People

‘When I See These Paintings, I See Myself’: Artist Jordan Casteel on How She Puts Herself Into Her Celebrated Portraits of Everyday People

The painter says the real joy of her work is showing her portraits to her subjects.

The painter says the real joy of her work is showing her portraits to her subjects.

Taylor Dafoe

Jordan Casteel has followed a trajectory few artist can relate to.

This week, she opened an impressive institutional show at the New Museum in New York titled “Within Reach,” and her paintings are selling for six figures at Christie’s. A giant portrait of hers now looms over New York’s High Line Park, and she’s quickly become a poster child for new figurative painting.

But Casteel, with her signature pixie cut and cat eyeglasses, has always been a step out of sync with the rhythms of the art world.

At 23, she got into Yale’s renowned art school after Googling “best MFA programs.” The year she graduated, she opened “Visible Man,” a buzzy debut of intimate portraits of naked men at Sargent’s Daughters.

“I’ve always been interested in trying to capture the people behind the scenes,” Casteel tells Artnet News. Her work, like the offspring of Alice Neel and Kerry James Marshall, makes you feel both intimately familiar with her subjects and like you’re seeing them for the first time.

On the occasion of her New Museum show, we visited the artist’s studio in the Bronx, where the walls are hung with candid photos of subway riders and others source materials for future paintings.

Details from Jordan Casteel’s studio, 2020. Photo: David Schulze.

I want to start by going back to your time at Yale. I heard that when you first went there, you showed up with a couple of prestretched canvases from Michaels art supply and an easel from Hobby Lobby. That’s a far cry from where you are now.

It’s true. [Laughs] When I got to Yale, that was the first time I had a traditional “studio.” I had been painting out of a second bedroom up until that point while I was teaching special education. I was using it as a space of relief, as a space of relaxation after stressful teaching days. When I applied to graduate school, I knew it was going to be an opportunity where I could indulge in a studio practice. And having a space where I could close the door and be by myself is what Yale offered. It was quite magical.

I literally knew nothing about anything. I had three paintbrushes from Michaels. I was buying Dick Blick or whatever brand of paints that were the cheapest. I didn’t know about color theory or mixing or about brushes. In my first year of graduate school, I was just trying to pick up technical bits and pieces from my classmates wherever I could, because I realized quickly that I wouldn’t be taking a painting class in the way that I thought. Like, in my head I was going to art school, which meant that somebody would teach me how to paint.

Details from Jordan Casteel’s studio, 2020. Photo: David Schulze.

You would walk into a room with a naked model and a bowl of fruit in the middle of it.

Exactly! It would be old school. I’d be at my easel that I brought with me, living my painterly dreams. On the first day of registration, I was sitting next to the faculty member who was advising me and I said, “So I’m really interested in signing up for a painting class. Where do I do that?” And he was like, “Uh, we assume that if you’re here, you’ve already done that.” I was like, “Oh, yeah. I mean, of course. Been there, done that.” [Laughs]

I realized quickly that I needed to be a learner first and foremost, to ask a lot of questions and be shameless if there were gaps in my knowledge base. I genuinely believe that it was this deeply embedded curiosity that ultimately became the sustaining force during my graduate degree. It was a difficult time.

Jordan Casteel, 2020. Photo: David Schulze.

Did you always have that sense of curiosity growing up?

Growing up, I was very awkward and kept to myself. At the same time, I guess I was sort of cool. I played sports and was often the captain because I made other people feel good. I’m a people person to a degree, so I took on a lot of leadership roles in high school. I was the president of the black student association, and I designed T-shirts. In field hockey, I would make all the ribbons. But all of that is to say I ended up my junior year in a drawing class on accident. There was a gap in my schedule and I didn’t actually sign up for it.

It was like The Breakfast Club. It was all the weirdos that ended up in this art class and didn’t want to be there and I would just hang out with the football players in the corner. But I actually kind of enjoyed it. I started this sketchbook, and I would do tattoo drawings for people. I had this hustle, this little business where somebody would give me their family picture, and I would draw it and give it to them for $20 bucks or whatever. Someone along the way was like, “Oh, you’re kind of good.” I had no idea. So I just kept it up, but I had no real connection to art in Denver. What we understand as the art world, that meant nothing to me.

I took art classes in college, but my major wasn’t studio art until my junior year, when I studied abroad in Italy and took my first painting class. It was kind of like, “Here’s a palette knife. Make some colors and throw it on there. Drink cappuccinos and have the wind blowing in your hair. Paint portraits or whatever you want.” And I did. I painted portraits of a lot of the grounds-keeping staff, which isn’t far from my practice as it stands right now. I was very interested in trying to capture the people behind the scenes. Those were the relationships that I found to be the most intimate and important to me.

