes off, maybe I’ll buy a little converted farm house in Mallorca, which is my main aim. If this gets a bit of a giggle, then I shall be very satisfied. And if it brings in a bit of money, why not?

I genuinely enjoy making people laugh. In the last few years, when I do tweets and think, “Why am I doing this?” it’s because I love the fact that sometimes I make a good joke and my “twits”—as I call my followers—say, “Thanks for making me laugh.” And that’s enough.