Art & Exhibitions

Police Detained Artist John Sims Without Warning in the Middle of the Night. He’s Taking His Power Back With a New Body of Work

The new series is entitled "A Near Death Residency."

The new series is entitled "A Near Death Residency."

Shirley Ngozi Nwangwa

Last week at around 2 a.m., multidisciplinary artist John C. Sims was awoken by the sound of intruders storming his home.

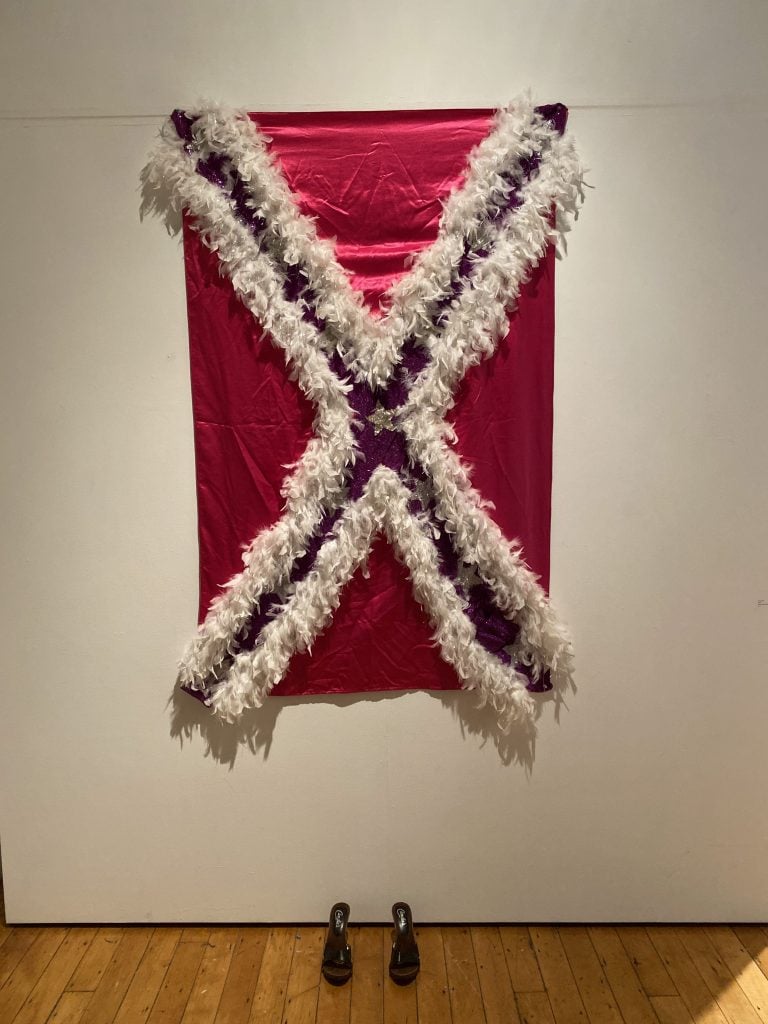

Sims quickly grabbed his phone to call 911, jumping into the bathroom of his apartment, one reserved for the artist in residence at the 701 Center for Contemporary Art in Columbia, South Carolina. Sims’s solo exhibition, “AfroDixia: A Righteous Confiscation,” was in the adjacent building and features deconstructed, distorted, and reimagined presentations of Confederate symbols—including a lynching of the Confederate flag.

As an artist showing a body of work in the South centered on a critique of revisionist historical materials, Sims immediately feared that “some white supremacist mob or the KKK had come for my life,” he told me over Zoom this week. “I didn’t want to disappear in some underground torture chamber.”

When the intruders revealed themselves to be cops, Sims had to switch fear gears. He was taken back to his mother’s and every Black mother’s survival lesson. He prayed that the clanky radiator wouldn’t echo loudly enough to suggest that he had a gun.

Exhibition view, John Sims’s “AfroDixia: A Righteous Confiscation” at the 701 Center for Contemporary Art. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

After multiple pleas for an explanation, and multiple attempts to identify himself as the artist in residence, he was seized, handcuffed, and detained for nearly eight minutes. “Why are you here?” one officer asked.

For Sims, this question was particularly gutting. “Black people are always in a defensive stance when we want to take up space. ‘Why are you here?’ they ask you. ‘What gives YOU license to do and say what you do?’”

After the police ran his license, confirmed he was in fact the artist in residence, and released him from handcuffs, he felt the pendulum swing in his favor. He was lucky to be alive when the alternative could have been a death marred by a media narrative suggesting he had asked for trouble by staging a show disrespecting the Confederate flag in South Carolina.