When I got back, I changed my major to studio art. My parents were not particularly happy about it. I finished undergrad and ended up teaching, which I’ve always loved. I was painting my students when I applied to Yale.

Details from Jordan Casteel’s studio, 2020. Photo: David Schulze.

Do you feel like that lack of traditional background shapes the way you make work today?

I definitely do. I think that my practice has benefited from the naiveté that I went to Yale with. Unlike my peers, who were trying to unlearn all the traditional methods they had been taught, I came in as myself. I was all over the place, but all I needed to do was focus in and tighten up my skills. I think that’s allowed a freshness in the work and an uninhibited way of making.

There is a lot of entitlement in art school and in the art world, where people feel they’re deserving and owed something at every beck and turn. I didn’t have that because I knew I was an anomaly. I was just waiting for somebody to tap me on the shoulder and say, “Actually we made a mistake. We don’t know why you’re here. Get going.” I felt that every opportunity I was getting was possibly the last, so I made the most of each one. I have an ego, because I think every artist has an ego—you have to have an ego if you think you can sit alone all day and spend your time exercising your own ideas on a canvas—but I try not to take anything for granted.

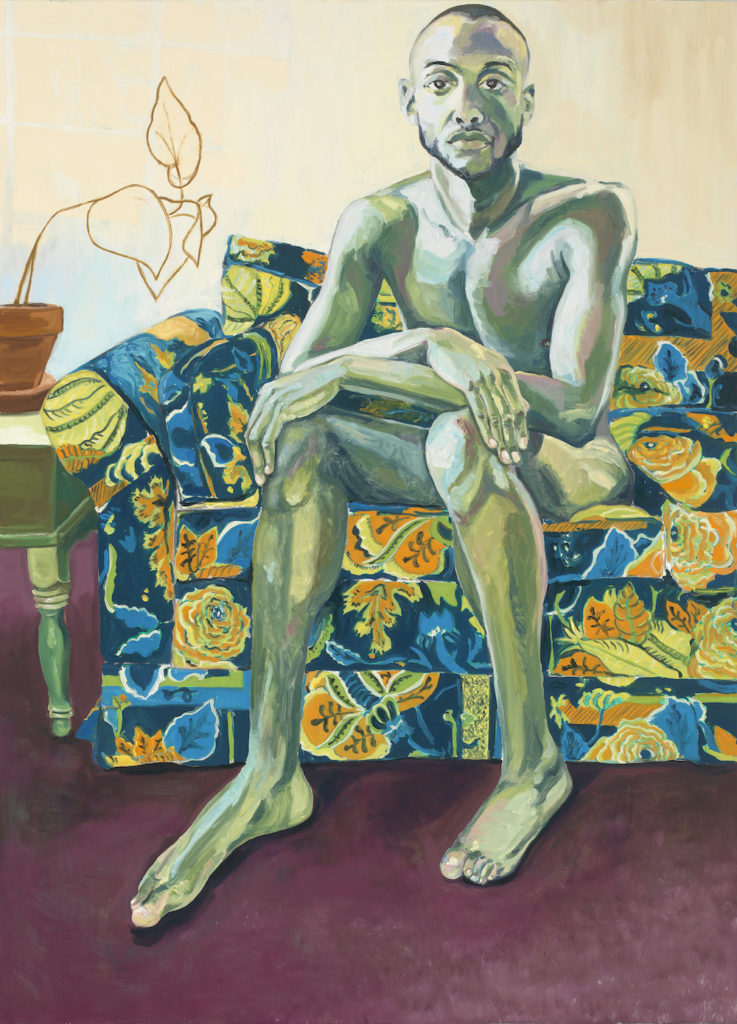

Jordan Casteel, Jireh (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York.

Then you moved to New York after graduation?

Yeah, everybody was graduating and going to New York or LA. I figured I should follow suit. If I had committed to that much, then I should try a little bit further. I came to New York because of my family connections—my mom’s sister still lives on the Upper West Side. I was being very strategic in the sense that if I end up broke and without a house, I would at least have a place to stay and a family member who would feed me. So it was like a backup plan. I’m really keen on backup plans.

It was a struggle when I first got here, trying to figure out what a studio would look like, but I found a 200-square-foot space in Bushwick for $400 a month. I got that place right after I found out I was going to have my first show at Sargent’s Daughters, where I showed the “Visible Man” series. At that point I was like, “I’m going to try to do this thing. I’m going to be an artist.”

Details from Jordan Casteel’s studio, 2020. Photo: David Schulze.

With that series, and the one that followed it the next year at Sargent’s Daughters, Brothers, much was made of the fact that you were only painting men. It’s strange, looking back on it. Why do you think that was such a hang-up for some people?

I love that you felt that, because I felt that way too. I’ve found throughout my young practice that people find ways of accessing the work through things they understand. They’ll find language or concepts that feel tangible and sink their teeth into them, then never let go. For some, it’s what my gender is or what the genders of my sitters are.