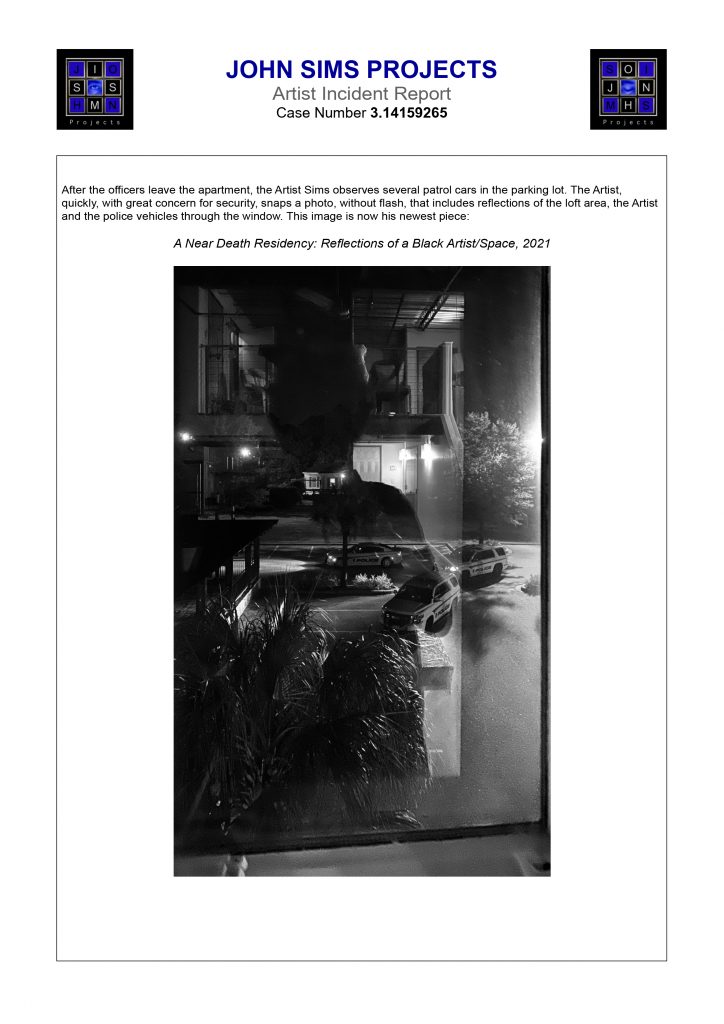

Before the police drove off, he took a picture of their squad cars through the window. Immediately, he felt called to tap into his creative self—time was of the essence. He needed to translate his experience into art in order to stake a claim to the narrative before his voice got drowned out.

John Sims, A Near Death Residency: Reflections of a Black Artist/Space (2021). © John Sims

The result is a new body of work that has already begun to take shape under the title “A Near Death Residency: Reflections of a Black Artist/Space, 2021.” So far, it consists of two parts: the only photo he was allowed to take as documentation of what happened on May 17, 2021, and an Artist Report he drafted in response to the police’s official incident report. This account will also provide the basis for a future film, a dramatic reenactment meant to turn the villainizing crime-show format on its head.

Sims’s booming laughter rang through my speakers as we spoke. “The police may beat my ass, but once I’m robbed of the opportunity to tell my story, my trauma of how they beat my ass?” he said. “If you squash people at that level, you don’t have a democracy. You can’t have a democracy. If people don’t have the space to express their own voice, that is evidence of the American sham.”

***

The police department’s press release recounted a “police-citizen encounter” in which officers “noted an open door at the side of a building which is normally locked.” They entered with firearms drawn, the release stated, and “repeatedly identified themselves” as they pursued footsteps on the second floor of the building, where they placed “the man…in handcuffs to determine why he was in the building.”

Sims’s answer to the police’s statement, which he drafted hours after the intrusion, reclaims his personhood and respect by replacing the sanitized label of “citizen” with Artist Sims. “I mimic the energy” of the original report, he explained. “I’m saying, ‘You will respect me.’”

The document is styled like the one released by the authorities, with his “John Sims Projects” artist logo in place of the Columbia police department’s emblem and a case number of 3.14159265 (pi out to eight decimal points), a figure that Sims has been using in his art for years.

In the official incident report, the Columbia police chief referred to the refusal of the supervising officer to allow Sims to take a photograph of the cops in his home as “the only misstep” committed by law enforcement that night. Sims is determined to transform the police department’s reductive statement of “accountability” into an indelible body of work.

The artist sees a clear line between his show, “AfroDixia,” which is about remixing artifacts of the Confederacy, and his new series, which comes out of a desire to drain law enforcement, which he calls the “cousins” of the KKK, of their power to intimidate, smear, and subjugate Black folks, stripping them of agency.

John Sims, A Group Hanging. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

“I’m sure there are plenty of people who thought I’d shut up and just be an artist,” Sims said. Instead, he plans to start work on the next chapter: a film that brings together what happened to him, the significance of his art, and the precarious nature of his life as a Black artist.

“The writing paints the pictures and brings the bullets,” he said. “The film will create heat and drama around the boundaries of our sense of respect and respectability.”

***

The anniversary of George Floyd’s death has come and gone, along with calls for community reconciliation after John Sims’s encounter with police. Since the incident, the 701 Center has invited the Columbia city mayor, police chief, and city council members to Sims’s “AfroDixia,” which now radiates with heightened significance.

In a statement released on May 28, the 701 Center noted that “this was not the first occasion in which a resident of… the 701 Whaley Street building encountered a law enforcement officer searching the premises for a possible intruder.” But it was the first time, the statement noted, that “such an encounter led to hostile confrontation, detention, cuffing, and a records check.”

While previous encounters “resulted in courteous apologies from officers,” there was a key difference: “Mr. Sims is a Black man; the other incidents involved a white man.”

John Sims, Drag Flag. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Earlier this week, while showing the mayor, a Black man, Stephen K. Benjamin, around the gallery space, Sims was assured that he would be able to address the city council directly on Tuesday, June 1.

At the meeting, Sims will read his Artist Report to both the city council and representatives from community organizations who have pledged their support, including Black Lives Matter South Carolina and the National Action Network.

The reading will serve as the next phase of the “Near Death Residency” project, continuing the act of blending art with life, an artistic foray that Sims says was brought about by the cosmic combination of “AfroDixia,” his residency, the Southern city with its cotton-mill grounds, and the police—all players in a production for which life set the stage.

“I couldn’t have planned this,” he said. “The experience is now part of the work.”

Read Sims’s Artist Report in full below.