The idea of me as an African American woman painting African American men or bodies in general—people want to use that as the anchor on which the work rests. It’s as if they were like, “Okay, it’s black. It’s men. They’re naked. We’re done. We’ve understood it.” Those weren’t the center points for me in developing and thinking about that work. They are truths, they are facts of being that I can’t ignore, and of course I considered them when I was making the work. But it was not the source for which the greatest amount of significance came from for me. For me, it was about something more.

Details from Jordan Casteel’s studio, 2020. Photo: David Schulze.

It’s also not a critique you would hear lobbed at a male artist painting women.

Of course not. That hasn’t been the case throughout history, especially when it comes to white men throughout history.

I remember doing a talk at the Studio Museum with Kerry James Marshall, EJ Hill, and Kevin Beasley. I was just trying to keep my life together, because, you know, I was on stage with Kerry James Marshall, living my dream of all dreams. And at the end, during the Q&A, a woman raised her hand and asked me why I was only painting men. “I think that you should be painting women,” she said. “It doesn’t make sense to me why you’re denying women the opportunity to be seen. All voices need to matter, too.”

She said that to me while I was on this panel, the only woman sitting up there. And I was like, what you’re doing right now is reducing me as a woman making these paintings and reducing my presence within them. You’re ignoring the fact that I have labored over this work myself and that it has been translated through my being as somebody who identifies as a woman, through a very specific feminine lens. When I see these paintings, I see myself, which means that the woman or the feminine is present in every painting that I’ve ever made, whoever is represented within them.

We have to think bigger. If you’re actually taking the time to see me in the way that I’m trying to see these subjects and the things that I’m looking at, then I think that you would discover that there’s a lot more complexity involved. So yeah, the narrative of “Jordan Casteel paints black men” tired on me really quickly because it just didn’t feel right. It didn’t feel true.

Jordan Casteel, Within Reach (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York.

Recently you’ve been painting your students at Rutgers, where you teach. It hearkens back to the portraits you were making when you applied to Yale. What is it about certain communities that interests you?

For me, it’s about coming out of oneself. Because the ego is so deeply embedded in an individual studio practice, it’s important for me to leave my own space of making and live in the space of others. Their learning and curiosity inspires my desire to continue to learn and be curious as well. At Rutgers, I start the semester by saying I probably know less than they do, which is true in many ways. Most of my students are coming into my class with more training than I had when I started at Yale. And I still don’t know a lot of things, but I do think that I can offer a lot of support in terms of mentorship, guidance, and filling in the gaps of their knowledge about the art world or what it looks and feels like to manage one’s time with intention in ways that I think are important.

I genuinely believe in the notion of there being a difference between symbols, which artists tend to traffic in, and substance. It’s one thing to say that I care a lot about people, and it’s another thing to really be involved in people’s lives meaningfully. So I try to exercise that where I can and however I can, and education has been the form in which it has worked most seamlessly in my life and I have felt most of service to others. I debuted this body of work at Casey Kaplan in New York this past November.

Details from Jordan Casteel’s studio, 2020. Photo: David Schulze.

Do you think it’s possible for a full-time artist to straddle both those categories, substance and symbol?

Of course, because I think there are many ways to exercise one’s substantive work. And what that looks like and feels like is different to everyone. For me, it requires the physical labor of stepping outside of my space and into the space of someone else. The work does a lot, but my physical body needs to be doing more. That’s just my own personal solution.

I love the pictures and videos on your Instagram of your painting subjects seeing their portraits in person for the first time. What do those moments mean to you?

Talking about this makes me almost speechless. It’s where I become the most emotional and uncertain of my words. When somebody sees their painting the first time—those are the moments that remind me the most, out of everything in my practice, why it is that I do what I do. It reminds me of the importance of the work and how it’s bigger than me sitting alone in a studio making paintings, or paying my rent, or whatever kind of concerns I have in my life. Those things become really irrelevant in the moments in which people are seeing themselves portrayed on such a monumental scale in such historical and significant spaces.

For example, James, whom I’ve painted a couple of times, the first time he saw his painting, he ran out and got his wife. Later, she was asking around where the artist was, and somebody pointed me out. Then she ran up to me and threw her arms around me and said thank you. She said, “Thank you for seeing the man that I love the way that I have always known, as beautiful as I have always seen him to be, as I have always known him and as wonderful as he is, and then sharing that with the world. I’ve always wanted him to be seen as I see him, and you’ve done that.”

I think that that is bigger than anything else I’ve done in my life—putting people, who have maybe spent their lives feeling invisible in certain ways, front and center and honored in the way that they ultimately deserve to be honored.

“Jordan Casteel: Within Reach” is on view now through May 24 at the New Museum in New York.